Open Source Routing: Practical Lab

June 15, 2015 in Systems11 minutes

Earlier, I wrote about some interesting open source routing software that I’ve been exploring lately. In this post, I’ll provide you with some tools to get this lab running on your lab, using Vagrant and Ansible.

In this post, I’ll be using VirtualBox, and also Ansible and Vagrant. For this purpose, I’m assuming you’re at least somewhat familiar with these tools.

Please checkout my GitHub repository for access to the latest versions of all of the files we’ll discuss below - and an easy way to spin all of this up yourself.

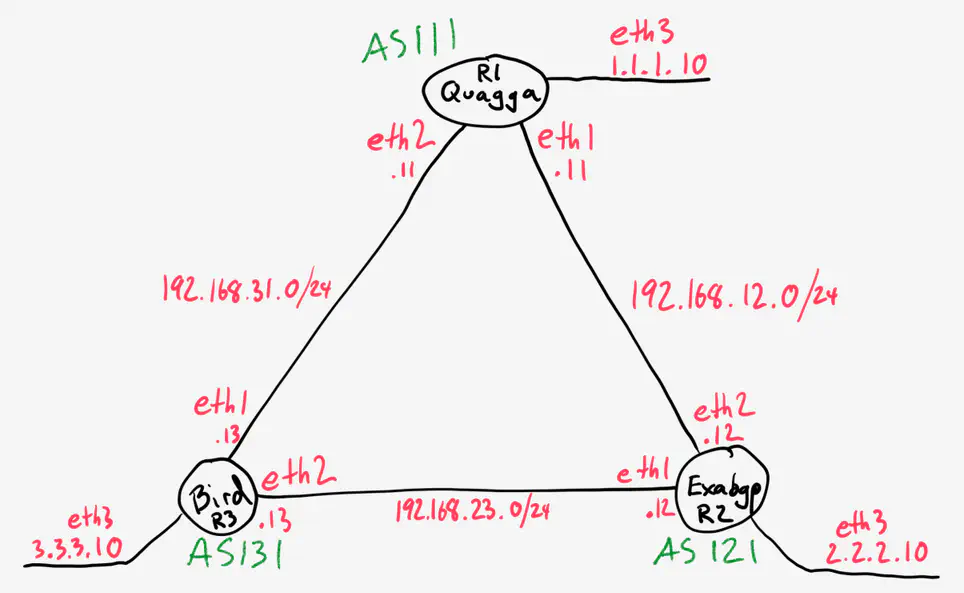

Topology

First, here’s the topology we’ll be working with.

All “circuits” are implemented using VirtualBox host networks, described in the Vagrantfile:

# -*- mode: ruby -*-

# vi: set ft=ruby :

VAGRANTFILE_API_VERSION = "2"

Vagrant.configure(VAGRANTFILE_API_VERSION) do |config|

config.vm.box = "trusty64"

config.vm.box_url = "http://cloud-images.ubuntu.com/vagrant/trusty/current/trusty-server-cloudimg-amd64-vagrant-disk1.box"

config.vm.define "r1" do |r1|

r1.vm.host_name = "r1"

r1.vm.network "private_network",

ip: "192.168.12.11",

virtualbox__intnet: "01-to-02"

r1.vm.network "private_network",

ip: "192.168.31.11",

virtualbox__intnet: "03-to-01"

r1.vm.network "private_network",

ip: "1.1.1.10",

virtualbox__intnet: "Network to Advertise"

r1.vm.provision "ansible" do |ansible|

ansible.playbook = "r1.yml"

end

end

config.vm.define "r2" do |r2|

r2.vm.host_name = "r2"

r2.vm.network "private_network",

ip: "192.168.23.12",

virtualbox__intnet: "02-to-03"

r2.vm.network "private_network",

ip: "192.168.12.12",

virtualbox__intnet: "01-to-02"

r2.vm.network "private_network",

ip: "2.2.2.10",

virtualbox__intnet: "Network to Advertise"

r2.vm.provision "ansible" do |ansible|

ansible.playbook = "r2.yml"

end

end

config.vm.define "r3" do |r3|

r3.vm.host_name = "r3"

r3.vm.network "private_network",

ip: "192.168.31.13",

virtualbox__intnet: "03-to-01"

r3.vm.network "private_network",

ip: "192.168.23.13",

virtualbox__intnet: "02-to-03"

r3.vm.network "private_network",

ip: "3.3.3.10",

virtualbox__intnet: "Network to Advertise"

r3.vm.provision "ansible" do |ansible|

ansible.playbook = "r3.yml"

end

end

end

Initial Setup

All configuration files and Ansible playbooks necessary for configuring all three virtual machines are provided in the GitHub repository. As you may have seen in the Vagrantfile listed above, all of these playbooks are linked to each virtual machine, so the steps required to clone this repo, and get the lab running are very simple:

