A Primer on IP/IPv6 Mobility

June 27, 2011 in Systems10 minutes

At the end of my Senior Design sequence, a professor asked if I had time to look into IPv6 Mobility. At the time, I had to tell him no, since it was considered to be out of scope for the project. It’s a shame really - the concept of IP Mobility in general is extremely fascinating.

I’d like to point out that IP Mobility is well-documented technology - and I’d rather not spend a lot of time explaining it, since I’m sure there are articles out there that do a much better job. I will, however, explain it on a relatively high level, but only because I will then identify some potential use cases so you know when it’s a valuable tool to get out of your arsenal, and then explore what’s new about IPv6 that improves the way mobility works.

In this post, we’ll answer the following questions:

- What is IP Mobility?

- Why use IP Mobility?

- What’s new about Mobility in IPv6?

- How can I play with it?

What is IP Mobility?

The primary goal of mobility as it applies to IP networking is to allow a device to keep the same IP address regardless of the network the device is connected to. This could be useful especially for devices that are intended to be mobile, such as smart phones, tablets, and laptops, but also for other devices.

The concept of IP Mobility allows for seamless connectivity using the same address. In certain applications like VoIP and VPN, sudden changes in network connectivity or network address can cause problems. IP Mobility helps to alleviate that problem by allowing the device to keep the same IP address.

That sounds pretty cool. So how is this accomplished?

First, we need to de-acronym a few things. You’ll see most of these pop up a lot in any sort of IP Mobility document:

- MN - Mobile Node

- HA - Home Agent

- FA - Foreign Agent

- CoA - Care-of Address

We’ll define these terms as we go along.

The best analogy to consider when trying to understand IP Mobility is VPN. In a VPN, you have a physical address that actually provides your device with connectivity to the local network. When forming a VPN, a tunnel is established between the remote network and a virtual interface on your device. This gives your device two addresses - one that’s meaningful to the remote network, and one that’s meaningful to the local network. Typically in a VPN scenario, all traffic is routed first through the virtual interface, which is configured with a secure tunnel that uses the device’s physical interface to connect to the remote network.

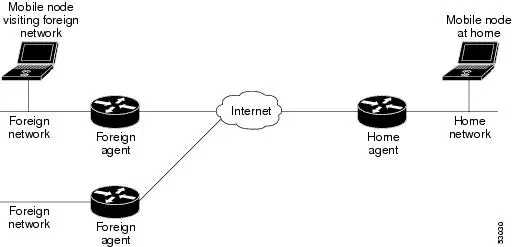

IP Mobility is very similar. A Mobile Node is the mobile device itself - the network-attached device that is “away” from it’s home network. When the MN is on it’s home network - that is, the network that contains the address the MN is trying to keep - it communicates with its Home Agent, which is usually a router of some kind, to let it know that it is “home”.

When the MN leaves the home network, and connects to some remote network, it initiates a process that updates it’s location to the HA and enables traffic to be sent to it. This is done in three phases:

**Agent Discovery **- Home Agents and Foreign Agents (usually the router on the remote network) send out advertisements periodically on the link for which they provide service. MNs can send solicitations on these links to see if any of these agents are available.

Registration - When the MN detects that it is attached to a network that is not it’s home network, it registers it’s Care-of Address, which is the address that identifies the device on the remote network, with the HA, so that the HA knows where the MN is located, and as a result, where to send traffic. The RFC for IP Mobility points out that this registration can be done either directly to the HA, or through the FA, which will in turn forward the registration to the HA. The RFC also notes that the CoA can be obtained through advertisements from the remote network, or through other mechanisms like DHCP. When the MN moves from remote network to remote network, a de-registration request is sent, and a new registration request follows. When the MN connects back to it’s home network, a de-registration request is sent, and traffic operates normally.

Tunneling - Datagrams sent to the MN’s home address are intercepted by the Home Agent, and tunneled either directly to the MN, or to the Foreign Agent, which will in turn deliver them to the MN. The MN is configured to reply to these packets via the same tunnel, so that all traffic to/from the MN behaves just as if the MN was on it’s home network.

As you can see, this is a relatively complex process, but one that allows a device to roam, and allow communication using the same address from network to network.

Why use IP Mobility?

I know I struggled with this before the bulk of my research, and I have a feeling that you are too - why use IP Mobility? Why would someone really care that they have the same IP address as they move from network to network?

Well, the big use case for IP Mobility is the typical mobile devices like smart phones. With the rise in demand for mobile access to the internet, an even higher level of importance has been placed on having a seamless ability to roam using the same connection. From a network access perspective, this is as simple as moving from one cell tower to another. However, there are underlying implications to consider. For instance - whose tower are you now connected to? Does that company also own the same tower you just moved from? (See PSDN) Because of these questions, it is impossible to maintain state with applications like voice, or many others, if a device is moving around geographically like this. As a result, mobility is used within a carrier to ensure that communication to the same device located at the same IP address can remain constant.

