[SDN Protocols] Part 4 - OpFlex and Declarative Networking

September 22, 2014 in Systems13 minutes

In this post, we will be discussing a relatively new protocol to the SDN scene - OpFlex. This protocol was largely championed by Cisco, but there are a few other vendors that have announced planned support for this protocol. I write this post because - like OVSDB - there tends to be a lot of confusion and false information about this protocol, so my goal in this post is to provide some illustrations that (hopefully) set the record straight, with respect to both OpFlex’s operation, and it’s intended role.

Before I get started, I would be remiss to not point you towards a brilliant article by Kyle Mestery titled “OpFlex is not an OpenFlow Killer”. At the time the article was written, Kyle was working for Noiro, a team within the INSBU at Cisco focused (at least primarily) on open source efforts in SDN, and the creators of OpFlex.

The Declarative Model of Network Programmability

Before we get into the weeds of the OpFlex protocol, it’s important to understand the model that OpFlex intends to address. OpFlex is the protocol du jour within a Cisco ACI based datacenter fabric, but broadly, OpFlex represents a declarative programmability model, and is being adopted by a few other vendors, as well as Open Source initiatives like OpenDaylight. But what is declarative programming?

In contrast, Cisco refers to the OVSDB protocol as “imperative”. In their view, if the OVSDB server schema contains table information about ports and bridges, then the client making OVSDB calls must also know about these constructs. Cisco likes to repeatedly refer to OVSDB as the “imperative” SDN protocol, but this is a bit of a misnomer in my opinion.

OVSDB methods function very similar to a database language like SQL, and as with SQL, we can be much less verbose with the data we want to manipulate within an OVSDB implementation. We can do things like:

“Whenever X is equal to 7, change Y to 9”

We don’t have to write loops and if statements to go through entire data structures, we simply describe what it is that we intend to do. So, SQL is a fairly good example of declarative programming.

I don’t speak for Cisco, but I believe their point is that - even in this case - you still have to know the schema being used (i.e. the existence of X and Y), which in the world of SDN, places constraints on the way we program the network. If I had to guess, I’d say this is more closely what Cisco means by “imperative”.

To this end, Cisco has been pitching their version of the declarative network programmability model, which essentially involves two main tenets:

- Create “buckets” that describe a type of application and it’s network-specific properties

- Create policies that describe how these buckets should communicate with each other

In this way, the model focuses on connectivity, and not specific device syntax. We’ll get into the specific benefits, but this essentially means that the API we use on the network (in this case OpFlex) doesn’t actually know how to spin up interfaces, or configure VLANs. That’s left to the end devices to figure out on their own. For the purposes of this article, whenever I refer to “declarative” or “declarative model” I’m describing what I see as Cisco’s view of this term, which is a protocol and schema-agnostic model of network programmability.

Group Policy

In my last section, I described the two tenets that Cisco uses to define their declarative model. Cisco ACI is based on these tenets, as is a project they’ve created within both OpenDaylight and OpenStack Neutron - called Group Policy.

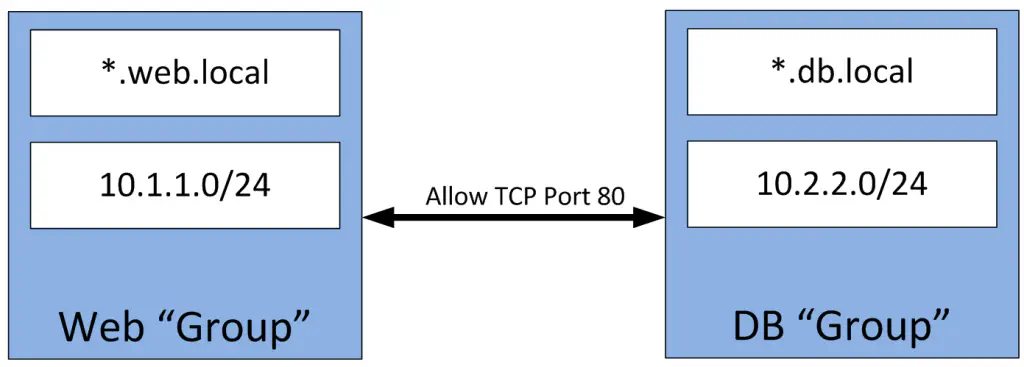

In this model, rather than worrying about the details of how two network endpoints find each other (VLANs, VXLAN, routing, etc.), an administrator will define “groups” by application attributes. These are typically identified by a network administrator when discussing the implementation of a new application anyways. Properties like DNS name or IP subnet are good examples of what could be used to define a portion of an application.

