[Overlay Networking] Part 3 - The Underlay

September 5, 2013 in Systems11 minutes

We finally arrive at the physical topology that all of the stuff I discussed in the previous posts is built upon. “Underlay” is a term that is starting to catch on - this describes the infrastructure that all of the overlay networks ride on top of, and I’ll be using it to describe this physical infrastructure in this post. Keep in mind the term is used no matter how our physical infrastructure is laid out - there’s quite a few different ways to build this thing.

One of the benefits to overlay networking is that the underlay has the** opportunity** to be made much simpler - but it doesn’t happen automatically. The best chance for an organization’s success in adopting overlay networking technology is if the server and networking teams work together to make both their lives simpler. When this happens, the biggest benefits can be realized.

Underlay Thoughts

While the underlay is being made MUCH more simple in this mode, keep in mind that it’s still important to have a solid foundation, otherwise your overlays aren’t going to run very well, will they?

In an overlay world, the biggest role of the underlay network is to provide an IP network for the hypervisors to talk to each other. The overlay traffic is simply an application that rides on top. There are plenty who will scoff at the “everything-is-an-application-over-IP” notion, but it’s a compelling one.

A data center network without VLANs (or at the very least a severe reduction in their use) does tend to win the “stability” argument. Since we’ve used them for so long, we forget that VLANs are a very volatile technology; not only for the simple reason that STP is a pain, but Ethernet is a flooding technology when you get down to it. We can’t get around that, we can only move towards a point-to-point mentality.

By the way, Radia Perlman talks extensively about the history behind Ethernet in her famous talk at Google. Ever wonder why Ethernet doesn’t have a TTL field like IP does? It’s not that they didn’t think of it - the creators literally didn’t think anyone was going to be forwarding based on layer 2.

So, the original intent for Ethernet was used in point-to-point implementations, not so much switched LANs. This is essentially what we’d be reverting to in the data center, with each link it’s own Ethernet domain, and all of our network devices turn into port-dense routers.

I took to twitter to discuss this, and had the following conversation:

Spoke with a switch vendor today who are not planning to implement L2 ECMP (TRILL or SPB) because overlay networking is the market.

— EtherealMind (@etherealmind) August 21, 2013@Mierdin No STP in a L3 ECMP core. Overlay networking doesn’t use VLANs.

— EtherealMind (@etherealmind) August 21, 2013The result - turn each link into a broadcast domain, and get rid of VLANs. We can do this because our logical network separation is now being provided by our overlays. This is a very different way of thinking for many, and there will always be a large chunk of the industry that won’t go for it.

There’s also talk that overlays (or more specifically, the fact that we’re getting rid of VLANs) might just be the kryptonite for L2 multipathing like TRILL. This is because technologies like TRILL are methods of getting around Ethernet, or Spanning Tree, or whatever you want to call it. The alternative, which is simply a purely L3 data center, gets rid of Spanning Tree entirely - STP doesn’t run on a Layer 3, or routed, port.

I share the belief that all of this talk of overlays killing off technologies like TRILL is certainly not a reality today, but I also see there’s a ton of momentum behind the overlay movement and that the move to an all-routed DC is inevitable, given the benefits. It’s just not going to happen tomorrow.

I'm almost ready to call it. The solution to multi-pathing in Ethernet will likely be overlay. Too much momentum. TRILL had its chance.

— tbourke (@tbourke) August 28, 2013These two solutions may work, and they may be two ends of the spectrum, and both are definitely disruptive to “business-as-usual” for DC networks, but the TRILL argument has had to deal with slow adoption rates, compatibility problems, licensing schemes that don’t make sense, and so forth. The overlay concept merely requires an IP network. That’s “Internet Protocol”, guys. You tell me which one is more widely accepted and mature.

We will, however work through a few key design challenges that are important to address in your underlay in the next section.

Underlay Design

So I’d like to talk about some designs I’ve been hashing about in my mind for the past few days. These designs aren’t mutually exclusive - there’s going to be some areas where bleed-over is necessary, depending on your hardware and software involved, but they’re different enough fundamentally that it warrants some specific points.

I’m going to assume that a key design element is the avoidance of spanning-tree, one way or another. In data center network design, that usually a big deal. So all these designs will keep that in mind.

