The Evolution of Network Programmability

May 27, 2014 in Systems16 minutes

This post is the “text” version of a talk I gave at Cisco Live US 2014 titled “SDN: People, Process, and Evolution”. While there is certainly some technical details involved here, this topic is really more of a philosophical one, and it is very near and dear to my heart as I talk with more folks about how networking is going to evolve in the years to come.

The Problem with Networking

Most of my readers would consider themselves network engineers - folks that live and breathe networking and everything that’s required to build them. Folks like you and I don’t really need to hear what’s wrong with networking, as we live it every day. However, for the sake of others that may be reading, let me provide a little context here.

Nearly everyone in the industry is hearing about how “networking is slow” with respect to provisioning time. We hear about how virtual machines can be instantiated in a few seconds (hell, application containers can be spun up in less than a second!) yet the really important network stuff like firewall or load balancer policies take forever. They’re not wrong - networking has never really been tightly coupled with compute and storage policies, and much if not all network provisioning processes in the average IT shop is performed manually.

Why is this? It might seem like network engineers are just trying to torture anyone who wants to get connectivity, but the reality is a little more complicated. I’ve seen a lot of environments where the network teams and server or app teams are literally hostile towards each other, but in almost every case, I was able to trace this behavior back to the fact that IT leadership places an unyielding burden on the network team to maintain uptime at any cost.

I haven’t been working in this industry for that long, but even so, I’ve already personally experienced instances where automated practices were actively fought against because they represented unacceptable risk to network infrastructure. I’m not even talking about anything extravagant, even simple stuff like VLAN changes. Our change management model just doesn’t allow for it right now. It’s not that we don’t want to make networking as agile as compute has become - it’s because of networking’s place in the IT discipline as “that thing everything depends on” that has passed down this stagnant culture.

This has produced what I’m calling a “box mentality”.

The Box Mentality

Let’s imagine for a second that you have been charged with making a change on your company’s network. You’re bringing up a new application, which requires an end-to-end configuration of a new QoS class across the board. You go through all the configuration requirements on the various devices that will be impacted by this change. You allocate a new tag for this traffic to be marked with. You create policies to recognize this tag and do various things with it, such as dedicating bandwidth in the event of congestion.

This forms your overall design for this change. It’s pretty slick when completed. You don’t think in terms of individual routers along the path in this phase, you think of the overall design network-wide.

Then, the rubber meets the road. Either you or a more junior engineer will be required to actually make these changes. Regardless of who makes the change, or what role they played in the design phase, at some point you have to log in to a device. When you’re looking at routers R1 through R10, and you need to make a change on R6, you make a translation in your head for what commands you need to type into R6 to fit into the overall design.

That conversion, which takes place purely in your cranium, is The Box Mentality. It’s the idea that even though we’re smart network engineers that put together amazing data networks that work really well, we still have to address the network node by node. Our design describes the intent of what we want to do, but the conversion of intent to implementation must take place in a human mind, on a per-box basis.

This is somewhat less of an issue with really small organizations. Even basic non-technical practices like maintaining clean configurations and using a standard build or change process can help ease the pain. However, this per-box behavior doesn’t scale very well. Eventually all of the extra “garbage” configuration stuff will pile up, and really smart network engineers will very quickly spend most or all of their time writing change requests and making simple VLAN adjustments. We’re no longer able to get out in front of our network design - instead, we’re fighting fires.

We need a new model. We need to put into place a methodology that allows us to interact with the network in the same way that we design it. We need to figure out how to tap into the massive resource that is our years of experience building networks, and not have it bottle-necked by ancient configuration practices. The idea of Network Programmability is a great way to get there. It’s not a replacement of networking skills. Actually quite the opposite - it is a way to complement existing networking skills, one that actually makes a solid understanding of data networking more important.

