The Learning Curve: Implementations vs Fundamentals

April 8, 2014 in Systems5 minutes

I’ve spent a lot of time lately considering skillsets, and how people go about learning new things. Many aspects of the IT industry are starting to overlap with each other (the idea of DevOps being just one manifestation) and it’s incredibly interesting to see how individual professionals are incorporating new knowledge into their repertoire. I did a little contemplation on this over the weekend and I’d like to share some observations I’ve made.

Let’s say you’re an up-and-coming network engineer. You have heard that the networking industry is a growing field with lots of promise for those that like to learn new things. As you enter the field and begin to learn new things, you very quickly pick up on the “fundamentals”. You begin to learn the answers to questions like “What is IP used for?”, “Why do we need Spanning Tree?”, “What does a firewall do?”.

In this context, the “fundamentals” are ideas and concepts that serve as the building blocks of all networks, and are not specific to any one vendor. Surely there are a multitude of concepts that fit this description, but it is a finite list. Eventually one must begin to focus on specific implementations of a technology, and begin to put the concepts to use.

This isn’t a black and white transition either. After a while, it becomes difficult to keep talking about fundamentals without a certain amount of focus on a specific implementation. In networking, we generally claim the CCNA to be the “de-facto” networking certification primarily because the coursework heavily focuses on fundamental concepts like the OSI model, but it of course requires the learner to memorize Cisco CLI commands in the process.

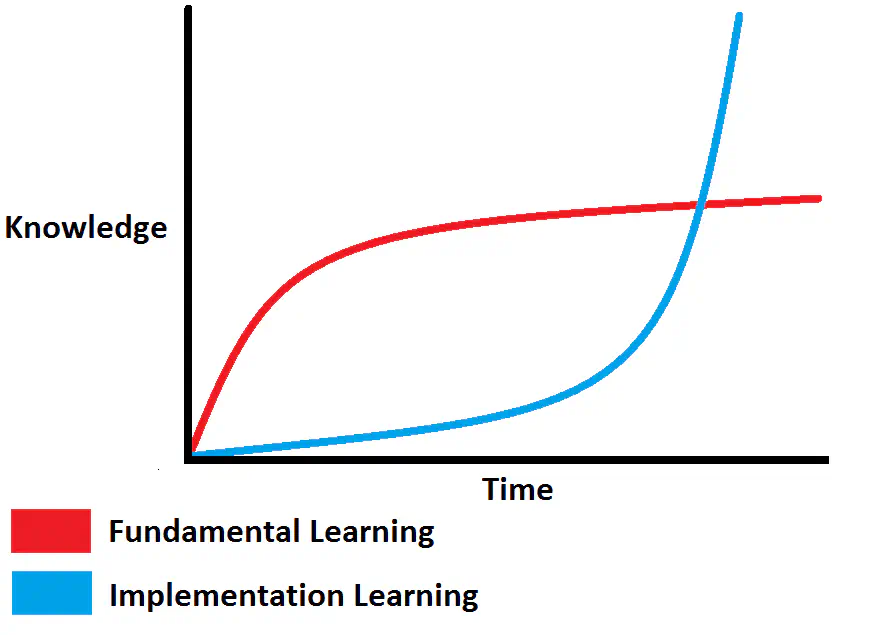

As the learning continues into more advanced topics, and the learner gains more experience, eventually the ratio between “fundamentals” and implementation-specific knowledge flips on it’s head. The amount of focus applied towards learning implementation details - perhaps a different vendor’s CLI syntax for already learned concepts - increases exponentially, while the amount of focus on fundamentals - out of necessity - tapers off, forming more of a logarithmic curve.

This is certainly true when you begin to learn a different implementation - many of the fundamental concepts in networking are transferable between vendor platforms, but of course the CLI commands used are different.

Learning to write software is very similar, (as is many other aspects of IT). Early on, you learn about loops, “if” statements, classes, methods, etc. Of course it becomes very dry if you use nothing but pseudocode, so it’s usually best to use something easy like Python to see these concepts in action. Again, there’s only so much learning you can do on these fundamental concepts, and the ratio between fundamentals and implementation flips, and you feel compelled to learn other languages.

Now, we could talk about how many aspects of life trend in this direction, but I think it’s important as technologists to look at the intersection of software with infrastructure. The idea of cloud computing has really forced these two areas together, and there are lessons to be learned for those either completely new to the industry, or that are trying to adopt a new skillset.

Learning: Changing Gears

Assuming my theories are reasonably accurate, the learner must face a choice:

Continue to move forward in the current topic of choice, exploring more and more implementation details, and though scarce - likely picking up a few more fundamental concepts along the way.

Accept the current level of implementation knowledge and move into a different knowledge area.

It is totally and absolutely up to the individual to choose which path is right for them. Some find greater satisfaction in exploring a specific area more completely - while others either want or need to be able to speak to multiple technical disciplines. I have personally chosen option 2 on multiple occasions for similar reasons.

In the paradigm I’ve illustrated, a small but rapidly growing group of network engineers are also choosing option 2 right now. They’ve been told to “learn Python” so they’re putting down the networking books (even if just for a short time) and picking up a Python book.

As you might imagine, Python is a single implementation. While it is true that Python is likely one of the best languages for new programmers to learn due to it’s simplicity, “learning Python” is hardly the goal here - just a really good tool for getting there.

While this is certainly a viable path for many, I’ll just mention that it is of equal or greater importance to apply focus on the “fundamentals”. Sure, this includes programming constructs like loops, methods, conditionals, but it also includes basic software development concepts like how services are created and consumed. How about methodologies like continuous delivery, or agile?

These reflect a cultural adoption more than simply a technological one - and there are plenty of interesting lessons to be learned from the software industry. Can you imagine an enterprise networking team with the tools and expertise mature enough to offer a single programmatic interface to making infrastructure changes?

Conclusion

These are just my own personal observations and I offer this article mostly for the simple reasons that I find the parallels between areas of our industry - areas that have long been considered to be quite different - to be extremely fascinating.

My advice to those infrastructure-focused folks: undoubtedly you’ve heard that “learning to code” is going to be important in the next coming years in order to stay relevant. This is a very specific statement trying to answer a very broad question, in my opinion, and while it represents a path that some will take, it’s hardly the entire point.

I believe that if you instead focus on the “why” behind this kind of advice, you’ll be much better off. What is it about the networking industry that makes others believe it has “fallen behind” other technical disciplines? How can I offer a consumable service to other technology disciplines while maintaining uptime and scalability, and not requiring everyone to know how packets go? The answers to many of these questions will likely require some out-of-the-box thinking, and in many ways, a return to the fundamentals - even if those fundamentals have nothing to do with technology.