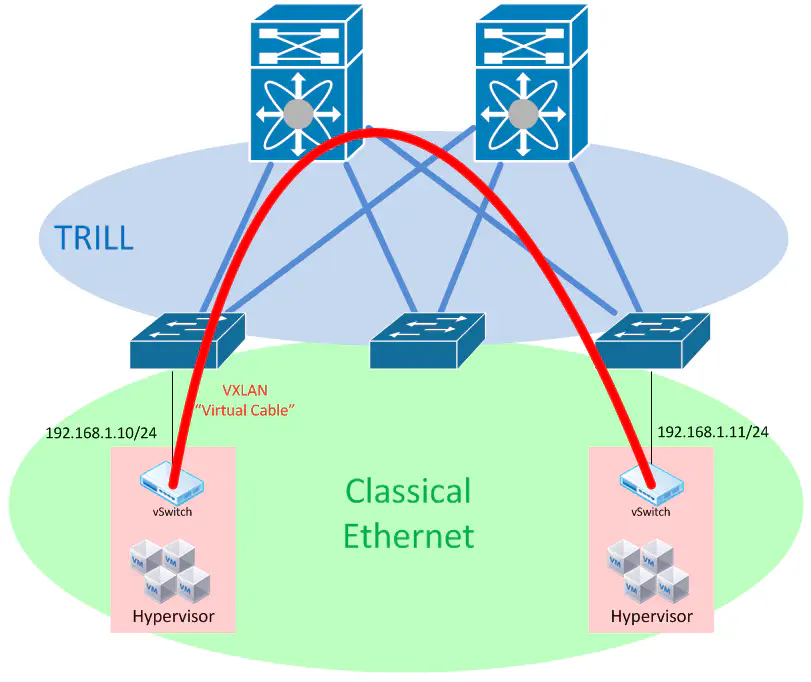

Design #1 - TRILL-based Data Center Fabric

Let’s say you have a pair of switches at your core, and the latest purchase allowed you to bring TRILL out to your ToR switches, to which your hypervisors connect.

TRILL is a technology that allows us to eliminate spanning tree by applying shortest-path logic to forwarding decisions at Layer 2. This means that can can still enjoy the benefits of a topology that is forwarding on all links but still provide layer 2 connectivity between hypervisors.

Ultimately this design comes down to some pretty simple things - if you’re comfortable with TRILL, and your hardware and licensing scheme (sucks, don’t it?) allows you to run it, then sure, this could work. Keep in mind that TRILL - in almost every implementation - has some proprietary additions built onto it that make it non-interoperable with other products, so while this may technically work, it’s probably going to represent a little bit of lock-in.

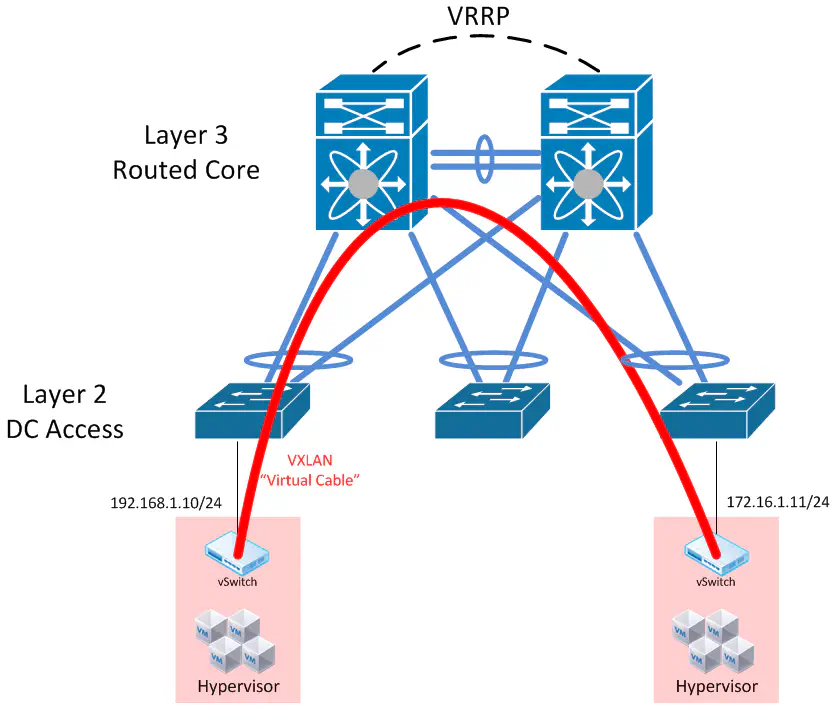

Design #2 - Multi-Chassis Link Aggregation (MLAG) with Routing

So maybe you don’t want to buy into the whole TRILL thing. There are many data centers that haven’t made the jump for the simple reason that they’re happy with the shiny new Multi-Chassis Link Aggregation feature that their current switch implementation is offering. MLAG is a fairly popular umbrella term to describe a feature that allows two devices to - in one way or another - form a single logical switch, so that other devices can be dual-homed to these two switches without knowing it’s happening. Notable examples are Cisco VSS or vPC, Juniper Virtual Chassis, and HP IRF, to name a few.