~$ git clone https://github.com/Mierdin/ossrouting.git

~$ cd ossrouting

~$ vagrant up

In case you’re not familiar with Vagrant, the last step will create and start all virtual machines, as well as provision them using Ansible. If you wish to make changes to any of the files in this repo, you’ll have to run “vagrant provision” to push those changes into the VMs once they’ve been initially provisioned once.

At this point, you should have running VMs that have been configured to run BGP with each other using the software on each. I will now go into detail on how to play with each instance - in order to follow along, you should SSH into each VM using Vagrant. If I’m talking about R1 (Quagga) for instance, you’d type:

~$ vagrant ssh r1

The specific name wil be listed at the top of each section.

Quagga (r1)

After provisioning, this virtual machine is actively running zebra and bgpd:

vagrant@r1:~$ service quagga status

bgpd zebra

As mentioned in the previous article, Quagga comes with a handy tool called “vtysh” that unifies the configuration for all running daemons under one CLI context, making it feel very similar to something like Cisco IOS.

vagrant@r1:~$ sudo vtysh

Hello, this is Quagga (version 0.99.22.4).

Copyright 1996-2005 Kunihiro Ishiguro, et al.

r1#

You may have to press “q” immediately after running vtysh to get to the Quagga CLI

Again - with a certain familiarity, you can display the running configuration, and notice a basic BGP configuration:

r1# show run

Building configuration...

Current configuration:

!

[omitted]

!

router bgp 111

bgp router-id 1.1.1.1

bgp log-neighbor-changes

network 1.1.1.0/24

neighbor 192.168.12.12 remote-as 121

neighbor 192.168.12.12 next-hop-self

neighbor 192.168.12.12 soft-reconfiguration inbound

neighbor 192.168.31.13 remote-as 131

neighbor 192.168.31.13 next-hop-self

neighbor 192.168.31.13 soft-reconfiguration inbound

You can also show the active BGP neighbors, as well as learned prefixes:

r1# show ip bgp sum

BGP router identifier 1.1.1.1, local AS number 111

RIB entries 5, using 560 bytes of memory

Peers 2, using 9120 bytes of memory

Neighbor V AS MsgRcvd MsgSent TblVer InQ OutQ Up/Down State/PfxRcd

192.168.12.12 4 121 18 22 0 0 0 00:16:16 1

192.168.31.13 4 131 43 40 0 0 0 00:34:59 1

Total number of neighbors 2

r1# show ip bgp

BGP table version is 0, local router ID is 1.1.1.1

Status codes: s suppressed, d damped, h history, * valid, > best, i - internal,

r RIB-failure, S Stale, R Removed

Origin codes: i - IGP, e - EGP, ? - incomplete

Network Next Hop Metric LocPrf Weight Path

*> 1.1.1.0/24 0.0.0.0 0 32768 i

*> 2.2.2.0/24 192.168.12.12 0 121 i

*> 3.3.3.0/24 192.168.31.13 0 63000 63000 63000 131 i

Obviously, there are quite a few operational differences between Quagga and the “standard” network operating systems it mimics - if you want to make changes to Quagga configuration, your options are limited to either changing the configuration files behind the scenes and restarting the service(s), or making changes from vtysh. The former option is what I’m doing with Ansible, but this has obvious drawbacks in production.