Once this is done, an administrator connects groups together with a “contract” that states what these groups are allowed to do with each other. This is similar to “old school” access control lists - statements like “allow communication on destination TCP port 80” would be a common contract statement.

The purpose of a model like this isn’t to hide the details from those that understand them (i.e. a network administrator) but instead from those that do not (i.e. application developers). They are able to re-use contracts and groups that a network administrator defines, and as a result, this model is geared more towards that portion of IT.

So if you’re a network administrator reading this and wondering if you’ll lose your ability to troubleshoot the details underneath, the goal of this model is not to hide that from you. It is essentially a new way of interacting with application teams that makes more sense to them.

The Translation Boundary

Now that we understand the model OpFlex is intended to fit into, let’s take a look at some visuals that will illustrate how OpFlex changes the paradigm of pushing policy to network elements. I mentioned that the Group Policy idea allows administrators to be more generic with describing network policy. The policies created here are stored in a Policy Repository, co-resident with the Group Policy implementation - likely a controller of some kind.

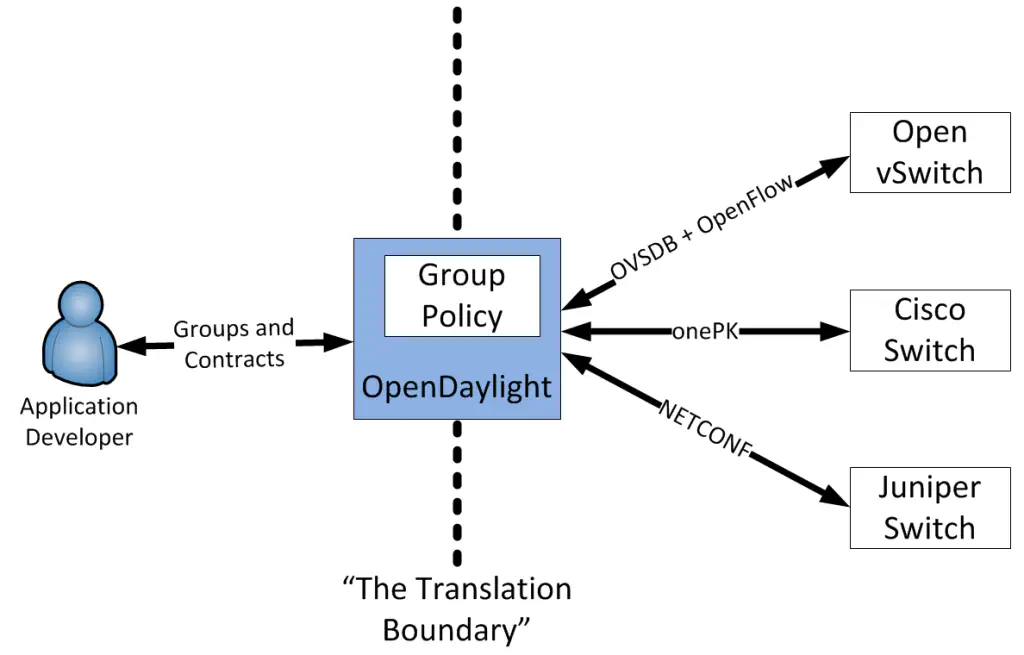

Let’s stop here and imagine what it would be like if we used a Group Policy model with a controller like OpenDaylight, and southbound protocols we’ve already looked at like OpenFlow and OVSDB. At the end of the day, some kind of specific implementation has to take place. These group policies are nice to define from an application perspective - it does make things simpler.

However we still need to get things like VXLAN and VLAN connectivity working. We have to figure out how to apply security rules. We have to configure routing. All of this needs to happen for the above group policy model to actually work. Something has to translate between the abstract and the particular.

For lack of a better term, I’m calling this the “translation boundary” - the place where the declarative model is interpreted into discrete actions.

When interacting with specific network elements - typically heterogenous - a controller like OpenDaylight will have to interpret calls made via the northbound API into specific network elements based off of what they’re known to support. As shown above, a Juniper switch may use NETCONF, a Cisco switch may leverage the onePK libraries, and Open vSwitch can use the ever-popular OVSDB+OpenFlow combo. The controller must keep track of which method each device supports, and leverage the appropriate protocol for each device.

Group Policy doesn’t inherently change this - as shown on the wiki, it really provides a new model on the northbound side - that is, between the applications/developers and the controller itself. The translation between the abstract “groups and contracts” model has to be translated to specific southbound protocols within the controller. At this point it’s pretty speculative, but you might imagine a few potential problems with this approach.

