Introduction to Ansible and SAN Configuration Automation

April 14, 2014 in Systems16 minutes

My previous post on automatically generating a SAN configuration explored what is possible when using a templating language like Jinja2, and a little Python work.

I’d like to take this a step further. There are two areas I did not address in that post.

The typical SAN or UCS administrator likely knows little if any Python. I’d like to produce a tool that is easy enough to consume, and requires no programming knowledge to use.

Pushing the configuration to the SAN switches can also be automated, and the same rules about skillset likely apply here. Those that administer SAN or DC switches tend to be light on programming skills.

After some consideration, and substantial encouragement from other GREAT posts on using Ansible for network infrastructure, I decided to build a few modules of my own so that a few of my coworkers and customers will be able to perform SAN zoning very easily using an Ansible playbook. These modules are designed to be very reusable, and the only requirement is that you know how to pass arguments to these modules the Ansible way. You will be able to use these modules with zero Python experience.

This places the onus of straight-up Python development squarely on my shoulders alone, and allows me to provide consumable, and easily adoptable tools that don’t compromise on flexibility. This puts just as much power in the hands of infrastructure folks, without the added complexity of learning a full-blown programming language.

What is Ansible?

Ansible’s approach to orchestration is one of bare-minimum simplicity, as we believe your automation code should make perfect sense to you years down the road and there should be very little to remember about special syntax or features. –How Ansible Works

Ansible is quite similar in purpose to other popular DevOps tools like Puppet, Chef, or Salt - but like all those tools, very different in architecture and implementation. More on this later. For now, and for the context we’ll be using Ansible in, think of it as an extremely easy to use orchestration engine. The language used to tell Ansible what to do with your infrastructure is in the form of “playbooks” - essentially a YAML file that describes a full workflow of actions Ansible should take.

Playbooks are where the real power of Ansible shines through. Let’s say you have a weekly maintenance window for performing software upgrades on all servers. You probably have an order of operations you want to go in, such as upgrading the web servers first, then DB servers, etc. Each phase will represent an individual “play” in a playbook. You may want to build a play in between upgrade phases to go back in and do some kind of test to ensure the upgrades were successful.

There is a pretty significant use case for this kind of methodology in networking. For instance, it’s simple enough to use Ansible to create a VLAN on all switches (honestly this can be done with a little python/paramiko script) but it is entirely different to build varying configurations for many switches based off of their place and role in the network.

One big difference between Ansible and other tools is that there is no implicit requirement for a local agent on the nodes being configured - the default interaction uses simple SSH, or whatever protocol a given module implements. This is good news for us in networking, as only a small number of switches (such as Cumulus) allow for the installation of any software.

Now - the workflow and user interaction is interesting and very powerful, but somehow the work has to get done….meaning someone has to write software to do things like connecting to a switch and running a command. That is done within Ansible modules. Using modules, someone with no programming experience is able to simply pass parameters to a module using a playbook, and the module will take that information and do something with it. There are a plethora of default modules included with Ansible, but there are also many custom modules out there on the internet for you to use. I’ll be introducing my first two in this post.

Note that because Ansible is primarily used for working with server operating systems, the list of modules is oriented towards that use case. There is a growing number of modules for networking devices, but it is still relatively small. This means that if you can’t accomplish your task using a handful of SSH commands, a custom module is needed. Cisco UCS is a good example of this - administration of UCS is primarily done using the XML API (typically front-ended, of course, by a script or the Java GUI). For the purposes of this example, we’ll be using some modules that I quickly threw together to get this kind of functionality.

I could go on and on, but instead I’ll point you to some stellar Ansible-for-networking posts that have done a fantastic job (and include some interesting use cases themselves):

- Jason Edelman - Ansible for Networking

- Kirk Byers - Network Config Templating using Ansible

- Jeremy Schulman - The VSRX Files Vol 2 - Automation with Ansible

I Hate SAN Zoning - I Love Ansible

I figured I’d just put it out there….I am not a fan of logging into a server platform (commonly UCS for me), looking up all the WWPNs, writing them down, giving them a description, putting them into some kind of zoning configuration, adding targets, logging into a switch, pasting, and hoping I didn’t mess up. And this is all assuming a greenfield build where I don’t have to worry about completely borking an existing SAN.