In this case, a proper design might include the following:

Here, we’ve established a multi-chassis link aggregation between each access layer switch (A layer 2 VLAN-aware switch that can do LACP will do just fine). The core switches are connected through some large bandwidth, redundant links, and together establish a sort of “virtual chassis” which makes all this magic work.

Each vendor’s implementation is different, so the key aspects of this design I’d like to call out is that we still have the ability to route our traffic at the core. Depending on the implementation, a first-hop redundancy protocol like VRRP may be required (For instance, Cisco VSS unifies the control plane for both switches so it does not need VRRP. Just a single SVI to serve as the VLAN gateway)

If a FHRP is used, make sure the vendor’s MLAG implementation supports the necessary tweaks to avoid unnecessary trips across the switch interconnect.

Specifically with regards to the impact on overlay networking - this still allows us to divvy hypervisors up into different subnets, but it does nothing for our elimination of VLANs in the data center. We’re still using MLAG as an STP avoidance mechanism. We can certainly run overlay networks on top of this, but are we really gaining anything in the underlay? This is a lot of fancy networking stuff to protect what amounts to little more than inter-hypervisor communication, from an underlay perspective.

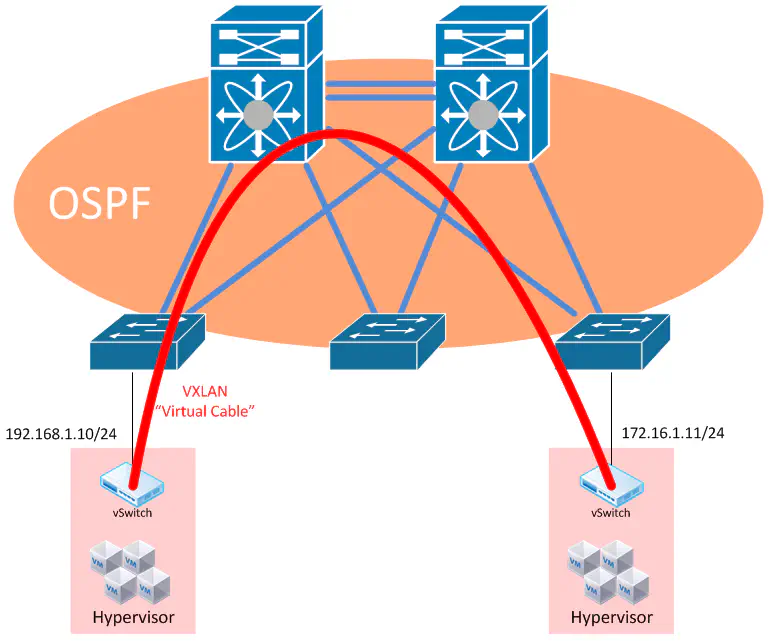

Design #3 - Fully Routed Data Center

And finally we arrive at the third (and in my opinion best) design when it comes to creating a data center underlay. This design is all about one thing - Keep It Simple, Stupid.

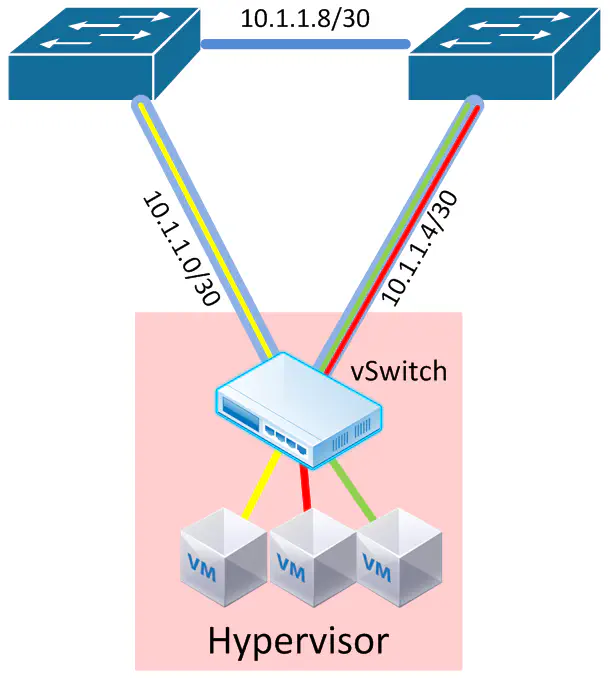

Rather than continue to cope with the complexities of the previous designs, we now have the option of getting rid of VLANs entirely. This results in a data center where all links are not participating in any VLAN, or any spanning-tree domain, but rather are pure routed links.

The benefits here should be clear - we now have a network that’s full-mesh redundant, using protocols that have been used and well-understood for years, such as OSPF for sharing network topology information, and good ol’ IP for transport.

Now - this isn’t something that anyone is going to simply jump into, but some aspects of the other designs may be used during the transition to this state.