The screenshot above is on an Android device showing both the device’s IP address, as well as it’s “external” address. That 172.16.0.xxx address is likely to be a mobile address, or in other words, the address that stays with the device no matter what. If you’re familiar with RFC 1918 (as all networkers should be), you’ll notice that this address comes from private address space. My analogy of a VPN is even more accurate in this way because this address is private, and is only meaningful on the private network of whatever carrier serves this device. When connections are made to this device, they go first through the carrier’s network, where they would have a home agent set up to intercept that communication and route traffic along the ip mobility tunnel to the device.

The public internet address shown, which is 87.122.118.xxx, is simply the address visible to others on the internet that the mobile device connects to. This address would belong to the carrier in this particular case and since the MN’s address is private, it would come out of an address pool used for NAT.

Other use cases exist for IP Mobility; as more and more organizations manage their mobile device connections, or simply more workers are using mobile devices, it is important to maintain consistency with addressing on the mobile devices, depending on the applications that they’re used for. Even inside an organization’s private network, an increasing number of companies are employing Mobile IP solutions to manage mobile connectivity.

What’s new about Mobility in IPv6?

IPv6 Mobility, also known as Mobile IPv6, or just MIPv6, is what we call this technology when used over IPv6. As you’ve seen, IP Mobility isn’t new to IPv6, (RFC 3344) it was just difficult to manage with disruptive mechanisms like Network Address Translation.

There is two big differences between IPv4 and IPv6 with respect to Mobile IP. First, Mobile IPv6 does not have the concept of a foreign agent. If you recall, in the Mobile IPv4 architecture, MIP tunnels could terminate either directly to the Foreign Agent or to the mobile device itself. The reason this choice was given is to allow for a workaround in the presence of NAT. The tunnel could terminate to the NAT device, which would then function as a foreign agent, and send traffic along to the mobile device. Since Mobile IP tunnel encapsulation can take a variety of forms, like “IP in IP” or GRE, each with it’s own level of compatibility with NAT, this provides network administrators with some options to cater the mobile IP solution to their network design. However, in IPv6 there’s no need for NAT, so tunnels can terminate directly to the mobile device. As long as the firewall configuration permits the tunneling protocol, the home agent can send traffic directly to the mobile device itself.

The second key difference between MIPv4 andMIPv6 is the update to the “Destination Options” extension header. This header contains the necessary information to get the packet to the mobile endpoint. This new feature means that Mobile IPv6 does not require tunnels because this extension header makes Mobile IP an optional yet integral component of the IPv6 protocol itself. As a result, there’s far less overhead. When the packet arrives at the home network, the Home Agent adds the necessary mobility options (A tunnel would require at least an additional IP header) and forwards the packet on to the mobile node.

In addition, there are more new features in the IPv6 protocol itself to support Mobile IP. Since mobility support is a standard feature of IPv6, it is expected that every IPv6 node can support Mobile IP.

- The Neighbor Discovery Protocol has been changed to add new options for Mobile IP.

- The “Destination Options” extension header has had a new option added for Home Address.

- Additional ICMPv6 messages have been added for home prefix and home agent discovery.

- Mobility messages have been updated to include a new set of mobility options

- A new Type 2 Routing Header has been added

As you can see, this particular technology, like many others (i.e. IPSec) was given careful consideration when designing IPv6 - yet another reason why IPv6 isn’t just the new protocol, but a true improvement and a successor to IPv4.

How can I play with it?

Cisco’s implementation seems to be the most well-documented way of turning up your own mobile ip solution. They have configuration guides for IPv4 as well as for IPv6, which will allow you to set up a Home Agent that your mobile nodes can register to.

In addition to setting up a functional home agent, you’ll also need to configure your mobile nodes properly to participate in the Mobile IP design. At one time, Cisco had a Mobile IP client, but that product was discontinued. As of today, in order to configure mobile endpoints to participate in Mobile IP, your best bet will be to stick with third party or open source software packages that act as mobile IP clients. A walkthrough for configuring Mobile IP on IPv4 using VTUN is located here. A walkthrough on configuring Mobile IPv6 on Linux can be found here. (If you can sort through all the “windows mobile” stuff, I’m sure a similar solution exists for Windows)

Seeing how easy this is to configure, especially in IPv6, I’m adding this to the list of things I’d like to try out. Maybe sometime in the future I’ll make a post about my configuration steps and some packet captures (You know you want to see them) of a successful implementation.

References

- Mobile IPv6 - http://www1.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/cse574-08/ftp/j_imip62.pdf

- IPv6 Mobility - http://ww.6diss.org/workshops/saf/mobility.pdf

- IP Mobility Ensures Seamless Roaming - http://www.eetimes.com/design/communications-design/4137995/IP-Mobility-Ensures-Seamless-Roaming/

- Introduction to Mobile IP - http://www.cisco.com/en/US/docs/ios/solutions_docs/mobile_ip/mobil_ip.html

- Mobile IP - Changes in IPv6 for Mobile IPv6 - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mobile_IP#Changes_in_IPv6_for_Mobile_IPv6

- IP Mobility Support for IPv4 - http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc3344.txt

- Mobility Support in IPv6 - http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc3775.txt