Why We Want to Kill Spanning Tree

June 18, 2013 in Systems6 minutes

To say that Ethernet as a L2 protocol is well-known is an understatement - it’s in every PC network card, and every network closet. Back during the inception of Ethernet, the world needed an open, efficient, standardized method of communicating between nodes on a LAN. Widely regarded as the “mother of the Internet” for many reasons - not the least of which is the invention of the Spanning Tree Protocol - Radia Perlman equated the wide proliferation of Ethernet to the same events that have made English such as popular language on Earth. It’s not necessarily the fact that English is by any means the “best” language, it’s the circumstances during the formative years that determine the future.

I want to take a second to call out a very special resource that I encourage you to take the time and watch. It’s almost an hour long, but it’s worth it. Hearing about the history behind all of the protocols we now use and probably largely take for granted, in addition to the math behind it all, is a great way of getting perspective.

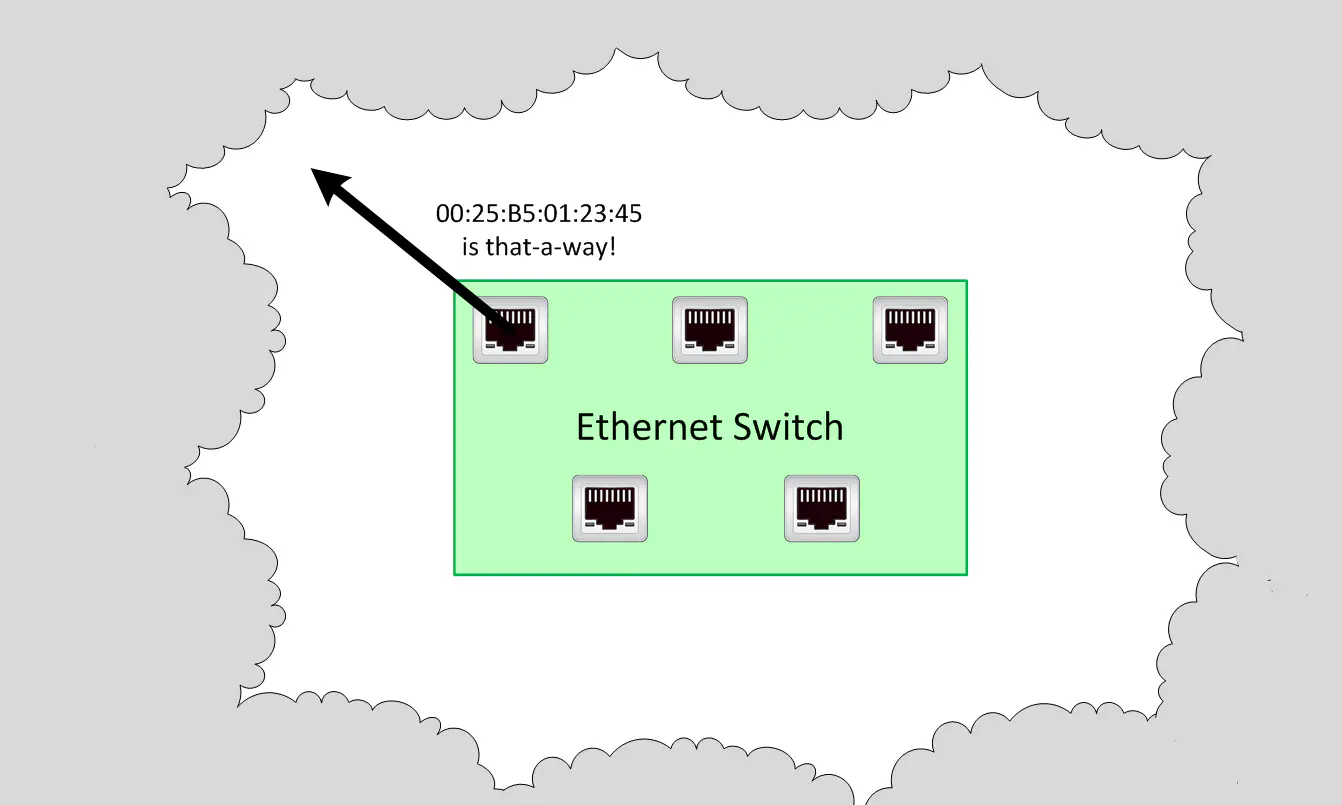

An Ethernet-based LAN is commonly referred to as a “broadcast” network. Any CCNA can tell you that a broadcast domain is the area in which a broadcast sent by a single node reaches all other nodes. This is a data-link layer concept, but easily most widely attributed to Ethernet. First off, if a unicast destination address of an Ethernet frame is not known to a switch, it will be flooded out all other ports by default. This is Ethernet’s way of giving the Ethernet frame the best chance at reaching it’s destination. Also, any frames addressed to FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF are forwarded out all ports.