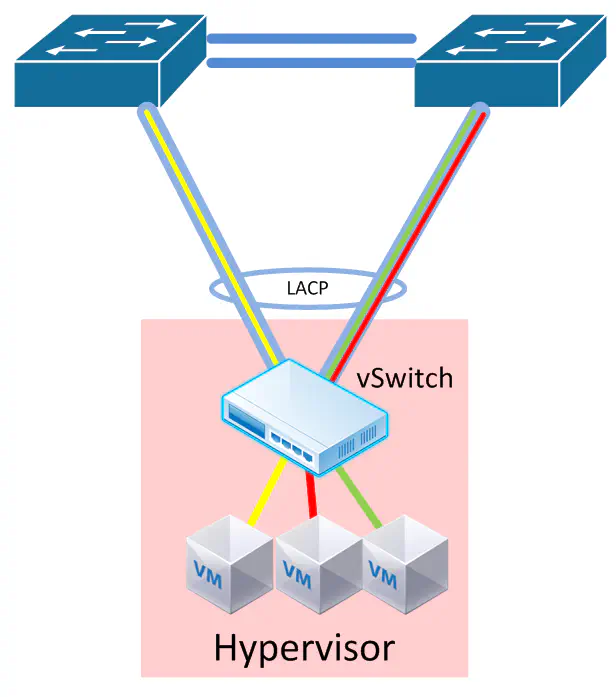

Access Layer Design

Now, you may be asking about the bottom part of all of these diagrams - the single cable to each server. If you’re a big hyper-scale out web shop where you’ve got a million servers that are all fully utilized (probably baremetal workloads too) then you probably won’t care about these next sections, because if you lose a link, or even a single switch, you probably don’t care. However, in the traditional medium to large enterprise, you’re going to need to dual-home a server, probably to two switches.

Right now this the best option. Your best bet is an MLAG technology, or if you don’t care about switch redundancy, then a port-channel to the same switch. In either case, LACP should be used to detect a quick failure.

The overlay tunnels will terminate to a virtual interface (in VMware this is a VMKernel port), and load-balance on the above uplinks. You should use IP src/dest load balancing to achieve the best link utilization, because every frame leaving the hypervisor will come from the same source MAC address. This will by default result in all overlay tunnels running over one link. Not exactly ideal - so make sure you change that policy.

Let’s explore one other design that’s not possible today but would be REALLY awesome if it did work in the future.

Thanks to Ivan Pepelnjak for helping me to wrap my head around some of these key design ideas when it comes to hypervisor integration with the network when we discussed overlay networking and specifically VMware NSX in this episode of The Class-C Block podcast. This section of this post would not be the same without it.

What if - instead of assigning an IP address to a virtual interface within the hypervisor, we could assign an IP address to each physical interface on the host?

This is the true elimination of all Layer 2 constructs within the data center network. No MLAG, no VLANs, nothing. Just routed ports. So why can’t we do this (yet)?

The hypervisor, in this case, would not only have to support the assignment of IP addresses onto physical interfaces, but be able to assign tunnels to each interface depending on link utilization, shortest-path calculations, etc. It would require the software controller to understand how to use each of these links - right now this is not a reality, but definitely a possibility in the near future.

I was brainstorming about alternatives that would lessen the need for the controller to be in charge, and I thought about allowing each hypervisor to participate in the routing protocol. While this might work, it would not be very scalable. Host routes are generally not a good idea, especially if your routing protocol is something compute-intensive like OSPF.

If this is something that comes to fruition in the near future, be sure to use proper IP numbering design and summarization so your routing tables don’t get out of control. Alternatively you may opt to avoid this design altogether to avoid the large number of little /30 networks this could support.

@tbourke TRILL can be complementary so you can avoid a million /30 or /31 subnets.

— Jonathan Topping (@zztoppingdc) August 29, 2013In that case, feel free to use the access layer design I mentioned at the beginning of this section.

End Of Series Rant

When it’s all said and done, the effort behind overlay networking is moving us forward, towards the end goal. Quite frankly I’m not too interested in taking place in conversations that are all about bashing this concept because mostly the arguments are based purely out of ignorance. As are - by the way - many of the arguments that portray VMware as the savior of server admins from those grumpy old network guys who are morons and don’t know what they’re doing. Neither perspective is correct or useful.

At the end of the day, overlay networking solves a large chunk of our problems, VMware was first to market with a solution that included the components we needed. That doesn’t mean that tomorrow won’t see another awesome product. Is it the expected Insieme announcement from Cisco? Maybe, maybe not. In the meantime let’s drop the fanboy stuff and learn about all of this together.

Martin Casado himself says it very well - we’re finally moving out of the slide decks and into implementation. Powerpoint debates can finally end - now let’s go make the networks of tomorrow.