The Pyramid of Network Programmability

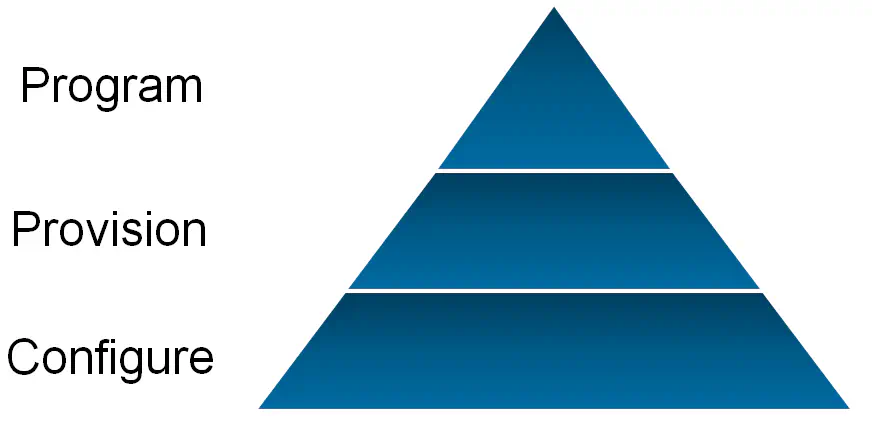

Now - I give you the pyramid that will serve as our visual through the evolutionary path that is network programmability.

Our evolution will start at the bottom, with the “Configured Network”, and move up from there. First, a few things about this pyramid:

The lower layers are not “bad” or “less important” than the higher layers. Like the food pyramid, the lower layers are in many ways the most important….they are the foundation to all of the other stuff on top.

Our goal is to have the entire pyramid, not just the top or bottom, even if the top is getting a lot of press right now.

Purchasing products or building solutions that do the stuff on top, without a mastery of what’s on the bottom, or working with those that know it well, will inevitably result in failure.

Keep these points in mind as you read through the three phases of network programmability below:

Phase 1 - The Configured Network

This phase should not be foreign to anyone. The activities that take place in this phase are synonymous with what takes places in the Box Mentality.

This is an interesting phase, because in the context of network programmablity, on the surface it doesn’t seem to do much for us. We’ve been doing this forever, right? It’s boring - configuring a router doesn’t get all the news articles and tweets, right?

However, consider how the internet was formed. It is out of necessity, and the knowledge that “my router will have to talk to your router somehow” that we birthed protocols like TCP/IP, IPv6, Ethernet, BGP and many more. We knew there would have to be some kind of standardized form of communication that everyone’s device can use.

These protocols didn’t go away - we’ve used them ever since, adding to them as needs arose. What’s most interesting is that many of the cool projects going on in the SDN space actually re-use protocols like these, but in unique ways. This trend tells me that the most successful strategy for attaining network programmability isn’t to re-invent the wheel, but to first obtain a complete mastery of the basic building blocks of networking itself. Understanding IP and TCP may only have a brief mention in a low-level certification, but in my experience, truly mastering these protocols will only set you up for greater success in learning higher-level functionality.

The same is true for being able to build more advanced provisioning and configuration tooling into your network.

All of this is why Phase 1 is the bottom part of our pyramid. If you aren’t mastering what made the internet happen, you’re only setting yourself up for failure when you tackle cool stuff like DevOps, and SDN.

Phase 2 - The Provisioned Network

As important as Phase 1 is, it’s not the total picture. Relying on existing, manual processes will eventually cause you to hit a bottleneck. For many organizations, these bottlenecks have already occurred, and the business has simply become used to it. The same was true for compute provisioning prior to virtualization. It was simply a generally accepted fact that applications would take weeks to bring online, since hardware procurement was always part of the process.

Along came server virtualization, and though consolidation was low-hanging fruit, we quickly realized all of the cool things you can do with virtual machines when they’re not tied to a physical device. Provisioning a new application went from weeks to days, then from days to hours, and hours to minutes, as we built additional functionality on top of this model.

It wasn’t an easy journey - there was a LOT of FUD around server virtualization - some said it was slow, had lots of overhead, and risky (because of the consolidation of workloads onto “single points of failure”) - the list goes on. Eventually, the business realized that the technology was mature enough, and with appropriate process to reflect the new way we did compute in the data center, virtualization was here to stay. The culture of the organization was radically altered to take advantage of these improvements.

