[SDN Protocols] Part 5 - NETCONF

March 30, 2015 in Systems8 minutes

For those that followed my SDN Protocols series last summer, you might have noticed a missing entry: NETCONF. This protocol has actually existed for some time (the original now-outdated specification was published in 2006), but is appearing more often, especially in discussions pertaining to network automation. The current, updated specification - RFC6241 - covers a fairly large amount of material, so I will attempt to condense here.

NETCONF operates at the management layer of the network, and therefore plays a role similar to that of OVSDB. This is in contrast to protocols like OpenFlow which operate at the control plane.

A key difference between NETCONF and other management protocols (including SNMP) is that NETCONF is built around the idea of a transaction-based configuration model. The NETCONF specification provides for some optional device capabilities aimed at assisting operators with the lifecycle of configuring a network device, such as rolling back a configuration upon an error. Unfortunately, not all network devices support such capabilities, but the protocol was built to make it easier to discover what kind of capabilities a network device can support.

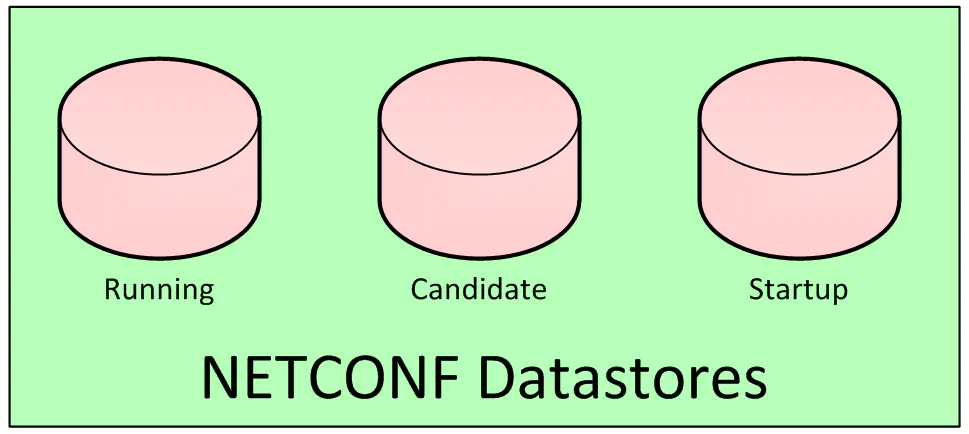

Configuration Datastores

Before getting into the semantics of the NETCONF protocol itself, it’s worth briefly jumping ahead to address the concept of a configuration datastore. For those experienced with Cisco networking gear, a good example of this would be the file “running-configuration”. When you run the command “copy running-config startup-config”, in essence, what you’re doing is overwriting one configuration datastore with another, even if that’s not quite what Cisco calls it.

Of course, NETCONF needs to be able to refer to such datastores in an agnostic way. To that end, there are three possible datastores that can be addressed by NETCONF: “running”, “candidate”, and “startup”.

You can think of the “candidate” datastore as a sort of “proposed” datastore, or a configuration that is staged, but not yet pushed to the forefront. Obviously, some network devices do not have a candidate datastore, because they don’t support this kind of configuration. If it does, then the server offers a device capability (more on these later) called “:candidate” that lets the client know that it can write to this datastore. This will require the client to also send a “commit” operation (made possible by the “:candidate” capability) in order to instruct the server to push the candidate datastore onto the running datastore - or in other words, cause the configuration to take effect on the network device.

If such a capability is not supported, then the NETCONF device must allow direct access to the “Running” datastore - otherwise, a client would have no way of making network changes take effect.

NETCONF RPC Transport

At it’s core, NETCONF functions on remote procedure calls, and uses an XML-based structure for both RPC requests, as well as replies. This allows both the client and the server to validate that a message adheres to the standard schema before it is sent, helping to reduce implementation errors.

In fact, the writers of the RFC have gone ahead and provided us with the schema in XSD format.

Any successful NETCONF message will be encapsulated within one of two RPC messages. First, the “rpc” tag is used for requests:

<rpc message-id="101"

xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:netconf:base:1.0"

xmlns:ex="http://example.net/content/1.0"

ex:user-id="fred">

<get/>

</rpc>

Next, a reply to a request uses an “rpc-reply” tag:

<rpc-reply message-id="101"

xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:netconf:base:1.0"

xmlns:ex="http://example.net/content/1.0"

ex:user-id="fred">

<data>

<!-- contents here... -->

</data>

</rpc-reply>

As you can see, the encapsulating transport for NETCONF is not incredibly interesting. If you remember the OVSDB post I wrote several months ago, you’ll recall that it uses a similar, relatively uninteresting transport (JSON-RPC). It is the operations inside that perform valuable tasks.

Operations

Just like any API built upon an RPC standard, NETCONF has several base operations that an operator can use. It can also provide a few others, as mentioned in the NETCONF specification, section 5:

NETCONF provides an initial set of operations and a number of

capabilities that can be used to extend the base. NETCONF peers

exchange device capabilities when the session is initiated[...]