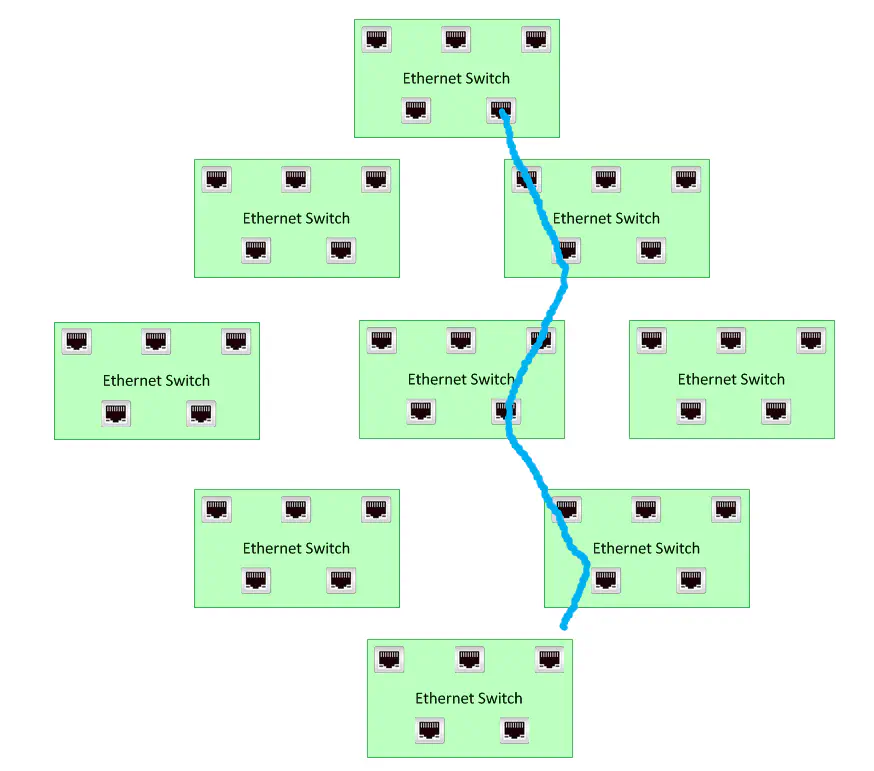

Ethernet has one way of preventing loops, and that’s split horizon - meaning that broadcast frames entering a switchport are not re-sent out the same port that it came in on. However, if a loop is formed using more than 2 switches, (as is common) then this rule would not apply. As Radia pointed out, Ethernet was not originally meant to be forwarded - it was originally meant to provide link layer connectivity between two points. The Ethernet header has no hop count like a Layer 3 protocol does, so loops can get out of control with only slightly complicated topologies. So, Spanning Tree was born to serve as the other loop-prevention mechanism. Find the less preferred path(s) through the switched LAN and effectively disable them, which is the most barbaric way of creating a loop free topology.

The general consensus is - spanning tree sucks. Obviously Radia invented it for a reason - STP is actually very valuable, seeing as without it, our networks would loop out of control. However, therein lies “the beef” - we hate STP because it is necessary. Ethernet is inherently a broadcast-oriented protocol, and the very native functionality of switching is what’s responsible for causing loops. Using STP means that we have to kill valuable bandwidth that we as customers have purchased. Why can’t we use that port that’s been turned off?