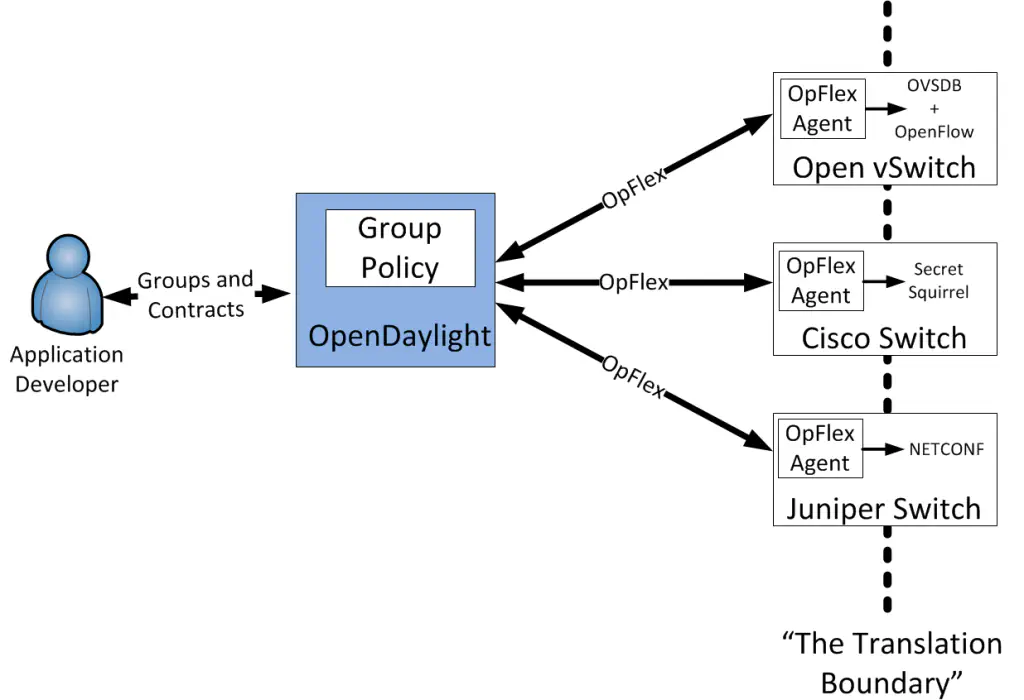

Rather than deal with the translation in this way, OpFlex fundamentally moves this translation boundary closer to the network devices themselves. OpFlex becomes the protocol that communicates generic policies and intentions to a local agent on each network device, and that agent is responsible for translating to specific protocols.

Again, this is all very new, but the arguments in favor of a model like this seem to be well-founded. Time will tell what kind of environments require this shift of the translation boundary, but on paper, this greatly simplifies the interaction with the network edge from both a scalability and complexity perspective. The controller doesn’t have to speak multiple protocols southbound - each endpoint is responsible for interpreting the controller’s original intent in a locally significant way. This is the fundamental basis of Promise Theory, which ACI is largely based on.

Each device uses the same OpFlex protocol, provided an agent exists for it, so there’s no need for the controller to keep track of anything from a device perspective. It’s job becomes simply to ensure it’s own policy repository and that of the network devices are in sync.

This also means the controller is even less important from a failure domain perspective. You won’t be able to create new policies if the controller is down, but current policies will continue to be enforced, and regular routing, switching, learning, etc. can proceed normally. In addition, this also allows two endpoints to share policy information with each other directly in the event the controller is down.

This “distributed controller” architecture is becoming increasingly common, as we’ve seen similar approaches from companies like Plexxi and Pluribus. We’ve moved out of the very academic “punt everything to the controller”, to the more realistic “the controller does all the work but is not in the forwarding path”, and now to “the controller is just there to ensure policy is distributed well”.

All of this said, whether the translation boundary is at the controller, or on the end devices, the northbound applications like OpenStack, CloudStack, etc. still don’t need to worry about implementation details, because the Group Policy concept defines that interaction. In my opinion, that’s where the real value is. The industry generally accepts that at some level, a less imperative model is necessary. The SAL within ODL is an example of this. We don’t want cloud orchestration systems to know how to speak to our switches….we’d rather handle that in a specialized controller like OpenDaylight, and allow OpenDaylight to translate between this abstract northbound language and the language the switches speak.