I realize that there are some methods for mitigating this….many of my colleagues do as I do and just build WWPN pools in UCS that are sequential, so they know which service profiles will get which WWPNs. While this is nice, it’s not good enough. First, it assumes you’re using UCS, and that’s a good assumption for me, but maybe not others. Plus, it also involves a lot of human interaction, and since WWPNs are 64-bit hexadecimal addresses, of which there may be 100 or more in a given system, that’s too much work, and too much risk of error. Call me lazy, but I know low-hanging fruit for automation when I see it.

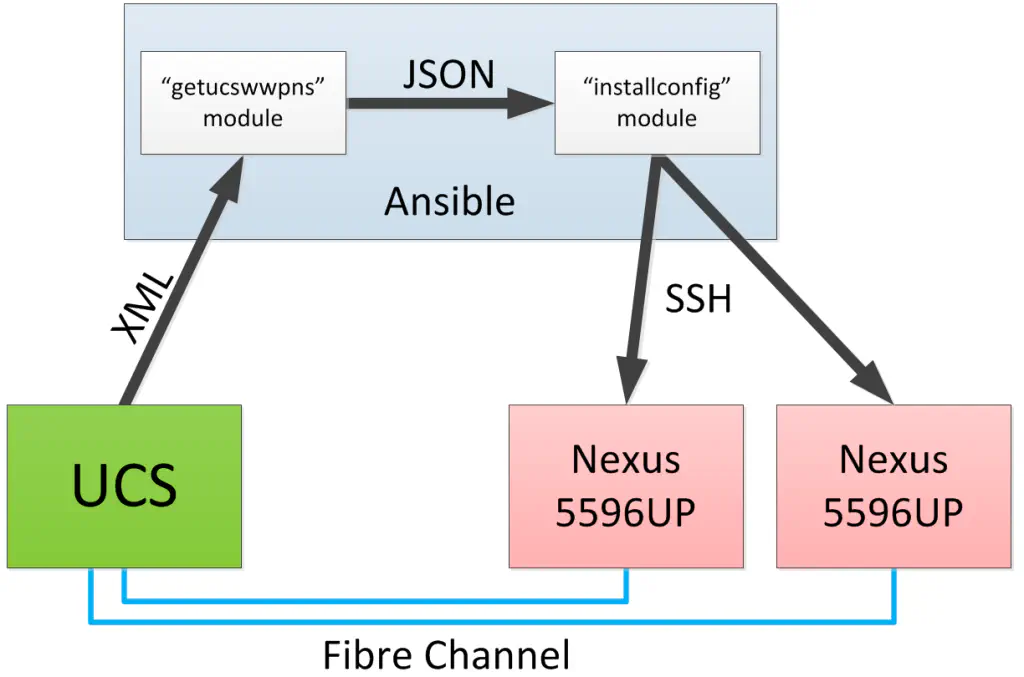

This essentially means that it’s not only the output I wish to automate (again, easy with a simple script) but also the input. Complete end-to-end transfer of configuration data, with human interaction kept to a minimum. I’m using JSON as the means of passing data from the “input engine” to the “output engine”, roles which are fulfilled by my “getucswwpns” and “installconfig” modules, respectively.

This will allow me to develop these modules independently from each other to work better and more fluidly so that they can easily be consumed by Ansible users. For instance, I have no intention of sticking with SSH as a transport to the Nexus switches, I will be moving to some kind of NETCONF implementation shortly. Stay tuned for more information on this, as I’ve already begun work towards this effort.

Now we can start the demonstration. I encourage you to review the basics of Ansible at http://docs.ansible.com, then head over to my Github page where I’ve provided all the files you need to make this happen in your own lab (provided you’re lucky enough to have UCS fabric interconnects and a pair of Nexus 5Ks in your lab). In addition, I’ll be creating a brief walkthrough video that I’ll post at the end of this article.

