[Virtual Routing] Part 1 - CSR 1000v First Glance

April 16, 2013 in Systems7 minutes

As some of you have heard, the Cisco Cloud Services Router (CSR) 1000v has recently been released for download, and I quite literally pounced on it when I first heard the word. For those that haven’t heard, the CSR 1000v is essentially Cisco’s answer to the problem that has existed in datacenters for a while - that the current multi-tenancy mechanisms, especially overlays like VXLAN and yes, even NVGRE, are just not cutting it for everyone. Some cloud providers need something a little higher on the OSI model, in that they’d like to provide multi-tenancy right through to the virtual layer like everyone else, but with L3 tools like VPN.

I’ll say it now - Vyatta has been doing this for some time. Not trying to start a debate about which product is better, because frankly the CSR 1000v just hasn’t been out for long enough to conclude that. However, this seems to be Cisco’s effort to answer the solution to this problem. The timing is also interesting, considering that the CSR 1000v was announced but still technically under heavily development right around the time that Vyatta was being acquired by Brocade. Hmm…

If you’re used to the architecture behind the Nexus 1000v, leave your preconceived ideas at the door - this is not nearly as elaborate. Long story short, the CSR 1000v is just a VM. It’s not a structured web of relationships between VSM and VEM like the Nexus 1000v is, but rather a single VM that’s loaded up as a single appliance, with multiple virtual NICs, representing routed interfaces.

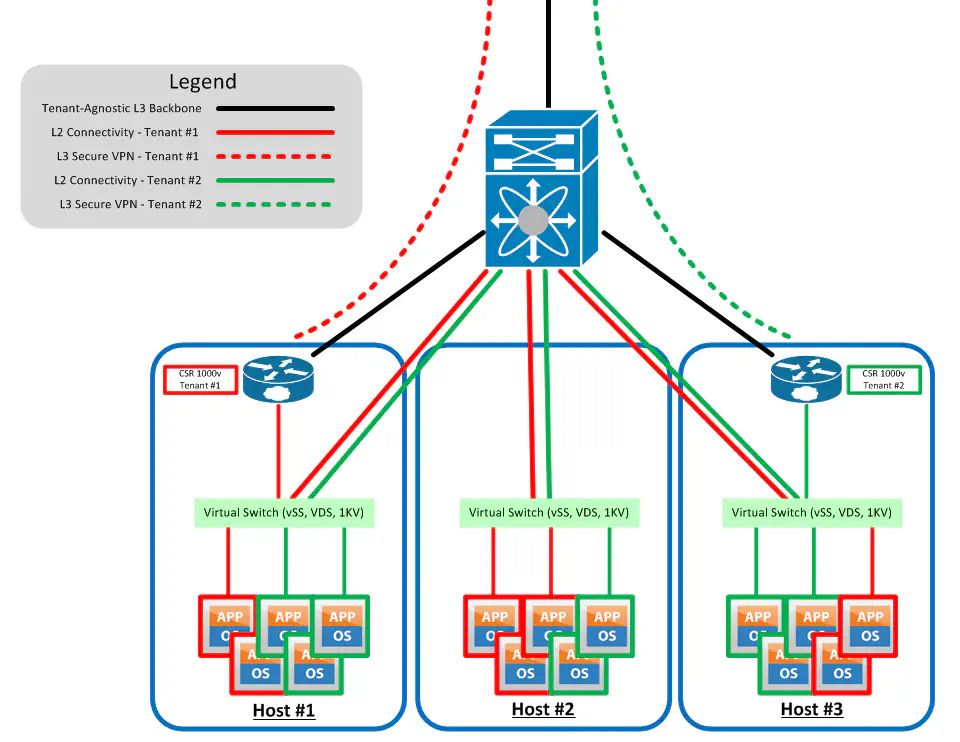

By extending the L3 boundary into the virtual environment, you’re providing a security boundary at less cost to latency. Don’t have to go through 3 or more switching hops to get to a router, when you’re likely to just get sent back into the POD anyways. The key is maintaining secure multi-tenancy throughout the transport between the customer site and their slice of the datacenter. This way, we can extend VPNs (MPLS or otherwise) directly into the virtual environment, all the way from the customer’s location. The CSR supports EasyVPN, FlexVPN, and DMVPN to name a few, and is also able to use GRE tunnels or MPLS L3 VPN services to provide transport for clients. The CSR 1000v uses IOS-XE, the same OS as the ASR 1000.

Key Points from Cisco

After my research, I feel like Cisco’s most proud of the following features, as they are on nearly every piece of marketing material on the product:

The Route Processor, Forwarding Processor, and I/O Complex are multi-threaded applications, meaning that the CSR1000v can take full advantage the latest innovations in processor technology. (This is a fancy way of saying “We at Cisco think there’s some potential in x86 too.” Totally NOT Vyatta though, you guys.)