OpFlex as a System

You might have been asking why I spent two sections talking about something other than OpFlex. The reality is that once you understand all the information above, OpFlex is not that complicated. Taking a look at the OpFlex architecture page within the OpenDaylight wiki, we can see the elements that play a role in an OpFlex system, and how communication between them takes place.

That architecture page is EXTREMELY exhaustive, and despite the obvious “work in progress” labels, it is already a very good resource for understanding OpFlex. I won’t even try to duplicate details here - please head over to that architecture page and read up on the components of an OpFlex system.

Mike Dvorkin describes this aptly in <= 140 characters:

OpFLEX is a POLICY AGENT that renders and enforces polices locally using the best technology for the task. Including OVSDB and OpenFlow.

— dvorkin(dvorkin(..)) (@dvorkinista) April 2, 2014In general, OpFlex is the protocol Cisco has devised to allow network devices and controllers to synchronize their local policy databases. As Mike said, this also includes an open source agent to interpret OpFlex to locally significant policies. This is why the statements and articles positioning OpFlex as a “competitor” or “killer” of other protocols is quite incorrect. OpFlex doesn’t modify flows on a data plane layer like OpenFlow. It also doesn’t make configuration changes like OVSDB. However, the paradigm in which OpFlex plays a role does change how these protocols are used.

The protocol itself is defined in an IETF draft, and contains a few terms you may remember from my OVSDB article. Like OVSDB, OpFlex leverages JSON-RPC for communication, and defines the JSON-RPC methods that describe OpFlex operation.

The draft also contains a system overview, where artifacts like the Policy Element, Policy Repository, and Observer are defined, as they are in the OpenDaylight architectural wiki page.

If you look at these methods, you can see that they are built to read and change data in something called a Managed Object tree. This is not a new concept; such a structure has been used often, and for a long time, to describe data elements and their relationships. Microsoft Active Directory is probably one of the most well-known MO tree implementations in the IT world.

It’s not even the first time Cisco’s used this. Mike Dvorkin used the same concept in building UCS Manager. If you’ve ever messed with the UCS Python SDK (and let’s be real….who hasn’t) you are very familiar with this, as this is the main method of interacting with UCSM programmatically.

Please refer to the draft on how the managed object structure within an OpFlex system is handled, but here is a decent overview of the MO tree structure as it pertains to Cisco ACI:

Disclaimer: Cisco was a vendor sponsor at this event (Network Field Day 8) and as a result, paid for a portion of my travel expenses to get to this event. They were not promised any consideration from me, nor did they ask for any. As always, the words that I write are my own.

OpFlex as an Agent

There’s another piece to an OpFlex system that I haven’t really talked about much yet. The Policy Element (Agent) pictured above is a very important piece of the picture. It is here that the agnostic, declarative OpFlex protocol must get interpreted to specific actions, relevant to that node.

It is important to mention that the OpFlex project within OpenDaylight is creating this policy agent, and open sourcing it.

Let’s say this agent is installed on a linux host running KVM and Open vSwitch. Open vSwitch doesn’t talk OpFlex, so this Policy Agent will communicate OpFlex with a controller of some kind, and keep a local copy of the policy repository. Based on the locally significant factors, a renderer will be used to translate between OpFlex, and whatever is needed on that specific node. This is why in my diagram, the “translation boundary” is pushed to the edge.

In our example, the policy agent will use renderers to make changes to the local OVS database tables, as well as make flow modifications using OpenFlow.

This piece is still being actively worked on (I don’t believe it will even be officially part of the OpenDaylight Helium release) so check back here for updates. In addition, definitely check out Scott Mann’s slides on OpFlex - he presented on a lot of this at LinuxCon and was cool enough to answer a few of my questions about OpFlex and related efforts.

Conclusion

OpFlex is an important piece of all this, but ultimately not where the value is. The open source agent, the group policy projects - all of these efforts are what shows value in my eyes. There was a lot of press and attention around the OpFlex protocol being positioned as a “competitor” to other protocols…..to that, I say: “meh”. Ultimately, OpFlex is just the “sync” protocol that Cisco created for their distributed system.

I do believe that some kind of declarative approach is needed for networking. There is some sexiness to being able to describe pieces of your infrastructure, and just connect the dots. I will always want to be able to dive deeper - this kind of functionality is great for closing the gap between infrastructure and applications, but when things go wrong I like to be able to troubleshoot.

There is a lot of activity going on that is focused on this model, both within and outside of Cisco. I think the industry generally accepts that this kind of thing is needed. Time will tell how this model manifests itself - I think we’re still in the early stages for the most part.