Cisco VM-FEX and the Nexus 1000v

June 10, 2013 in Systems9 minutes

Many of those that have supported a vSphere-based virtualization infrastructure for any length of time have probably heard of the Cisco Nexus 1000v. I’ve written a few posts that mention it, and I’ve been deploying the product quite successfully for the past few years. Even cooler, the Nexus 1000v is now available for Hyper-V as well.

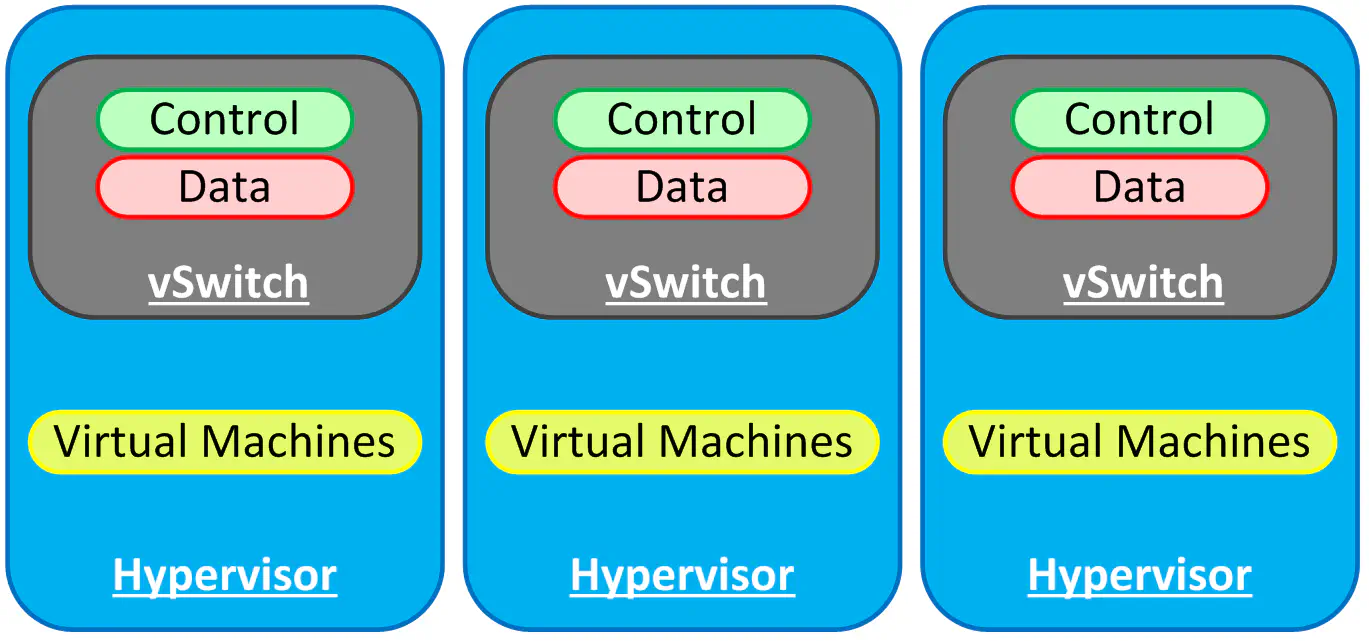

For those that are not familiar with the idea of distributed switches in general, I’ll overview the concept briefly. Let’s assume you’ve got a virtual deployment that has quite a few hosts. Each host has one or more virtual switches, and each host maintains the control and forwarding functions locally inside the software switch of the hypervisor.