They say the platform has been built to be hypervisor-neutral. I was only able to find cases where it was implemented in vSphere and XenServer, but it makes sense that it wouldn’t have any hypervisor dependencies, since it’s not as intricate a solution like the Nexus 1000v.

Lots of VPN features, and supports most widely used routing protocols.

Programmability - REST and XML API, plus Openstack integration? Also, I assume this will support onePK, since we’ve been told that all existing platforms will support it.

These were my paraphrased versions of the points I heard from this video - let’s down the kool-aid and take a look:

Architectural Implications

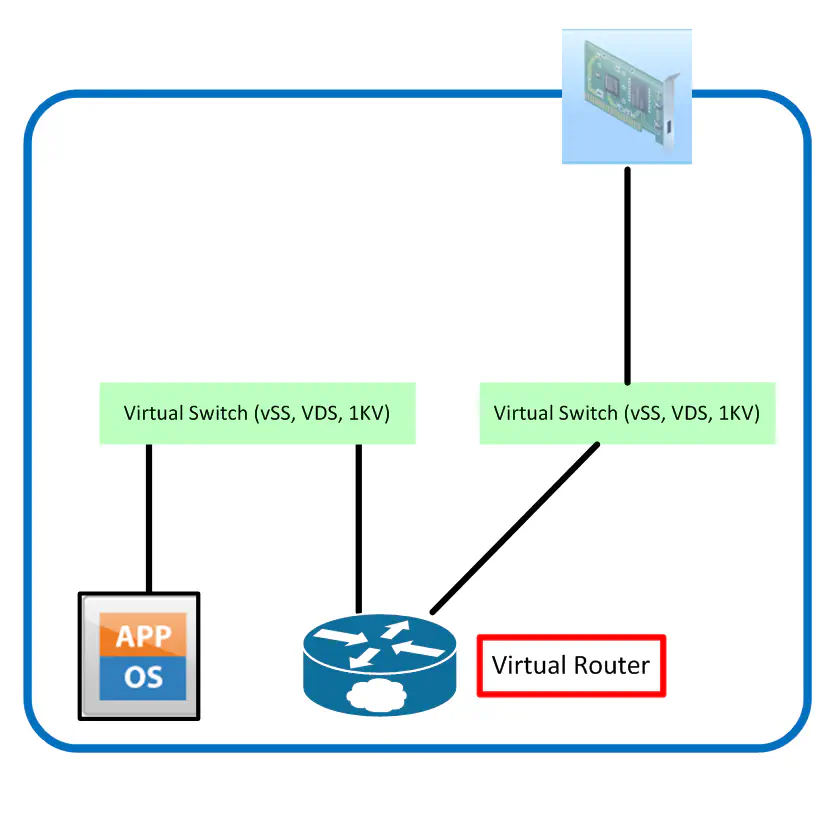

It’s important to take a step back and think about what this video was really all about - features. Yes, there are a lot of things this device can do, especially considering that it is essentially full-blown Cisco software as a virtual machine, which is unprecedented in this form. However, given that the architecture required for this solution is pretty much the same as pre-existing solutions like Vyatta, it really will come down to who does it better, with more relevant features, at a better price point for the performance you’re getting. Given that the goal is to extend those fancy L3 features as close to the VM as possible, you might want to provide direct access to a CSR on a per-host basis, so the CSR can be used for the traffic flow before any traffic leaves the host.

