Virtual Networking and the Concept of Abstraction

September 3, 2013 in Systems8 minutes

There’s a lot of talk about “network abstraction” lately in circles where it wasn’t discussed before - all thanks to our friends at Vmware and the announcement of NSX at VMworld. For around the past two years I’ve been doing my best to stay involved in the SDN conversation - while it’s still really new technology, it’s fun to debate about and great to help define the next era of networking. So the idea of abstraction isn’t necessarily new to me, but like SDN itself, warrants a little further definition - after all, everyone has different approaches to solving a problem, and it’s worth taking a look at some specifics. What does it mean to “abstract” the network? Are there different kinds of abstraction? These are some of things that I’d like to cover in this post.

Before we talk about network abstraction we must understand the 3 planes of networking:

Management Plane - technically, this could be tools like SSH, the vSphere GUI, SNMP, XML API, etc. etc. Even you as the administrator take part in the management plane.

Control Plane - this is where decisions are made regarding the forwarding of frames and packets. Usually the control plane receives it’s configuration fromthe management plane; a good example might be configuring EIGRP - the management plane is repsonsible for telling it to run on a router but it’s the control plane that transmits routing updates and installs new routes in the routing table.

Data Plane - this plane is responsible for moving frames and packets through the network. It receives instruction from the control plane, and based on these decisions, moves packets around. No decisions here, just the workhorse of the network.

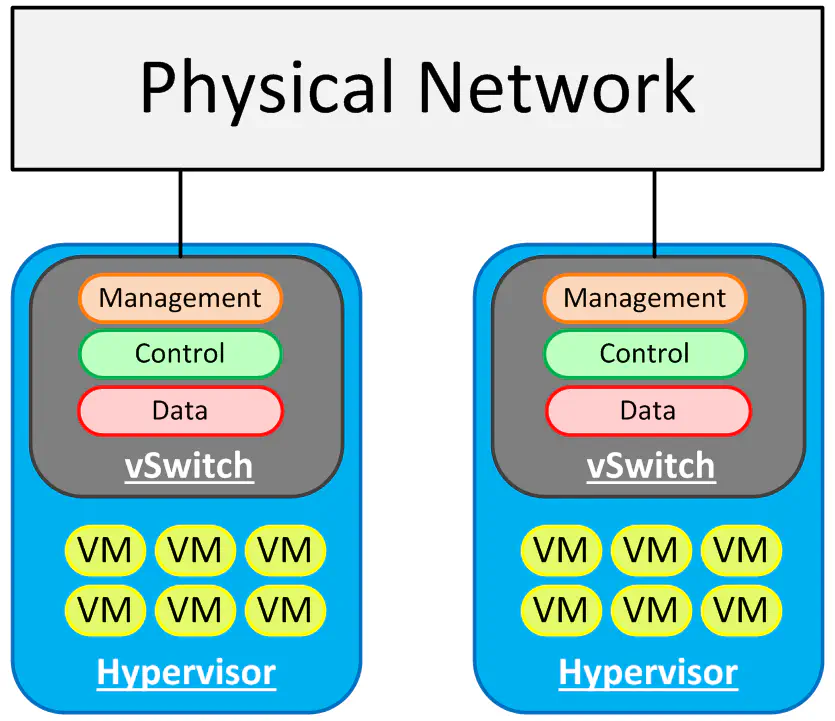

Now - for any hypervisor, we’re going to have at least two things in common. We have virtual machines, and the need to connect them to the network. At the very least, we need to bridge the virtual ethernet environment into the physical environment - the most basic way to do this is what essentially becomes a linux bridge - simply bridging a virtual interface with a physical one. So what do we get when we do this?

Well, for one thing, we get basic connectivity out of, within, and between our hosts. Assume for the time being that this is a standard setup (think small/medium business) where the majority of virtual machines are on the same broadcast domain, and just need to be able to talk to each other. The VMs can talk because they’re using the vSwitch - they can talk to VMs in another host because ultimately they’re all in the same L2 domain. However, all three planes are isolated on each host. Each vSwitch requires direct configuration from the administrator (management plane) and maintains completely separate control information about the network (control plane).