First, let’s address these base operations.

| Operation Name | Description |

| get | Retrieve running configuration and device state information (great for "situational awareness") |

| get-config | Retrieve all or part of a specified configuration datastore. |

| edit-config | Loads all or part of a specified configuration to a target configuration datastore. |

| copy-config | Overwrites an existing configuration datastore with the contents of another. |

| delete-config | Deletes a configuration datastore (the "running" datastore cannot be deleted) |

| lock | Locks a configuration datastore so that changes are only allowed by the requesting client. |

| unlock | Releases a configuration datastore from a lock that was previously issued by the same client. |

| close-session | Attempts to gracefully terminate a NETCONF session (allows device to finish any tasks) |

| kill-session | Forces termination of a NETCONF session (device must stop all tasks and quit) |

Even these operations are fairly basic and self-explanatory. They provide for some basic mechanisms by which an operator (or controller) can work with a network device and its datastores.

Many operations, like any function you might write in Python or Golang, have mandatory and/or optional parameters that must be provided with the operation request. For instance, in order to edit a configuration, you must specify the datastore name when sending an “edit-config” operation. Some operations like “get” don’t have any arguments, and just return the running configuration and device state information when requested.

Capabilities

NETCONF, “capabilities” provide a way for a network device to offer functionality beyond the base operations listed in the previous section. Understandably, there is quite a variety of Network Operating Systems out there, and they can’t all have the same features. NETCONF allows endpoints to come to an agreement on which additional operations are suported.

For the purposes of illustration - here is a list of capabilities negotiated with a Juniper vSRX:

In [22]: conn.server_capabilities

Out[22]:

[

'http://xml.juniper.net/dmi/system/1.0',

'urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:netconf:capability:confirmed-commit:1.0',

'http://xml.juniper.net/netconf/junos/1.0',

'urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:netconf:capability:validate:1.0',

'urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:netconf:capability:candidate:1.0',

'urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:netconf:capability:url:1.0?protocol=http,ftp,file',

'urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:netconf:base:1.0'

]

I retrieved this list using a python library called ncclient - which is really the de facto open source library for working with NETCONF. More on this in a future post.

Upon the initialization of a new session, a NETCONF server will advertise to the client all of the capabilities it supports. This is called the “capability exchange”.

<hello xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:netconf:base:1.0">

<capabilities>

<capability>

urn:ietf:params:netconf:base:1.1

</capability>

<capability>

urn:ietf:params:netconf:capability:startup:1.0

</capability>

<capability>

http://example.net/router/2.3/myfeature

</capability>

</capabilities>

<session-id>4</session-id>

</hello>

In the above example from the NETCONF specification, the server is advertising the base NETCONF capabilities (the operations in the previous section), an additional optional capability, and lastly a custom capability that is described at the given URL. Through this, the client knows what it can and cannot do with this NETCONF server.

Many capabilities provide additional operations beyond the base operations described in the previous section. Capabilities can also modify the behavior of these operations (such as adding a certain operation parameter).

The NETCONF specification provides quite a few optional capabilities that a NETCONF server can support. I recommend you read the RFC for the details on these capabilities, but I will attempt to summarize here to whet your appetite:

| Capability Name | Description |

| Writable-Running | Indicates the NETCONF server allows clients to edit the running configuration directly |

| Candidate Configuration | Network device supports a candidate capability, as well as the "commit" operation |

| Confirmed Commit | Supports additional operations and parameters for the "commit" operation |

| Rollback-On-Error | Network device is able to roll-back to previous good configuration if changes fail |

| Validate | The device is able to check configuration for syntax errors before applying it to a datastore. |

| Distinct Startup | Device maintains a separate startup configuration that is loaded on boot. |

| URL | Device can also accept a URL as a parameter to operations like edit-config |

| XPath | The network device accepts XPath expressions within filters sent inside operations |

The NETCONF specification does allow operators or developers to create their own capabilities, and provides a template for these custom or proprietary capabilities in Appendix D. You may have noticed in my previous example that Juniper’s vSRX advertised two capabilities that they have created for their own implementation.

Miscellaneous

The NETCONF specification is lengthy. It would be difficult to cover the whole thing in a single blog post, or elegantly in multiple. To that end, I’d like to briefly mention two areas that are important to research on your own, but I left out:

The data that is contained within many NETCONF operations is not within the scope of the protocol itself. For the most part, NETCONF treats the data within the “config” element as opaque data, and makes the assumption that the endpoints are able to make sense of this data. (i.e. a configuration syntax for JunOS or IOS). However - it’s worth mentioning that YANG has a huge role to play in addressing this “gap”, and is a big reason why NETCONF and YANG are often joined at the hip when either come up in conversation.

NETCONF allows for filtering of elements within opaque configuration data, even with the aforementioned limitation on data modeling. The specification contains a very large section covering this topic.

Conclusion

I am encouraged at the role Netconf can play in bridging the gap between traditional “box-by-box” networking and network-wide programmability. When diving into NETCONF, I didn’t get the sense that it was created to push some kind of agenda, which unfortunately is true for numerous standard protocols. In NETCONF, I see a well-designed system for interacting with network devices.

Of course, it takes a lot more work over the top of such a protocol to create a proper network orchestration system, but the great thing about NETCONF is that it doesn’t force you into a rabbit hole in this respect.

I encourage you to explore the various resources I’ve referenced in this article - there’s only so much one blog post can cover. To that end, here are a few additional resources I did not mention: