[SDN Protocols] Part 1 - OpenFlow Basics

July 21, 2014 in Systems6 minutes

Let’s get into our first topic. And what better place to start than with the protocol that arguably started the SDN madness that we’re experiencing today - OpenFlow! I got fairly carried away with writing about this protocol, and understandably so - this is a complicated topic.

That’s why I’ve split this post (which is already part of a series - very meta, much deep) into two parts. This post - Part 1 - will address OpenFlow’s mid to high-level concepts, exploring what it does, why/how the idea of control plane abstraction may be useful, and some details on how hardware interaction works. The second post - Part 2 - will dive a little deeper into the operation of OpenFlow on supporting physical and virtual switches, and the differences in some popular implementations of OpenFlow.

The State of Modern Control Planes

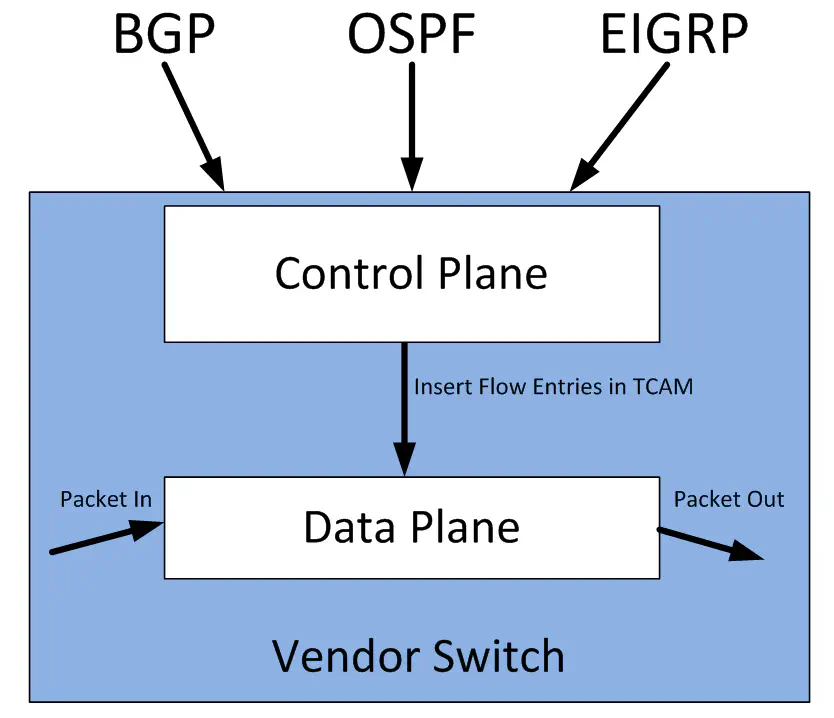

Before we get into the specifics of OpenFlow, it’s important we address the relationship between the control plane and the data plane, and how OpenFlow changes this relationship. You’ve undoubtedly heard by now that one of SDN’s key traits is the “separation” or “abstraction” of the control plane from the data plane. I believe SDN is much more than this these days, but it remains to be a popular trait, undoubtedly driven in large part by OpenFlow itself.

Today’s typical enterprise network devices have a controlling element and forwarding element within the same box. The forwarding element is responsible for taking packets in, doing something with them, and forwarding them back out. It’s all about getting the packet where it needs to go. We call this the “data plane”. The data plane is where you’ll find hardware like the Broadcom Trident II, which is a very popular chip used for forwarding network traffic. Many vendors are beginning to use this chip in their switches, though many vendors are still opting to make their own ASICs, or do both.

The data plane doesn’t make decisions about how to forward traffic, it receives those decisions from the control plane. The control plane is typically a collection of software local to a router or switch that programs flows (rule sets that identify some kind of traffic, and decide what to do with it) into the data plane, so the data plane knows how to do it’s job.

Note in the diagram above, the control plane interacts directly with the data plane to implement these flows in the ASIC’s hardware. The “language” used to program these flows varies based on the vendor - certainly proprietary ASICs have their own flow-programming language that is private to that vendor. However, even “merchant silicon” ASICs like Broadcom’s Trident II do not have a generally published SDK. So, the operation of programming flows directly into switch hardware is handled only by the switch manufacturer.

Of course, networks are not usually made of one box, so we invented protocols like BGP and OSPF that allow boxes - even from different vendors - to share control plane information with each other. One router receives reachability information for a network via BGP, and then programs it’s own data plane so that packets go in the right direction based off of the learned information. This is how the internet was born - forwarding devices making forwarding decisions using locally-resident software, but based off of protocols used to communicate with other routers in the network. This is nothing new.

OpenFlow as an API

These days, we have some programmatic interfaces (APIs) to existing network equipment. Many vendors have implemented their own XML or JSON API that allows you to make network configurations remotely using a language like Python. Arista’s eAPI and Cisco’s NX-API are examples of this.

Some decided that it would be useful to instead define a standardized configuration API so that the common stuff doesn’t have to get re-written - all vendors would need to do is implement a specific schema within such a protocol to make it work with their configuration structures. NETCONF and OVSDB are good examples of this.

OpenFlow should be thought of as another attempt at a standardized API - a programmatic interface that can be used by all vendors. However, where other APIs like NETCONF focused on the configuration of the device, OpenFlow intends to provide access to the data plane itself. It does this by specifying a language that a switch can recognize and use in lieu of making it’s own rules through a local control plane. OpenFlow is a language for generically defining characteristics of a particular flow of traffic (for instance, all traffic from a certain IP address and using a certain TCP port), and what to do with traffic that matches such characteristics.

OpenFlow as a Control Plane

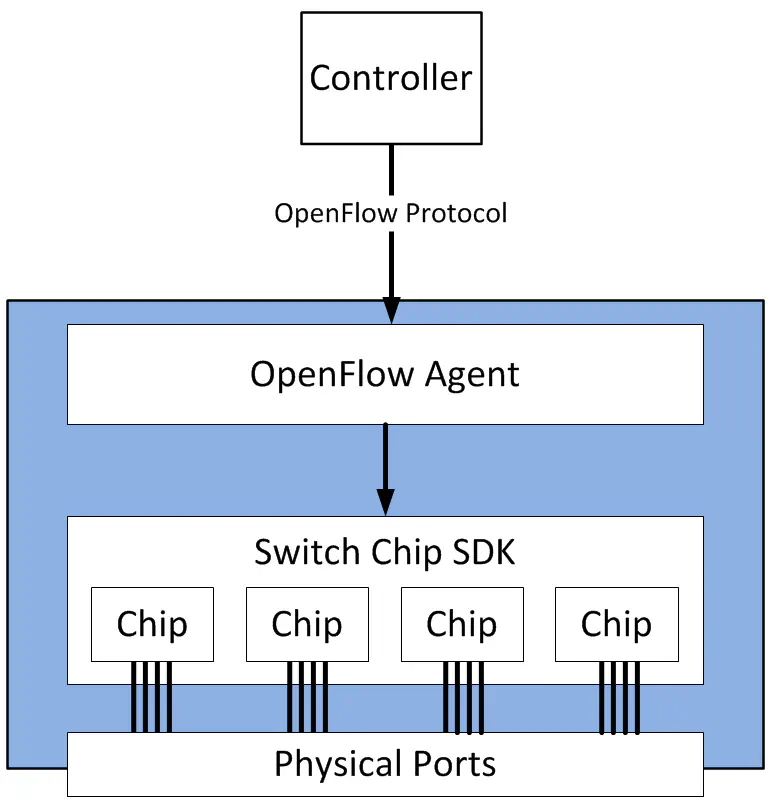

The mechanisms used to program flows into switch hardware vary greatly depending on the hardware involved. OpenFlow is not intended to program flows into them all. Instead, OpenFlow provides a way to describe desired flow state within an agent running locally on the forwarding device. The OpenFlow specification also includes ways for a remote controller to make modifications to this information - for instance, to change a security rule.