Note that for this demonstration, you’ll need Ansible (obviously), in addition to Python 2.7, Paramiko, and the UCS Python SDK 0.8 - these versions were what I tested with, other versions may work as well.

Demonstration

TL;DR and summarized demonstration video available at the end of the post.

This demo isn’t about writing Python code/Ansible modules, it’s about using them. So lets take the two that have been written for us by our fearless developer, and ensure Ansible knows about them (I have just been throwing them in /usr/share/ansible - there are a number of directories that qualify).

khalis:library Mierdin$ sudo cp getucswwpns /usr/share/ansible/ && sudo cp installconfig /usr/share/ansible

Next, we need to build an inventory file. This is a way of describing to Ansible the devices we wish to take action against, and some information about them if needed. Here’s what I built:

[ucs]

10.12.0.78

[nexus5k]

10.2.1.54 fabricid=a vsanid=10 targets=50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:01,50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:02

10.2.1.55 fabricid=b vsanid=20 targets=50:00:00:00:00:11:b0:01,50:00:00:00:00:11:b0:02

This is relatively straightforward - this is essentially written like an INI file, in that we have groups of devices that are named. So if I wanted to refer to all UCS devices (there’s only one there, but there could be plural) then I would just use the name “ucs”. Same with our Nexus 5Ks - I could use the group name “nexus5k”. I place these elements directly into the Ansible inventory file located at /etc/ansible/hosts.

You may also wonder what the extra information next to the 5K ip addresses are - those are special variables that we’re going to be able to use when we write our playbook. I created these so we can identify to my custom modules which switch is Fabric A or B, and which VSAN is in use on each switch. Not exactly the most robust configuration (i.e. doesn’t allow multiple VSANs on each switch) but covers about 90% of the installs I run into. In addition, I’m specifying the two target WWPNs that each zone should contain, on each device - in the form of a comma-separated list.

Now it is time to write our playbook. This is where the Ansible user spends much of their time, as it is where all of the workflow intelligence and “input data” goes. Playbooks are written in YAML, which is technically a structured data format, but it’s just about the easiest one to read.

Playbooks can do a LOT. I mean it - this demo will barely scratch the surface of what you can do with a playbook. Not every task involves a module. It’s almost like an English-based scripting language. You should definitely read the docs to find out more.

Three hyphens start our playbook, and a single hyphen starts an individual play. Let’s start by describing the first play:

The “name” parameter is easy - we’re describing what our play is intended to do. The “hosts” argument specifies the inventory group we defined earlier that this play is intended to run on. The “connection: local” notation merely indicates that our playbook should run locally, not on the target device (which in this case obviously would not be possible). Finally, we have “gather_facts” set to “no” for the sole reason that I haven’t implemented this feature yet. Facts are an interesting Ansible concept that I plan to use to help make my modules a little more intelligent about the nodes they’re configuring, but I just haven’t gotten around to it.

Every play has one or more tasks, so let’s define that next:

1 tasks:

2 - name: Pull WWPNs from UCS

3 getucswwpns:

4 host={{ inventory_hostname }}

5 ucs_user="config"

6 ucs_pass="config"

7 outputfile=output.txt

8 logfile=log.txtThis is also very self-explanatory - I’m naming the task according to what it’s designed to do. I also call out the specific module name that this task is intended to run, namely the “getucswwpns” module I created. All of the indented text shown below this module name will represent various arguments that will be passed to this module. As you can see, I need the obvious basics, like the IP address of UCSM, and a username/password. However - the interesting notation next to the “host” argument is actually pretty cool. “inventory_hostname” is a special Ansible variable that represents whatever node that this task is running against. So no matter how many nodes are in the inventory group we’re referring to, this parameter will always equal the current IP addres. This is how we’re able to run a single play against multiple systems. The “outputfile” argument is where our JSON output will be located, and I’m also providing a basic logfile below that.

This is it! This playbook as written will pull WWPNs from a UCS system and place them into a JSON file on our system. Before we go any further, let’s just run this as-is and see what we get.