This ingrained culture and insistence on manual process is what Phase 2 intends to change within the networking industry.

At scale, repetitive tasks are the not-so-silent killer. Adding a VLAN on a few dozen switches, updating an SNMP community string, or more complicated stuff like bringing up a remote site, all are tasks that we do somewhat often in many organizations. These repetitive tasks tend to occupy a lot of time, mostly for those whose time is really valuable.

These tasks are prime candidates for automation. This is an important phase on our pyramid because it is not a pie-in-the-sky idea. Very simple, existing frameworks can be used to make this happen. As I wrote before, this is all about culture - allowing the business to see that network automation can be done in a responsible way, so that the benefits are even clearer. So this phase is all about baby steps. It’s all about slowly pushing more and more automation into your organization’s operations model, not just for the sake of automation, but to allow the business to become accustomed to doing it the right way.

I wrote before about using Jinja2 and a VERY small amount of Python to generate some standard build processes around network configuration. This is a fairly easy way to start a part of Phase 2 that is extremely crucial - the standard build process. An organization-wide, standardized way of producing new configuration. This Jinja2 template is a great example of what you can do with very basic knowledge of general code constructs.

{% raw >}} {% for int in pints >}} interface Ethernet{{ int.slotid }}/{{ int.portid }} description {{ int.description }} switchport mode {{ int.switchportMode }} {% if int.switchportMode == “trunk” ->}} switchport trunk allowed vlan {{ int.allowedVlans }} {%- else >}} switchport access vlan {{ int.accessVlan }} {%- endif >}} {%- if not int.channelGroup == 0 ->}} channel-group {{ int.channelGroup }} mode active {% endif >}} {% endfor >}} {% endraw >}}

So that’s great, but it still requires a little code knowledge to really do well, right? Well there’s been quite a bit of attention around automation frameworks like Puppet, that allow you to make use of automation without knowing any code at all. My favorite framework is Ansible, and there has already been quite a bit of buzz regarding the use of Ansible for all kinds of infrastructure automation.

Templates like the one shown above serve as a fundamental building block of many existing automation toolkits like Ansible that are all aimed at doing more without becoming a full-blown developer.

Phase 3 - The Programmed Network

Lots of folks like to talk about SDN and Network Automation like they’re the same thing. Admittedly, they’re similar on the surface, but only because network automation (phase 2) is such a crucial building block of what SDN will likely turn out to be in the next few years. In reality, the two ideas are quite different, but related in a pre-requisite kind of way.

In order to clarify this, I like to bring up a specific example - the concept of a vSwitch. My first experience with a vSwitch, like many of yours, was VMware’s Standard vSwitch, baked into every ESXi hypervisor out there. Simply put, it connects our virtual machines into the physical network. Now - many vSwitches work in the same way, but this vSwitch does not act like a physical switch. A physical switch takes Ethernet frames into a port, learns the MAC address of that frame based on it’s source address field, and then creates a table entry that matches that address to that interface. All frames destined for that address from then on out, will be forwarded to that port.

The vSwitch works a little differently. Whenever a virtual machine is created, the MAC address for the vNIC on that VM is already known to the hypervisor. It was actually provisioned by the hypervisor. The vSwitch is just an extension of the hypervisor - the vNIC, the vSwitch, and the “vCable” are all maintained within server RAM. So - no learning needs to take place - the MAC addresses are simply known to the vSwitch upon instantiation.

Now - there is a big difference between a single vSwitch inside a server and accomplishing the similar traits on a large physical network, so lets dig in a little more.

SDN has undergone a LOT of changes in the past few years, and will continue to do so for years more. However, I believe that this idea of proactively pushing network policy is an idea that will persist and win out. There are a few benefits to this approach, as well as a few clarifications I’d like to make.

