What is Unidirectional Automation?

July 9, 2014 in Systems6 minutes

I was pleased as punch to wake up the other day and read Marten Terpstra’s blog post on getting over the fear of using automation to make changes on our network infrastructure. He illuminated a popular excuse that I’ve heard myself on multiple occasions - that automation is great for things like threshold alarms, or pointing out the percieved root cause of a problem, but not actually fixing the problem. The idea is that the problems that occur on a regular basis, or even performing configuration changes in the first place - is a specialized task that a warm-blooded human being absolutely, no-doubt must take total control of in order to be successful.!

With the right implementation, this idea is, of course, rubbish. I asked a question on Twitter not too long ago in preparation for a presentation I was about to give. I have a decent amount of experience working with VMware vSphere, and knew there were some experienced server virtualization folks following me, so I asked about a feature that was thought of in similar light not too long ago:

For those running vSphere, do you have DRS enabled and set to something other than manual? If not, why not? Trying to do a quick poll.

— Matt Oswalt (@Mierdin) June 24, 2014From my own experiences, a feature like DRS was thought of in a similar way. Most folks I saw enable it when it first became a thing would keep it in manual mode, meaning vCenter would advise if there was an imbalance in resource utilization across a cluster, but not actually take steps to fix the issue. Today, we’re more comfortable with DRS because we’ve seen it implemented in a more automated mode enough times to realize it’s not that bad. But back in the day, it was difficult for folks to feel comfortable turning that puppy on Full in production, even though they themselves had tested individual vMotions before.

The responses to my question were as you’d expect. Read the thread for all the responses, but the one that sums it up for me is this one:

@Mierdin I think the real question is who uses manual and why? Can only think of a few cases where it’s not on some level of automatic.

— Michael Stanclift (@vmstan) June 25, 2014Unidirectional Automation

So….“unidirectional automation”. I’ve been using the term a lot lately, and I figured it was high time I gave it a proper definition.

We’re doing a surprising amount of automation as a networking industry today (depending on your definition). The one use case that keeps being brought up to me is the mere fact that most network engineers have created some kind of one-off tool to create a network configuration from something like a spreadsheet. It’s faster and arguably less prone to typos than manually creating a config from scratch, so who am I to say that’s not automation? I’m sure you can think of a similar use case in your environment.

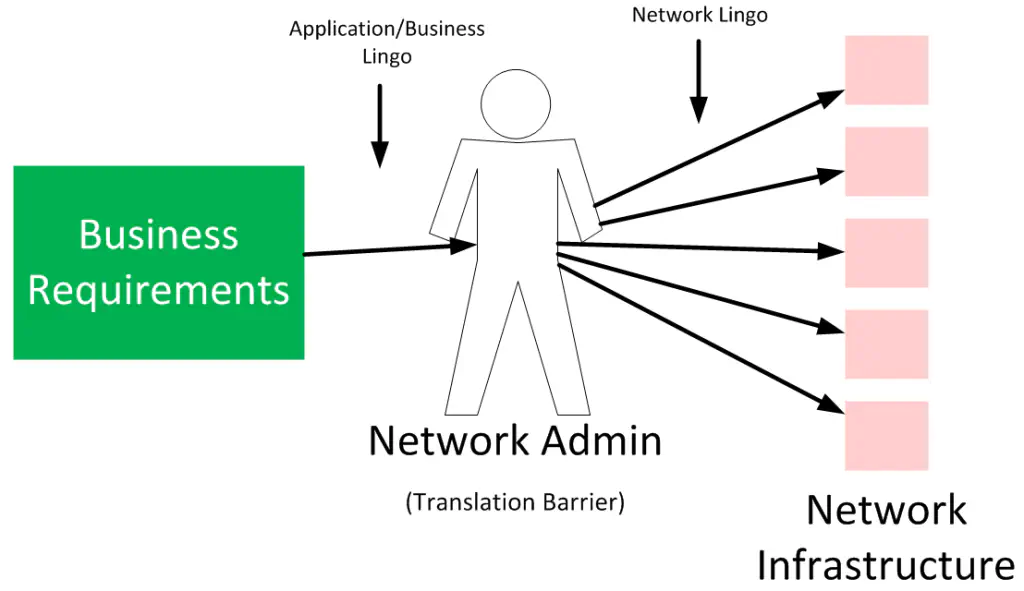

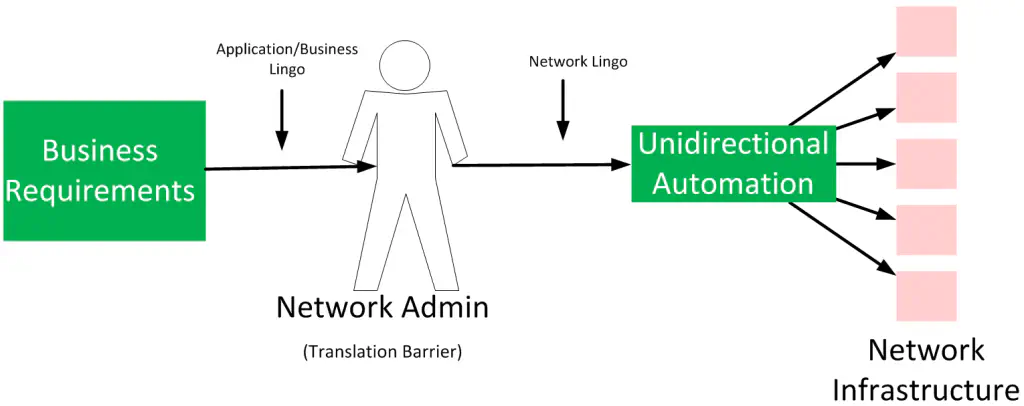

So I will use the term Unidirectional Automation to describe such an idea, and the fact that - though better than manual, from-scratch creation of configuration syntax - it won’t be enough for the systems of the next decade. It’s the idea of automating the process of imparting configuration knowledge into the network, from a human brain. The brain is necessary, because someone has to translate between business requirements and the manifestation of those requirements in specific network configuration syntax, right?

