Introduction to OpenFlow

June 15, 2011 in Systems6 minutes

Ah - I can finally breathe a sigh of relief, for I am finally done with my Senior Design sequence, as well as my undergraduate education. I’ve been feeling a little out of place, actually, since I’ve been in research mode for the last 9 months for my IPv6 project. So, after a short break, I decided to get back into things that I was just getting started with before all of that started.

Fortunately, one of the things I’ve been watching in the networking world has seemed to grow even more mature with age since I’ve been paying exclusive attention to IPv6. I’m talking about OpenFlow. In this, the first of a multipart series on OpenFlow, we’ll talk on a relatively high level about this new concept, then we’ll move into some of the more pressing questions you may have regarding it’s technical function, as well as go over some of the debates surrounding OpenFlow. In this post, we’ll answer the following questions.

- What is OpenFlow?

- What are the advantagesdisadvantages of running OpenFlow?

- How can I play with it? (What equipment uses OpenFlow?)

What is OpenFlow?

OpenFlow is a big buzzword in the routing and switching research and development shops these days. According to the OpenFlow website, OpenFlow is:

…an open standard that enables researchers to run experimental protocols in the campus networks we use every day.

Okay so that’s nice. But how?

In order to appreciate the concept of OpenFlow, one must think of how routers and switches operate. Typically, the fast packet forwarding, known as the data path, and the decision-making process of switching or routing, which occurs within the device at a higher level, occur on the same device. In the case of a switch for instance, each port is configured to send and receive bits at line rate, and perform tasks that were determined by the “brain” of the device, which is where higher-level decisions are made.

OpenFlow defines a standard upon which these two concepts can be abstracted. This means that these two functions no longer have to occur on the same device. This results in the useful ability to define your own rules on the control plane, rather than relying on some algorithm that someone else built - you could write your own control protocol to define where packets go and why, specific to your needs.

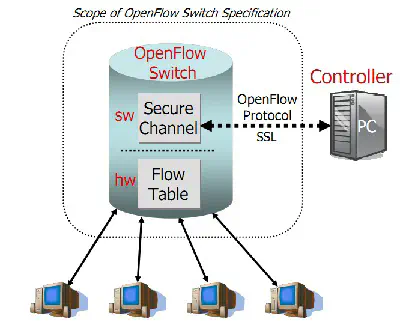

Since the control plane has been separated from the data path, it becomes possible for network researchers to develop their own algorithms to control data flows and packets. When switches or routers that use an OpenFlow server receive a packet that it doesn’t know how to handle, it contacts the OpenFlow server. This server responds using the OpenFlow protocol, which directs the device according to how the network engineer has programmed it. The diagram shown below, taken from the OpenFlow whitepaper, does a really good job of visualizing this:

Copyright © Open Networking Foundation 2011.

Copyright © Open Networking Foundation 2011.

When it’s all said and done, OpenFlow presents us with a new and easy way of making “programmable networks” a present-day reality.

OpenFlow Pros/Cons

First, this is an obvious leap forward for network researchers. Without this, in order to run experimental network protocols, network researchers either had to work with a vendor to allow “under the hood” work on their platform (which was often met with a resounding “no”) or they had to build their own equipment out of regular PC hardware, and an OS like Linux. Many networks employ PCs to perform network functions in the same way typical high-end Cisco, HP, Brocade, etc. equipment would.

However, a PC is a PC, and it will never have the kind of performance or scale that a product that’s designed for network infrastructure will. A PC can neither support the number of ports needed, nor the packet-processing performance (wiring closet switches process over 100Gb/s of data, whereas a typical PC struggles to exceed 1Gb/s - and the gap between the two is widening).(ONF)

Those that enjoy taking the risk associated with trying out new things, as well as users with special requirements that make the use of a custom OpenFlow protocol a necessity would also be eager users of this technology.

A lot of folks prematurely dismiss OpenFlow because they don’t see a need to run it in their networks - and for the most part, they’re right. Right now, OpenFlow is primarily in use for network R&D to actually define some of these custom control mechanisms, or for customers that have seen the work done on the OpenFlow platform, and perhaps wanted to use something that had been developed. OpenFlow will continue to grow in popularity as people realize the scope of what is truly a sudden change in fundamental network concepts, and as a result, be able to come up with innovative ways to improve the function of the network. OpenFlow shouldn’t be dismissed just because it’s not very useful on one particular network at one particular point in time.

An obvious disadvantage of OpenFlow is it’s youth. The current version (1.1.0) was released February of 2011. As with all technologies, new ideas that haven’t gone through a trial by fire tend to be buggier than the more mature technologies out there. This is why it is not recommended to run OpenFlow “just because”. OpenFlow is not for users or organizations that have standard network requirements, and wish to invest money in a product that works out of the box. Those users will be just fine with name brand networking equipment.

How can I play with it? (What equipment uses OpenFlow?)

As stated before, OpenFlow is a new technology, so one of the biggest “cons” right now is that it simply hasn’t penetrated the market very much just yet. According to seekingalpha.com, Marvell (a founding member of the Open Network Foundation) is starting to produce switches that support production-level OpenFlow.

My thoughts? It’s going to stay this way for a while. If you think about it, this is a HUGE change in the way we run networks. The biggest effect this will have, by a long shot, is the way we use existing networking technologies from big names like Cisco. Open technologies like OpenFlow which allows some third party or even the organizations themselves to define rules for the way the network should perform, would be a serious competitor to these networking giants. As a result, most major equipment providers will either be hesitant to implement OpenFlow, or completely against it. I’d say the majority falls under the latter.

Lastly, I told you this will be a multipart series. What am I planning for the next part in the series? Well, I’m not sure when this can/will happen, so I doubt this will be the very next post, but I’ve been thinking about setting up my own OpenFlow network, and going through the process myself. As soon as I do that, rest assured that this blog will house my documented journey through the process. I do think this technology has promise, but right now, only for a select group of users, such as those that like to poke and prod, and are passionate about networking. Fortunately, I fall under that description.

If you have any other questions about OpenFlow or wish to submit some ideas for the next article in this series or any other topic on the blog, feel free to post in the comments!