If you exit out to the shell, you’ll notice that Quagga pushes these prefixes into the linux routing table proper:

vagrant@r1:~$ route

Kernel IP routing table

Destination Gateway Genmask Flags Metric Ref Use Iface

default 10.0.2.2 0.0.0.0 UG 0 0 0 eth0

1.1.1.0 * 255.255.255.0 U 0 0 0 eth3

2.2.2.0 192.168.12.12 255.255.255.0 UG 0 0 0 eth1

3.3.3.0 192.168.31.13 255.255.255.0 UG 0 0 0 eth2

10.0.2.0 * 255.255.255.0 U 0 0 0 eth0

192.168.12.0 * 255.255.255.0 U 0 0 0 eth1

192.168.31.0 * 255.255.255.0 U 0 0 0 eth2

ExaBGP (r2)

This virtual machine has not been configured to start ExaBGP for us automatically, so we’ll need to do that. First, a quick tour. Upon connecting to our ExaBGP instance via SSH, you’ll notice there are a few files in ~/exabgp:

vagrant@r2:~$ cd exabgp

vagrant@r2:~/exabgp$ ll

total 20

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 May 28 03:51 ./

drwxr-xr-x 6 vagrant vagrant 4096 May 24 21:43 ../

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 285 May 28 03:51 advroutes.py

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 289 May 24 08:32 conf.ini

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 639 May 25 07:06 exabgp.env

“conf.ini” is our configuration file. If you look at this, you’ll notice a very basic, two-neighbor configuration:

vagrant@r2:~/exabgp$ cat conf.ini

group BGProuters {

router-id 2.2.2.2;

neighbor 192.168.12.11 {

local-address 192.168.12.12;

local-as 121;

peer-as 111;

graceful-restart;

process announce-routes {

run /usr/bin/python /home/vagrant/exabgp/advroutes.py;

}

}

neighbor 192.168.23.13 {

local-address 192.168.23.12;

local-as 121;

peer-as 131;

graceful-restart;

process announce-routes {

run /usr/bin/python /home/vagrant/exabgp/advroutes.py;

}

}

}

You might notice that each neighbor runs a small python script that outputs ExaBGP advertisements to stdout:

1vagrant@r2:~/exabgp$ cat advroutes.py

2#!/usr/bin/env python

3

4import sys

5import time

6

7messages = [

8'announce route 1.1.1.0/24 next-hop self',

9'announce route 2.2.2.0/24 next-hop self',

10'announce route 3.3.3.0/24 next-hop self',

11]

12

13time.sleep(2)

14

15while messages:

16 message = messages.pop(0)

17 sys.stdout.write( message + '\n')

18 sys.stdout.flush()

19 time.sleep(1)

20

21while True:

22 time.sleep(1)There is also an environment file in this directory that I used to ensure you could recreate the environment with my settings. Let’s start ExaBGP using the environment and configuration files in this directory.

vagrant@r2:~/exabgp$ exabgp --env exabgp.env conf.ini

I won’t bother posting the full output here, but the resulting output is fairly self-explanatory. It may take a few extra seconds to connect to our “r3” instance, running BIRD, but it should eventually connect.

BIRD (r3)

Very similar to Quagga, BIRD should already be running with the correct settings upon connection:

vagrant@r3:~$ service bird status

bird start/running, process 4252

The Ansible role for configuring BIRD is fairly simple - I really only needed to overwrite the default configuration file and make sure the BIRD service is started (after installing it of course).

The configuration file is interesting - it seems to allow us to perform some native scripting-esque logic right there in the file:

vagrant@r3:~$ sudo cat /etc/bird/bird.conf

router id 33.33.33.33;

protocol kernel {

persist;

scan time 20;

export all;

import all;

}

protocol device {

scan time 10;

}

protocol static {

}

protocol direct {

interface "eth3";

}

filter out_loopback1 {

if (net = 3.3.3.0/24) then

{

bgp_community.empty;

bgp_path.prepend(63000);

bgp_path.prepend(63000);

bgp_path.prepend(63000);

accept;

}

else reject;

}

protocol bgp ToQuagga {

description "Quagga";

debug { states, events };

local as 131;

neighbor 192.168.31.11 as 111;

next hop self;

route limit 50000;

default bgp_local_pref 300;

import all;

export filter out_loopback1;

source address 192.168.31.13;

}

protocol bgp ToExaBGP {

description "ExaBGP";

debug { states, events };

local as 131;

neighbor 192.168.23.12 as 121;

next hop self;

route limit 50000;

default bgp_local_pref 300;

import all;

export filter out_loopback1;

source address 192.168.23.13;

}

I have my familiar two-neighbor configuration, but each refers to an export filter called “out_loopback” which executes a basic conditional statement. If true, I advertise the route (and perform some AS path prepending).