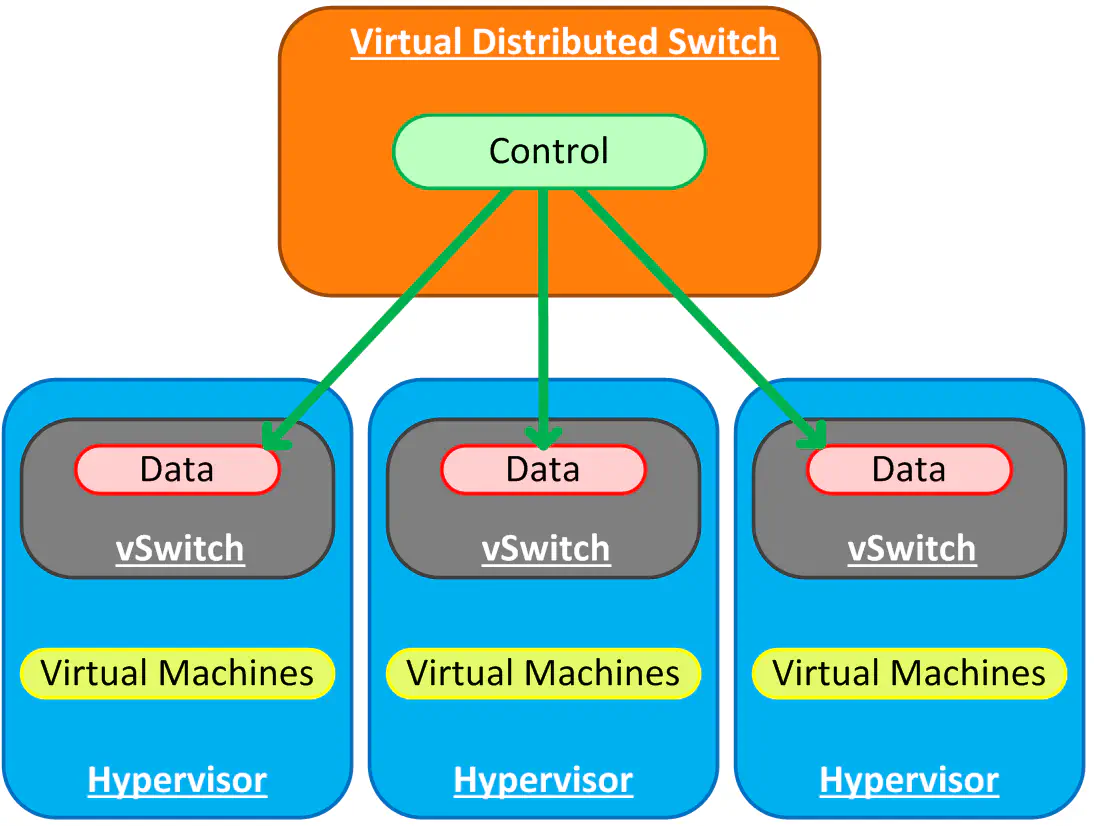

Eventually you tire of administering the individual hosts’ vSwitch configuration to make changes, so you decide to figure out out to do it centrally. Those that lean more towards a virtualization skillset tend to opt for the VMware Distributed Switch. Strictly speaking, and especially for the purposes of this post, the VDS is merely one type of distributed switch. The general idea is that the control and configuration functions of a vSwitch are abstracted, leaving only the software needed to actually move packets around (data plane). This allows for a centralized point of management and control.

This is a logical diagram of course - the vast majority of deployments (for either VDS or Nexus 1000v) results in the control plane actually residing on a virtual machine in the environment being controlled. Does this sound dangerous? It is -unless you know what you’re doing and remember not to trip over your own virtual cables.

Nexus 1000v

I mentioned that the VDS is really one implementation; in this diagram, the function of “control” is fulfilled by vCenter. Let’s refer back to our scenario, and say that you’re either a Cisco-savvy virtualization administrator, or that someone else is, and you’d rather they manage the network switching functions in the hypervisor. This is a good use case for the Nexus 1000v, where the data plane is fulfilled by a Cisco Virtual Ethernet Module (VEM) and the control plane is fulfilled by the Virtual Supervisor Module (VSM). However, the architecture is the same - abstracted control plane, distributed forwarding plane.

Want to know what it’s like when this whole architecture is driven by Open Source Software? Check out Open vSwitch - wicked cool stuff.

The Nexus 1000v VSM is run either as a virtual machine inside the environment, or inside a separate piece of gear called the Nexus 1100 appliance. (It’s basically a server with a locked-down hypervisor on it. By the way - it is not a friend of mine.) The benefits of the VDS in general are realized here, with some added benefits like the familiar NX-OS CLI for those that want it, plus a myriad of features that the VMware VDS still has yet to implement - most notably in my opinion: CoS tagging for virtual port groups.

The Nexus 1000v works by communicating directly with the virtual line cards inside each host using a Control VLAN, as well as direct communication with vCenter, for things like syncing configuration of port groups, etc.