To run a playbook, simply use the “ansible-playbook” command and specify our .yml file as an argument.

$ sudo ansible-playbook autozone.yml

PLAY [Get Existing UCS Information] *******************************************

TASK: [Pull WWPNs from UCS] ***************************************************

ok: [10.12.0.78]

PLAY RECAP ********************************************************************

10.12.0.78 : ok=1 changed=0 unreachable=0 failed=0

khalis:playbooks Mierdin$

Since we specified a relative path, our output file appears alongside our playbook.

{

"a": {

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:A0:00": "ESXi-01_ESX-VHBA-A",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:A0:01": "ESXi-02_ESX-VHBA-A",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:A0:02": "ESXi-03_ESX-VHBA-A",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:A0:03": "ESXi-04_ESX-VHBA-A",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:A0:04": "ESXi-05_ESX-VHBA-A",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:A0:05": "ESXi-06_ESX-VHBA-A",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:A0:06": "ESXi-07_ESX-VHBA-A"

},

"b": {

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:B0:00": "ESXi-01_ESX-VHBA-B",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:B0:01": "ESXi-02_ESX-VHBA-B",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:B0:02": "ESXi-03_ESX-VHBA-B",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:B0:03": "ESXi-04_ESX-VHBA-B",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:B0:04": "ESXi-05_ESX-VHBA-B",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:B0:05": "ESXi-06_ESX-VHBA-B",

"20:00:00:25:B5:21:B0:06": "ESXi-07_ESX-VHBA-B"

}

}

This is nicely formatted JSON that has organized everything into neat key:value pairs, in addition to separating out the “a” side from the “b” side. This is useful for ensuring our WWPNs only get placed in switch configurations where they will be seen, and therefore, be relevant.

Okay, so this is all well and good, but if I’m going to make this at all useful, I need my playbook to take this information and script out a configuration for me. This is where the second module that I wrote - “installconfig” - comes in. I know the name sucks, but as I mentioned, this is an example only. I am building a more formal Ansible module for doing all kinds of NXOS configuration in a separate project.

If this module were also designed to run against the same “ucs” inventory group, we could have gotten away with a single play that contained two tasks - but instead, we need to build a completely separate play in our playbook file:

1 - name: Perform SAN Configuration

2 hosts: nexus5k

3 connection: local

4 gather_facts: no

5

6 tasks:

7 - name: Push configuration to Nexus switches via SSH

8 installconfig:

9 host={{ inventory_hostname }}

10 n5k_user="admin"

11 n5k_pass="Cisco.com"

12 fabric_id={{ fabricid }}

13 vsan_id={{ vsanid }}

14 fc_targets={{ targets }}

15 inputfile=output.txt

16 logfile=log.txtThis is much the same as our first play, with a few exceptions. Obviously we’re running against the “nexus5k” inventory group as stated above. Also, the “installconfig” module requires a few extra arguments. You’ll notice the two arguments “fabric_id” and “vsan_id”. These are where those inventory variables we set earlier come in handy. For instance, one of the 5Ks was written like so in our inventory file:

10.2.1.54 fabricid=a vsanid=10 targets=50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:01,50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:02

Just like the special “inventory_hostname” variable, these will get populated for each node this module runs on. My module is designed to take in this information and change the configuration appropriately.

Now - though an analysis of how my module is written is beyond the scope of this article, I’d like to call out that I’m using a Jinja2 template for most of the legwork in creating a configuration snippet, available within the “templates” folder of my demo:

{% raw >}} device-alias database {% for wwpn, name in initDict|dictsort ->}} device-alias name {{ name }} pwwn {{ wwpn }} {% endfor >}} device-alias commit

vsan database

vsan {{ vsan }} name VSAN_{{ vsan }}

!ZONING CONFIG

{# TODO: Need to allow vsan ID to be dynamic as well #}

{% for wwpn, name in initDict|dictsort >}}

zone name {{ name }}_TO_NETAPP vsan {{ vsan }}

member pwwn {{ wwpn }}

{% for wwpn in targets ->}}

member pwwn {{ wwpn }}

{% endfor >}}

{% endfor >}}

zoneset name ZONESET_VSAN_{{ vsan }} vsan {{ vsan }}

{%- for wwpn, name in initDict|dictsort >}}

member {{ name }}_TO_NETAPP

{%- endfor >}}

zoneset activate name ZONESET_VSAN_{{ vsan }} vsan {{ vsan }}

{% endraw >}}

If you’re interested in how this is used in this context, my earlier post may be of interest to you.