First - a centralized control plane (i.e. OpenFlow) is an interesting concept but carries significant hurdles. In order to really make the best of a protocol like OpenFlow, it must be used in very specific ways. One approach is to limit the scope of OpenFlow domains and federate between then using MP-BGP. In this case, BGP would communicate all the state information regarding L2 or L3 among all of the control domains.

OpenFlow was immediately disruptive to the networking industry because it was so new, so revolutionary, that everyone started thinking of new ways to use it, and very quickly, SDN equaled OpenFlow.

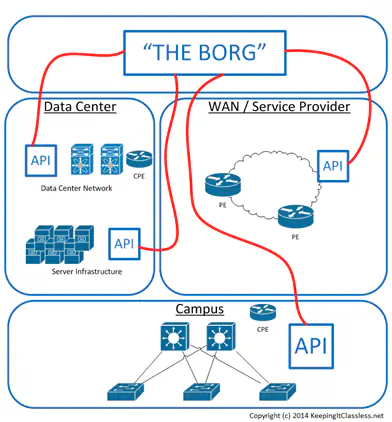

So…looking past the history lesson and to the future of what network programmability will look like, I think that some kind of centralization will win out. In reality, control plane/data plane separation will likely play a role in the SDN world, but it will be one of many implementation details to choose from - not the whole picture.

So, putting the control plane discussion to the side for a moment, some kind of centralization will play a critical role, just as it did with server virtualization.

Right now, we create AND apply new policy in a distributed fashion - the “box” mentality. In the “programmed” network, we will create and apply policy centrally, and rely on software to figure out how best to apply that policy to each box. The translation I mentioned in the very first section - one that currently takes place in our minds - will take place in software. Some higher entity that has the same view of the network that we as humans have, and is able to make sense of the knowledge you impart into it as a seasoned network engineer.

Certainly more to come in this space - this is a big reason why I’m talking at such length regarding phases 1 and 2….they are very crucial, and very NOW.

Do I Need to Become a Programmer?

Hopefully by now you realize that “network programmability” doesn’t really have anything to do with being a programmer. This confusion is where the question “Do I need to be a programmer to be relevant in networking?” seems to originate in many cases.

The answer to the question as stated, is a resounding “no”. However, there is still room for folks in this space to learn code. In my opinion, the network professionals of tomorrow will fall under one of two categories.

The first is a network engineer that knows protocols VERY well, not just their configuration details. They know how to think like a programmer, with respect to concepts like DRY (don’t repeat yourself) - service-oriented architecture, and the consumption model. This network engineer is not far off from those that exist today in terms of networking knowledge, but with a focus on the protocols themselves, not just the commands required to enable them. This network engineer seeks out tools to help automate the provisioning of network resources, and strives to use these tools to make the network more consumable to other disciplines.

The second is a network engineer that - if for no other reason - writes code because they truly want to, not because they feel like they have to. This is likely someone with an existing development background, and enough background in networking to understand which tools need to be created. This engineer will spend time working with open source and DevOps communities working on behalf of the networking industry to create better tools well-suited for network tasks. This person will hold the crucial role of advocating between the software and networking worlds, to make both better from each other. This person does not know how to spell the word “silo”.

I believe that the vast majority of folks will fall under the first category, and this will serve the industry best. The truth is that we don’t need all network engineers to learn code. We need network engineers to solve networking problems. We also need a smaller subset of these folks to tackle the problems in existing tool sets and getting the networking discipline to understand how to improve processes for the better.

Conclusion

Don’t be afraid to challenge the idea that “manual provisioning is just how we’ve always done it”. Ensure that in your ongoing studies that you spend a little extra time reading the RFC for that protocol you’re learning to know how it actually works - you never know when you’ll have to make something work between vendors, where this knowledge is most critical.

The future is bright for anyone that implements frankly any part of what I’m talking about above. There are plenty of complicated problems in networking that some of the cool stuff we’re hearing about promises to solve, but lets not forget about the simpler problems that still exist for many of us.

Are there areas of your business where you feel like automation is just too risky? Have you attempted to implement some of these ideas, but encountered resistance from your organizations’ leadership? I encourage a lively discussion about these ideas - feel free to comment below and let me know what you think!