This agent, armed with the flow information programmed into it by a controller, acts like the control plane in the first diagram. Unlike the control plane in the first diagram, it doesn’t run routing protocols, or make decisions locally - the controller has already done all that. So, the local agent must store these OpenFlow entries, and push them into the vendor-specific pipeline on that device.

An example flow/action pair - described in english - might be something like:

whenever you receive a frame with ethertype 0x86DD and an IPv6 source address of 2001:db8::1 and a TCP port of 80, decrement the TTL, replace the L2 address information, and forward out port 2. Also copy to port 3.

This is a reasonably comprehensive example of routing an IPv6 packet, but instead of identifying a forwarding behavior based on destination IPv6 address like we do today, this flow uses typically unused fields like the ethertype field in the L2 header, or the destination TCP port.

In addition, I also performed a port-mirroring action for this flow to port 3 as part of this rule. This is the literal nature of OpenFlow - or flow-based forwarding in general. What makes OpenFlow unique is that we now have the ability to define these in a very granular way, while still not diving deep into the specifics of the hardware.

This is why it is up to the vendor of the networking device to implement OpenFlow, since the translation to specific ASIC instructions is typically a proprietary process.

For this reason, features made available by OpenFlow don’t always match up perfectly with the available features for the hardware platform. Every ASIC has it’s own unique capabilities that another ASIC doesn’t share, and vice versa. More on that in the second part of my coverage of OpenFlow.

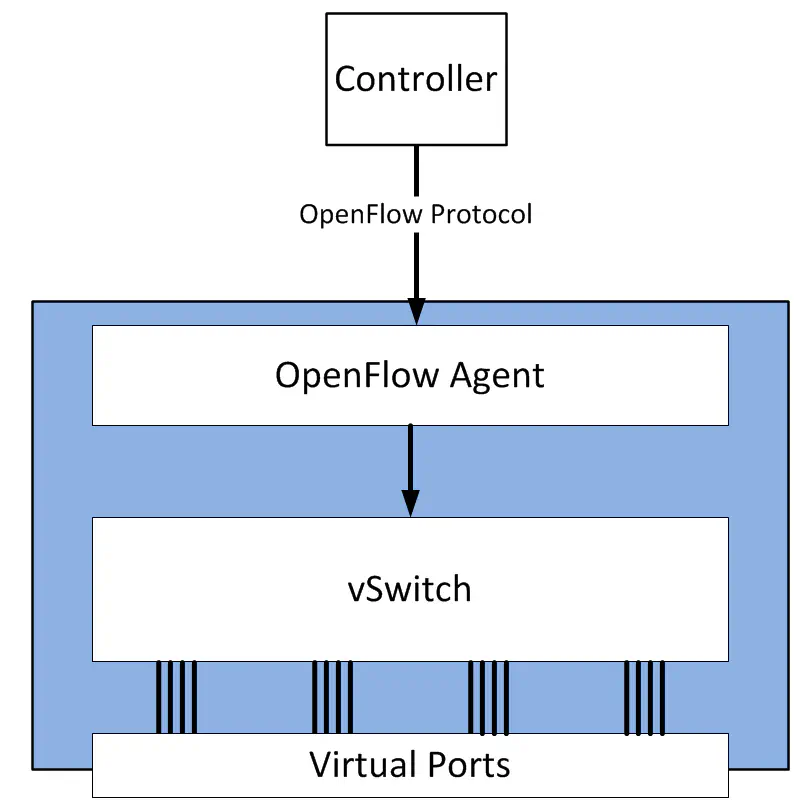

This isn’t specific to physical networking gear either. One of the most popular and active implementations of OpenFlow is Open vSwitch, which works in much the same way - a local process handles OpenFlow messages, runs all necessary tables locally, and interprets them into forwarding actions that the OVS kernel module can understand.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed my introduction to OpenFlow. My purpose here was to introduce those new to the concept at a 50,000’ view. There’s a lot that goes on under the covers, which I’ll be exploring in part 2. (See table of contents at the top of this post) There,I’ll discuss in detail the various components of an OpenFlow architecture within a forwarding device.