Our end-to-end playbook is now finished, and it is glorious (completed version here). If we run it now, the “getucswwpns” module will run once more, grab a fresh copy of all of the UCS vHBA/WWPN information, and write it to a JSON file on our filesystem. Then the “installconfig” module will immediately read this file, and using the Jinja2 template, generate a full configuration snippet that includes zoning, aliases, and then some. Just about everything in a FC configuration that is considered “tedious”. It will then iterate through that snippet, and write every line to an SSH session to the correct switch. The user needs only run this playbook - not log into a single UCS Manager, or Nexus 5K.

If you take a look at the logs, you can see the configuration that the second module created and pushed to the switch. Here’s the “A” side configuration as an example:

vsan database

vsan 10 name "VSAN_10"

device-alias database

device-alias name ESXi-01_ESX-VHBA-A pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:00

device-alias name ESXi-02_ESX-VHBA-A pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:01

device-alias name ESXi-03_ESX-VHBA-A pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:02

device-alias name ESXi-04_ESX-VHBA-A pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:03

device-alias name ESXi-05_ESX-VHBA-A pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:04

device-alias name ESXi-06_ESX-VHBA-A pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:05

device-alias name ESXi-07_ESX-VHBA-A pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:06

device-alias commit

zone name ESXi-01_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP vsan 10

member pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:00

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:01

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:02

zone name ESXi-02_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP vsan 10

member pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:01

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:01

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:02

zone name ESXi-03_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP vsan 10

member pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:02

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:01

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:02

zone name ESXi-04_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP vsan 10

member pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:03

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:01

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:02

zone name ESXi-05_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP vsan 10

member pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:04

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:01

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:02

zone name ESXi-06_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP vsan 10

member pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:05

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:01

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:02

zone name ESXi-07_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP vsan 10

member pwwn 20:00:00:25:b5:21:a0:06

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:01

member pwwn 50:00:00:00:00:11:a0:02

zoneset name ZONESET_VSAN_10 vsan 10

member ESXi-01_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP

member ESXi-02_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP

member ESXi-03_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP

member ESXi-04_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP

member ESXi-05_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP

member ESXi-06_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP

member ESXi-07_ESX-VHBA-A_TO_NETAPP

zoneset activate name ZONESET_VSAN_10 vsan 10

That’s pretty cool. And this is pretty small-scale too. Imagine if there were 100+ hosts instead of 7. Imagine if other zoning practices were used - like 1:1 zoning, meaning that each initiator to target relationship required a completely separate zone. This method ensures consistency, it is quick, and it STILL requires no knowledge of how to write code. Only how to write a simple Ansible playbook.

Conclusion

Just to get some gears moving, there are plenty of other things that these modules (or similar ones) could do that this demo didn’t quite address:

I am statically setting the target WWPNs in the playbook arguments for the time being. It would be fairly straightforward to write a third module that reaches into the storage array, and grabs the actual targets, in much the same way we’re retrieving WWPNs from UCS in the first module.

By no means does the JSON file provided by our first module HAVE to be used by the second module. It’s plain old JSON, so another module could be written to consume the same file as well. Perhaps automatic documentation generation - or perhaps entry into a CMDB?

3. Neither of these modules are part of any of my "long-term" Ansible plans - just example modules that fit a niche. I will be developing more full-featured modules for both UCS and NX-OS that will be far more comprehensive - including this use case, but also many many others.

I hope this demo was able to shine a little light into a promising area of infrastructure automation. Again, please find all files referenced here on my github project so that you can try this out for yourself. Finally, I’ve created a relatively short video that shows this demo in action. Enjoy!