VM-FEX

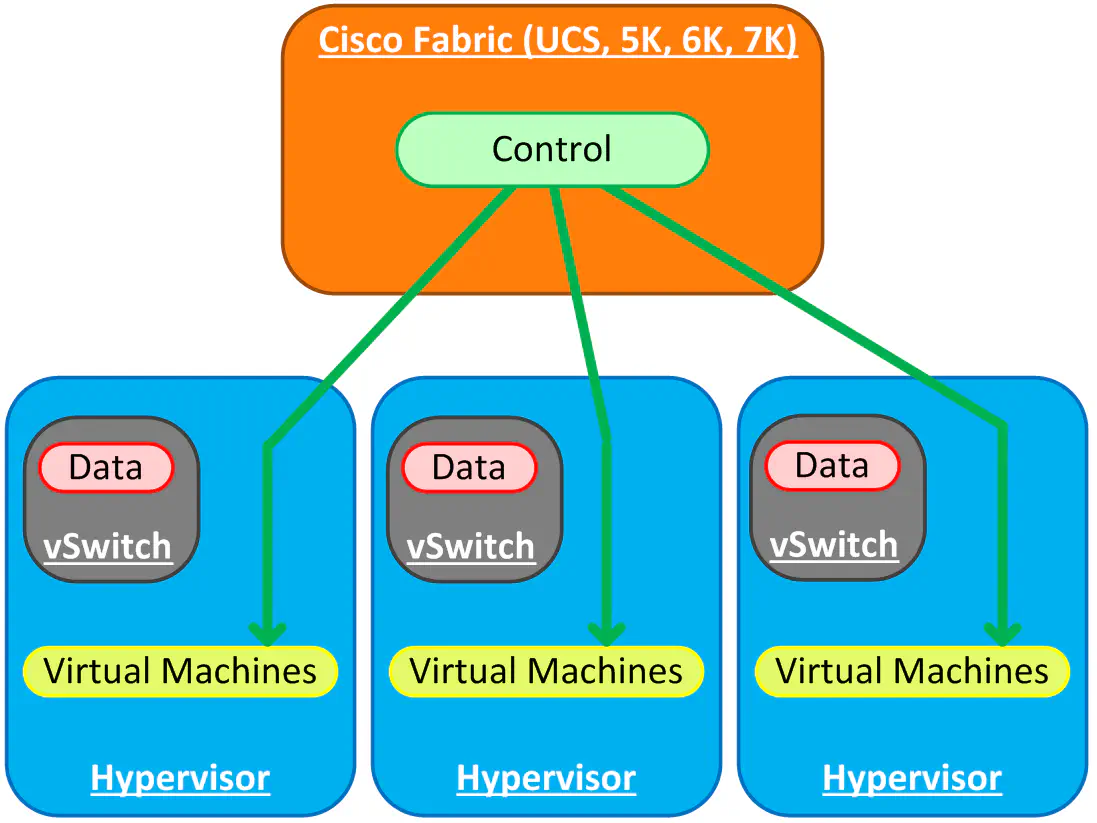

VM-FEX is actually not too different from the Nexus 1000v in terms of architecture. Both solutions utilize a Cisco-created software module for distributed forwarding functionality (VEM). However, the control plane is found in a different location than with the Nexus 1000v, and the reasons why you would use VM-FEX are quite different, in my opinion.

First off, if you haven’t seen the below video by UCSGuru, take a moment to watch - it will be worth your while, and he does a far better explanation of VM-FEX (and FEX in general) than I could do here.

As you can see, the purpose of VM-FEX is twofold: first off, we want the control plane to reside in some kind of central location, most likely the top of rack or end of row switch. This means fewer points of management while maintaining scalability. The other purpose is to push (or extend - see?) the fabric ever closer to our workloads/virtual machines so that this simplicity is realized within the hypervisor.

The Nexus 7000, 6000, and 5000 series switches, and the UCS Fabric Interconnects (remember that “VM” tab that no one ever touches?) are all able to serve as the control interface. This means that we can manage the remote “linecards” that represent each host through a central point, same as the Nexus 1000v.

That’s not the only difference between VM-FEX and the Nexus 1000v - in my opinion, if it just came down to centralized management, the Nexus 1000v is a much better way to go, but we’ll get to that. VM-FEX goes a step further, allowing virtual machines to plug directly into the fabric being presented (Either a Nexus switch or Fabric Interconnect). Just like all FEX technology from Cisco, this is loosely based on 802.1br (Cisco’s flavor is VN-TAG). As you saw in the video, a big reasons to run VM-FEX is indeed the centralized management component - it, like the 1000v, creates a VDS in vSphere, and allows you to administer the available network port groups from a centralized point. However, with VM-FEX being a hardware-based solution, you get to plug each virtual machine directly into the fabric (The limit with the M81KR is 116 virtual adapters per host).