Management Plane Abstraction

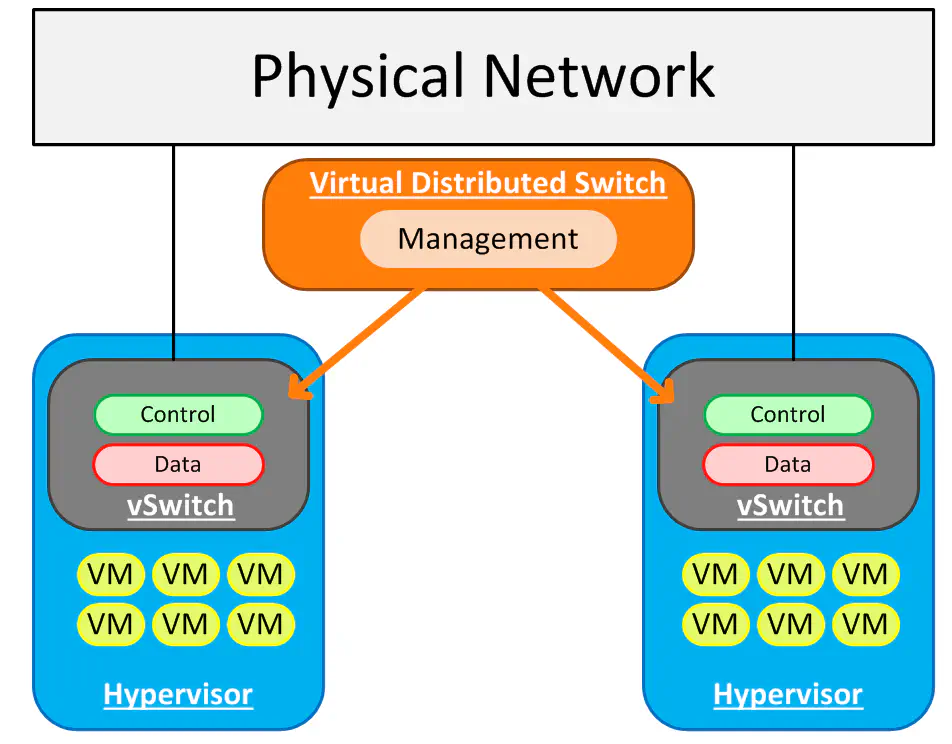

For many virtualization admins, this problem is nothing new. Most VMware folks would use the Virtual Distributed Switch to get around this, by unifying the control If you’re fortunate enough to be in an environment where the networking team and server team aren’t killing each other, you may have heard of the Cisco Nexus 1000v, which is essentially a Cisco module that adds functionality to the VDS - in fact it uses the VDS as it’s method of communicating port-groups and the like with vCenter.

Doing something like this gets you the following:

What we’ve done here is abstracted the management plane so that we can administer our virtual network from a single pane. We’ve merely instructed each vSwitch to open itself up to vCenter, where we’ll be configuring all hosts from the same software.

The benefit to this? Well, it seems like a lot if you’ve spent your life configuring vSwitches individually - and I’ll admit, it’s fairly convenient. However, there’s a bigger use case to be seen here. We still have the same problem where the physical network team has to provision a VLAN on the physical switch for the server team - in this model, the server team just gained the ability to push configs to the virtual environment faster and more easily.

Since it is only the management plane that is being abstracted, we’re not able to do anything with our network beyond the virtual environment - there’s no opportunity for integration with the physical network other than simply to forward traffic onto the link and hope the network can get our traffic where it needs to be.

Control Plane Abstraction

So, if I could switch gears for a second, I’d like to illustrate a basic example of what we in the SDN world have been talking about for some time, and frankly why SDN even became a thing. The networks of today are very much like the first illustration - completely isolated management, control and forwarding planes. There have been attempts at unifying the management plane (see SNMP, Netconf) but they failed in that effort, though maybe became useful for other stuff. Each router and switch is configured by a tech with a console cable or puTTY window, one at a time, with the command line. Geek cred? You betcha. Maintain that kind of a network for a long time? And be agile to serve the changing needs of the business, especially when that business is running a huge virtualization environment? Pain in the ass.