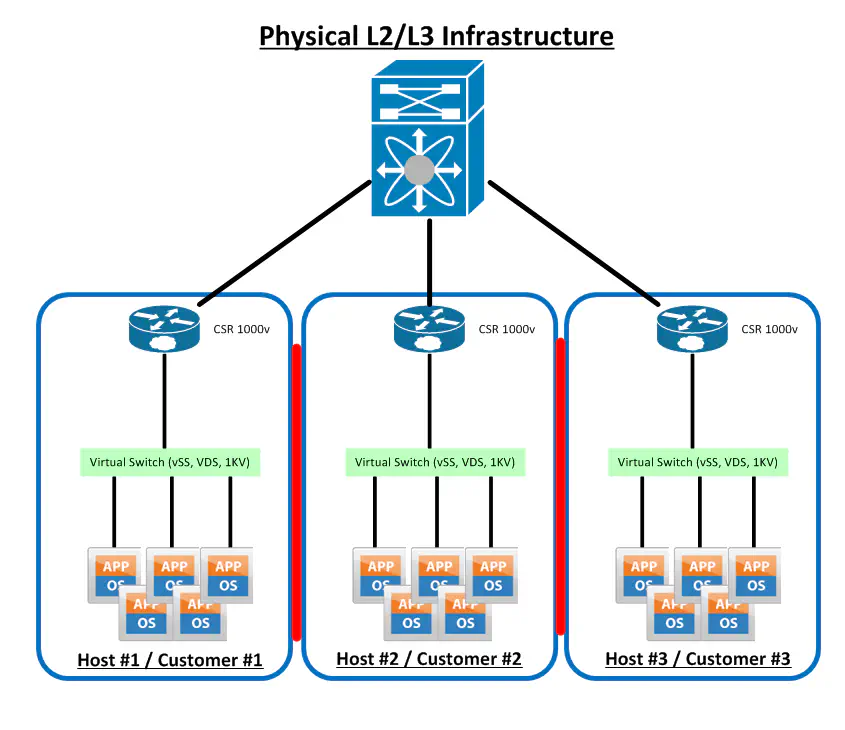

Obviously this scenario is not ideal - while it does provide us with a routing function for each host, it doesn’t really gain us that much, especially since VM migration in this scenario isn’t really feasible. (Okay it’s possible but it defeats the purpose of keeping traffic local to the host prior to getting CSR treatment, so the point is moot.) If you do decide for some reason to keep VMs local to the host their router is on, you lose the benefits of virtualization in the first place - resources that a certain tenant isn’t using will continue to go unused. A more proper design might look like this:

This looks a lot better. This follows Cisco’s recommendations of using one CSR per tenant, rather than one per host. Since L2 connectivity is still provided with as few hops as possible (you can use a few tricks to keep traffic as close to the hosts as possible - using only a single uplink in UCS is one example) we get the luxury of not really caring where in the infrastructure our VM is, as long as it has L2 access to the virtual switch that our CSR’s VM-facing interface “plugs into”. Yes, this does mean that for the majority of traffic flows, an extra stop to some other host is necessary in order to get CSR treatment, but engineered correctly, this might not matter.

Blade computing has a leg up here, since I personally would be much more comfortable with this extra hop if I could keep the traffic at the very least in the same rack, or even better in the same chassis. Regardless, proper L2 design will result in this extra hop not costing you too much. Interestingly enough, the CSR data sheet does list HSRP as a supported option, so it could get even more interesting when you consider spinning up two CSRs and use anti-affinity rules to keep them apart, then configure them in an HSRP standby group so that if one host fails, the standby router will take over. Whether or not this is a better form of failover than HA or FT has yet to be discussed, but could make for an interesting blog post. (Yeah, it’s already in drafts - don’t judge me.)

VRRP and GLBP is also supported - I have a CSR spun up in the lab and just checked on this.

One confusing message I was getting from Cisco - they mention that I/O passthrough could also be leveraged here, giving the CSR direct access to the network hardware without having to go through a vSwitch. This will further restrict VM mobility, as this will obviously prevent vMotions or similar. Same rule as creating Raw Device Mappings in vSphere - if you create stateful mechanisms, you lose the ability to be stateless with the virtual machine as a whole.

After all, what the point in having a cloud if you’re binding a virtual machine to a specific point in the infrastructure, virtual or not? In summary, all of these architectural implications apply exactly the same way to a Vyatta or similar implementation, since both fit into a virtual environment in exactly the same way. Not a lot of complexity when you’re talking about a single VM that must be part of the traffic flow - spin up a few virtual NICs and route between them.

Conclusion

Future posts will be exploring specific implementation of the flagship features in the CSR 1000v. For now, I see some nice integrations with Cisco-proprietary technologies like EIGRP/DMVPN, but other than that, this really seems to simply be Cisco’s alternative to Vyatta - at least architecturally speaking. Thus, it’s all going to come down to feature sets - which solution provides better/more features that are needed for their target audiences? Are the target audiences even the same?

These are questions I’d like to be answering in the next few posts of this series. Please let me know if there are specific aspects of either that you feel are most relevant. By the way - setting this up in a lab is quite easy, and for the time being seems to be something Cisco doesn’t mind too much - the “trial” period is performance-based. By default, the bandwidth through the system is limited to 2.5Mbps. With the installation of a trial license, this can get bumped up to the (current) maximum of 50Mbps. When the trial expires, it goes back down to 2.5Mbps.

Resources

- Cisco Data Sheet on the CSR 1000v: http://www.cisco.com/en/US/prod/collateral/routers/ps12558/ps12559/data_sheet_c78-705395.html

- CSR 1000v Installation Guide: http://www.cisco.com/en/US/docs/routers/csr1000/software/configuration/swinstallcsr.html