Meanwhile, Layer 3 and the protocols used to build Layer 3 topologies (i.e. routing protocols) function ENTIRELY differently! The forwarding decision is different, loop prevention is handled much differently (more than just the addition of a hop count).

Thinking about all of this, I had an epiphany:

Classical Ethernet is to a distance vector routing protocol as TRILL is to a link-state routing protocol.

As an Ethernet switch, you learn a MAC address on a port by looking at the source address on received frames. You know that traffic destined for that address needs to go out that port, but that’s it. You don’t have a holistic view of the network. An Ethernet switch’s perspective is completely locally significant.

This egress link may be the best way out, it may not be. I’ll tell you one thing - if STP decides that link needs to be blocked, it won’t matter anyways.

At the end of the day, this isn’t that great. Ethernet isn’t used for L3 connectivity for just this reason - suboptimal routing choices are made because of this limited perspective, and we’re not using IP to make these forwarding decisions because IP works on another level entirely - namely, to move packets from one Ethernet to another, or to other mediums. Distance Vector routing protocols in L3 function very similarly - they use metric math to figure out a loop-free topology, because they only know the small amount of information about each prefix that a neighboring router will tell it. There is no holistic viewpoint. This is the reason why distance vector is commonly referred to as “routing by rumor”.

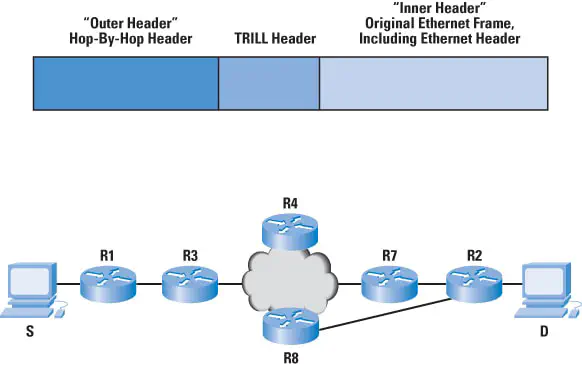

So…we need to find a way to move frames through an Ethernet by using similar forwarding mechanisms to IP, but still look like an Ethernet. Enter TRILL, stage right.

TRILL takes the best parts of link-state routing protocols (neighbor relationships, full knowledge of topology for better forwarding decisions) and applies it to Layer 2. Now, we have bridges that have holistic views of the network, and are able to intelligently deliver frames along every path. We no longer need to kill a link to deliver a loop-free topology.

Fun Fact: IS-IS was chosen over OSPF for a few reasons, but a notable one is the fact that OSPF is pretty much purpose built for IP/IPv6. IS-IS works directly on top of Layer 2 so there’s no need to mess with IP addresses in the configuration of TRILL.

Since TRILL operates by encapsulating the original Ethernet frame and “routing” it at Layer 2 intelligently, we don’t need to rewrite our host networking stacks. Even unknown unicast addresses don’t cause problems, because the TRILL LSDB has enough information to get the frame to where it needs to go. (we just care about getting to the last or egress rbridge). On top of a TRILL header, we have a completely new Ethernet frame on top of it all, where the addressing is done on a next-hop basis (sound a little like IP routing now?).

Conclusion

I didn’t go into detail on FabricPath specifically in this post, but I will mention this article by Cisco on TRILL which is actually co-written by Radia Perlman. It’s a pretty good explanation of the reasons behind TRILL and how it works on the inside.

At the end of the day, TRILL is a step towards the original intent that we should have had for our LANs but because of the history were never able to achieve. Think of all the things we’ve learned about IPv6 now that it’s approaching higher adoption rates. It’s impossible to anticipate every little problem that a protocol may produce, but bandaids like STP and TRILL are necessary to continue to evolve the network, and overcome the scalability challenges that are being presented every single day.