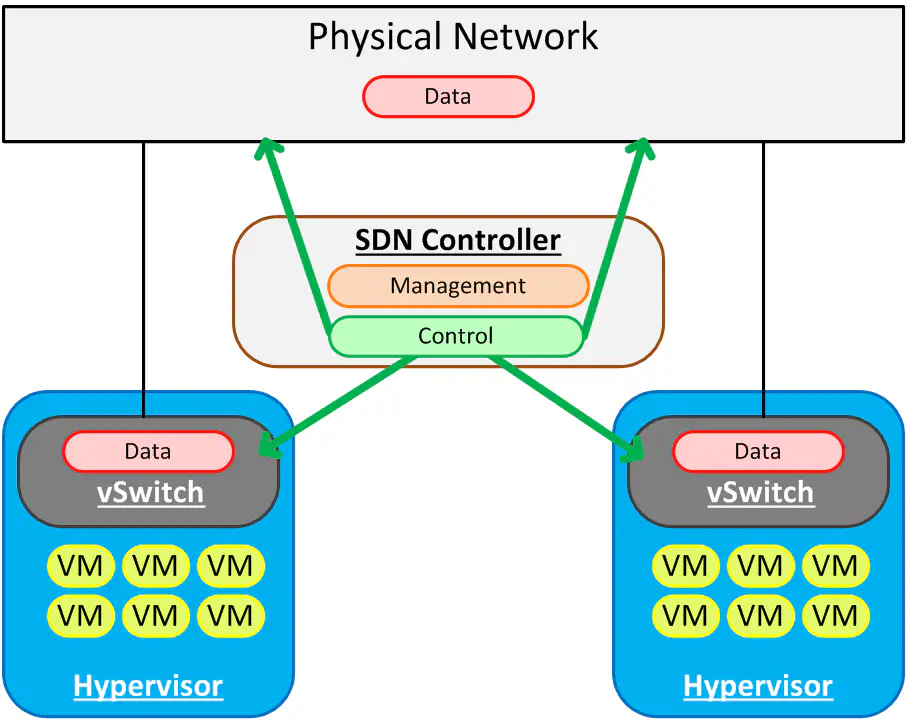

This was where the idea of a controller-based network came to be. If we could figure out a standardized protocol that allows us to centralize the control plane (which would obviously also centralize the management plane), we could push literal flow information down to each device, whether it’s a router, a switch, a firewall, or a virtual switch, etc. In essence, each device would become a dumb forwarding device, receiving instructions from this device on how to forward traffic. By flow** information** I mean the kind of info that you’d see in a switch MAC address table, or the FIB of a router. Even up to Layer 4 information like TCP ports could be part of a “flow table”.

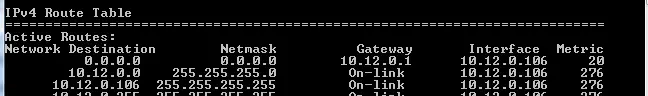

The idea of a flow table, or routing table, or MAC address table is simply to identify traffic, and based off of some kind of criteria, make a forwarding decision. The act of populating such a table is the role of the control plane. The data plane looks at a packet, compares it against this table, and forwards it according to the table’s instructions. Want a really common example? Show the routing table on your local PC:

The management plane (me) instructed windows to place a static route into the routing table (control plane). Now, whenever I try to send a packet to a destination not identified by a route further down in the list, my PC will forward that packet to my gateway, 10.12.0.1, and it will use the local interface with an address of 10.12.0.106 as the method of getting there. (data plane).

This article by Brent Salisbury - definitely someone worth following if you’re interested in SDN or networking in general - highlights some of the ideas of flow-based forwarding.

This “flow table” is merely the result of network forwarding decisions that have already been made by the control plane - essentially how to identify traffic, and where to send it if a certain parameter is met. Since L2-L4 fields are game in this mode, we can get pretty granular with our forwarding decisions, and we don’t have to distribute our control plane to do it. We merely populate the flow table from a centralized controller, and the forwarding devices do just that - forward.

Now - it’s always interesting to note that the virtual switch, (or networking agent, whatever you want to call it) is typically going to be where this kind of abstraction is the lowest hanging fruit - the reason is that it’s always going to be running on a standard x86 architecture that is ASIC-less if you’re talking about standard hypervisors. So, the innovation and the interoperability is greatest in that space.

However, as you may notice, the control plane is also abstracted away from the physical network. We’re at a point now where most folks believe that the physical and virtual should not just be configured from the same pane of glass, but that they should BE the same pane of glass. This is where simple centralized management APIs failed before - we have now dumbed down our forwarding devices to the point where they can simply accept commands from a centralized controller regarding what forwarding decisions were made. Technically, this model completely does away with the need for routing protocols, if you so desire. Of course, at some point you will need to integrate with a network outside your SDN domain so these protocols still have their purpose, but why have them inside, say, the four walls of your data center, if all of your network switches and software routers have had their brains removed and put into a single box that’s running the scripts you wrote last week?

This last model of abstraction is where the SDN movement seems to be pushing the industry, and without going into specific detail, is the closest generalized idea to think about when you hear about new products like VMware NSX, which was announced last week at VMworld 2013. I will be writing a post in the near future concerning that product, and it will refer back here, because the advantages of this architecture are exploited heavily in that product, and I firmly believe that at this point, the momentum of the industry at large is going too far in that direction to ignore.