Some courageous folks have taken it upon themselves to write scripts that take configuration templates and automatically push them into network gear (pasting them over an SSH connection in most cases). Is this better than manually going through the network box-by-box to make changes? Yes - since inevitably the latter approach will result in inconsistency. However, this doesn’t do anything more than push input into the network as a system, directly from our brains. We still have to impart knowledge in a particular way whenever a change needs to be made.

Don’t get me wrong - this is a great step in the right direction. VMware’s introduction of the vCenter product showed us what’s possible if we treat our x86 servers as a pool of compute resources as opposed to a collection of boxes, and this approach does the same thing for the network. Just as VMware and other companies realized though, this centralization of policy application isn’t the end-goal. It is a solid foundation for the real intelligence to be built on top. This is why I made the case that network automation - even unidirectional - is in my mind a pre-requisite for the more advanced networking technologies you may be hearing about in the next few years as a result of the SDN hypestorm.

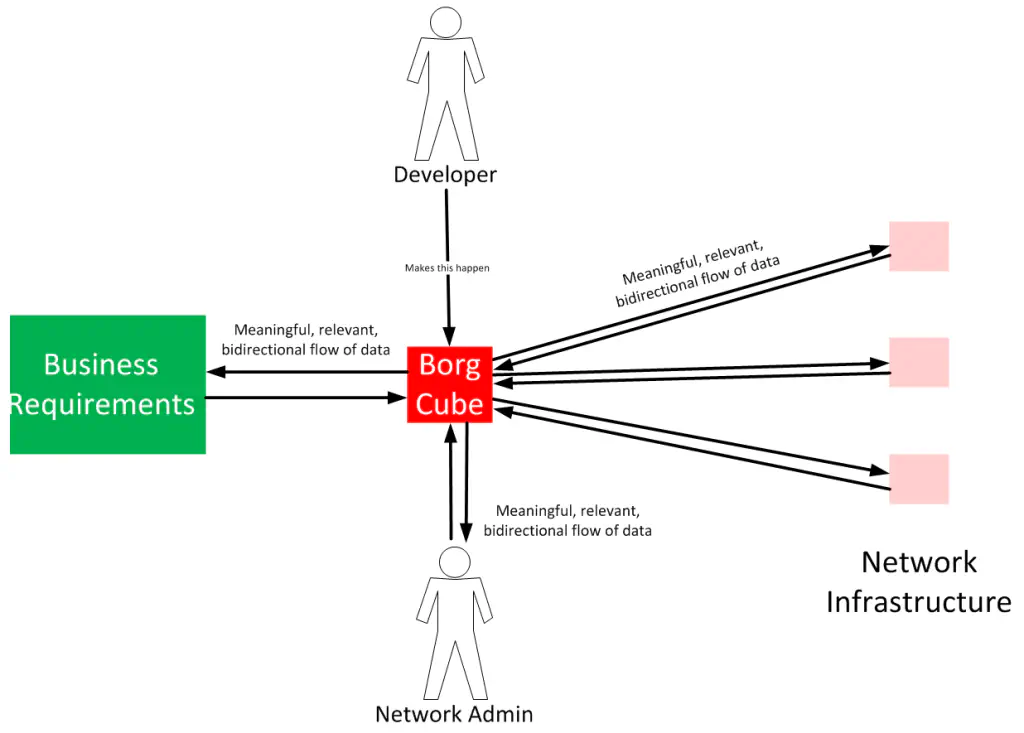

This model emphasizes the need for a human being to serve as the “translation barrier” between application and network lingo. So, I submit the following next-step to unidirectional automation. In order to remove the human being from this flow of information, something needs to take its place (unless you want your CEO logging into your network gear - up to you). We’ll call this “thing” the “Borg Cube” for lack of a better term. The Borg Cube can’t just be some self-enclosed box of artificial intelligence (yet), it still requires that we push some kind of initial intent into the system as the knowledgeable human beings that we are. It also might require a software developer to create said cube in the first place, and maintain it once in place.

What sets Borg Cube apart from unidirectional automation is that it sits in the middle of it all, constantly sending AND receiving information from the business, the network admin, and the infrastructure itself, supplying feedback to each system that it touches. It will also connect to other business and infrastructure systems, providing information that those systems can act upon.

It’s interesting to note that the most major change in this diagram compared to the other two is the removal of the human being from the direct flow of knowledge between the business and its infrastructure. I think this notion of relinquishing direct control is one of the biggest key points to moving networking forward, and it’s why I included a developer. We have a lot of work ahead of us to get to this point, but it’s what a lot of us are working really hard on right now.

If you’re doing unidirectional automation now, think about what it might take to start removing yourself from this path - believe me, you’ll be a fan of the results. If you’re not even there yet, consider what you spend most of your time doing, and consider what it would take to consolidate those tasks using a few popular tools that exist today.