Cisco says that the 1000v is designed for configuration simplicity - offering a comfortable NX-OS CLI in the virtual space, designed for non-critical virtual machines only. Their recommendation for all “critical”, gotta-be-up-or-bust systems, you deploy VM-FEX.

By the way - VM-FEX can now also be deployed with Windows Server 2012 and Hyper-V. Since the Nexus 1000v and VM-FEX both use the Cisco VEM software module to allow the control plane to interact directly with the hypervisor, both products can now be used with Hyper-V .

Pros and Cons

Hardware Requirements - A Cisco VIC (i.e. 1240, 1280 or m81KR “Palo”) is required to perform VM-FEX in hardware. There are ways to perform VM-FEX using software, when cards from QLogic or Emulex are present, but this defeats the purpose of VM-FEX in the first place, so the point is moot. Bottom line, if you really want to take advantage of this, you need a Cisco VIC, which means you need to be running Cisco UCS. The 1000v is a software solution, so the compatibility requirements are with the hypervisor and management software (like vCenter), not with the underlying hardware.

Limitations and Maximums - If you choose to use VM-FEX in VMDirectPath mode, bypassing the hypervisor entirely, keep in mind that you’re still limited to the number of devices that ESXi can support per host for this function. The vSphere 5.1 documentation points out that you’re limited to running only 8 VMDirectPath PCIe devices per host, and 16 per virtual machine. The 1000v has limitations but they are not very scary. Something like up to 64 hosts/VEMs, 1024 vEthernet interfaces per port profile, 32,000 MAC addresses per VEM, you get the point. And it’s not a hardware solution, so scaling it may not be better, but it is simpler.

vMotion Support - Prior to vSphere 5, deploying VM-FEX in VMDirectPath mode meant preventing vMotion of all involved virtual machines, as there was no way to communicate this move to the fabric. Check out this good overview by Ivan, the trick used here is pretty cool, and it solved a pretty big problem with VM-FEX. Virtual machines connected to the Nexus 1000v have and will be able to vMotion, as the 1000v is merely a replacement for the already software-based virtual switch per host.

Conclusion

I won’t lie - prior to conducting my research, I wasn’t optimistic about VM-FEX - I barely ever hear about it being deployed, and there’s still the glaring truth that should be acknowledged, which is that you have to have a pretty big Cisco investment to even think about it (Ivan calls VM-FEX “the ultimate lock-in”). However - for shops that don’t mind buying Cisco for a while, VM-FEX is not all that bad.

If I were to argue against the deployment of VM-FEX at this point, it would be for purely architectural and operational reasons, and those always depend on many factors. For instance, the Cisco 1000v is a software hypervisor switch, and east-west traffic has the potential to stay local to the host. Any FEX technology means that traffic MUST travel back north to the fabric device before being switched, so even two virtual machines on the same host must hairpin traffic up there in order to talk. The part that “depends” is the fact that this N-S traffic flow might not matter that much. It’s likely you won’t be running into bandwidth constraints, and the latency caused by such a hop is pretty negligible. Again - it depends on your applications.

The other big thing to consider here is administration. If you’re deploying VM-FEX in UCSM, that’s another pane of glass to touch - most shops will get into UCSM a fraction of the amount of time they spend in the switch CLIs or vSphere client. VM-FEX from a straight Nexus switch isn’t that bad, but it still means that someone familiar with a Nexus CLI (usually not a virtualization admin) will have to administer the virtual realm’s networking. Sometimes it’s a sharp learning curve, sometimes it’s not. Again, it depends.

Frankly, I don’t believe VM-FEX should be thought of as merely an alternative to the 1000v. While you can’t really run the two simultaneously on a host, I believe that if it was a question of management simplicity, the N1KV is more than an acceptable choice. Use VM-FEX if you not only want this centralized management but also the other features VM-FEX offers.

For instance, we haven’t each started talking about the performance gains VM-FEX claims to provide. (Read this slideshow - in 2010 Cisco claimed 12-15% CPU performance improvement for standard mode and 30% improvement to I/O performance when using VMDirectPath) The arguments in this space have been going on for some time - some say that the performance is worse with VM-FEX because it means more north-south traffic. Others claim it’s faster because it’s done in hardware as opposed to software (VDS, 1000v), making the extra hop north to the fabric switch insignificant. My findings on this are best saved for another day.