What really sets BIRD apart from the others in my mind is the detached client, “birdc”. As mentioned in the previous article, this comes with the BIRD server itself, but it could communicate with the BIRD server through network RPCs, meaning it could be used remotely.

To start it in this environment, just run “sudo birdc” and start poking around:

vagrant@r3:~$ sudo birdc

BIRD 1.5.0 ready.

bird> show status

BIRD 1.5.0

Router ID is 33.33.33.33

Current server time is 2015-06-15 02:07:07

Last reboot on 2015-06-14 16:29:38

Last reconfiguration on 2015-06-14 16:29:38

Daemon is up and running

As you can see, this does seem to dump us into a CLI context of some kind, but it doesn’t seem to mimic any other style of CLI:

bird> ?

add roa ... Add ROA record

configure ... Reload configuration

debug ... Control protocol debugging via BIRD logs

delete roa ... Delete ROA record

disable <protocol> | "<pattern>" | all Disable protocol

down Shut the daemon down

dump ... Dump debugging information

echo ... Control echoing of log messages

enable <protocol> | "<pattern>" | all Enable protocol

eval <expr> Evaluate an expression

exit Exit the client

flush roa [table <name>] Removes all dynamic ROA records

help Description of the help system

mrtdump ... Control protocol debugging via MRTdump files

quit Quit the client

reload <protocol> | "<pattern>" | all Reload protocol

restart <protocol> | "<pattern>" | all Restart protocol

restrict Restrict current CLI session to safe commands

show ... Show status information

I recommend you poke around these options yourself, there are quite a few useful tools here. However, I would like to briefly mention that there seems to be some interesting configuration safety tools included in the daemon that the client is able to leverage. For instance - checking the validity of a configuration file:

bird> configure ?

configure ["<file>"] [timeout [<sec>]] Reload configuration

configure check ["<file>"] Parse configuration and check its validity

configure confirm Confirm last configuration change - deactivate undo timeout

configure soft ["<file>"] [timeout [<sec>]] Reload configuration and ignore changes in filters

configure timeout [<sec>] Reload configuration with undo timeout

configure undo Undo last configuration change

bird> configure check "/etc/bird/bird.good"

Reading configuration from /etc/bird/bird.good

Configuration OK

bird> configure check "/etc/bird/bird.bad"

Reading configuration from /etc/bird/bird.bad

/etc/bird/bird.bad, line 33: syntax error

This would be hugely useful for automating changes to this configuration file, since we don’t have to actually use a configuration file in order to check it (just need to point to it).

Of course, this section would be incomplete without checking on our neighbors. We can plainly see that our two intended BGP neighbor relationships are configured and working well, and we can also see that we’ve learned the prefixes we wanted to see, with the right number of paths:

bird> show protocols all ToExaBGP

name proto table state since info

ToExaBGP BGP master up 02:01:10 Established

(omitted)

bird> show protocols all ToQuagga

name proto table state since info

ToQuagga BGP master up 16:30:23 Established

(omitted)

bird> show route all

1.1.1.0/24 via 192.168.31.11 on eth1 [ToQuagga 16:30:22] * (100) [AS111i]

Type: BGP unicast univ

BGP.origin: IGP

BGP.as_path: 111

BGP.next_hop: 192.168.31.11

BGP.med: 0

BGP.local_pref: 300

via 192.168.23.12 on eth2 [ToExaBGP 02:01:10] (100) [AS121i]

Type: BGP unicast univ

BGP.origin: IGP

BGP.as_path: 121

BGP.next_hop: 192.168.23.12

BGP.local_pref: 300

2.2.2.0/24 via 192.168.23.12 on eth2 [ToExaBGP 02:01:10] * (100) [AS121i]

Type: BGP unicast univ

BGP.origin: IGP

BGP.as_path: 121

BGP.next_hop: 192.168.23.12

BGP.local_pref: 300

via 192.168.31.11 on eth1 [ToQuagga 02:00:59] (100) [AS121i]

Type: BGP unicast univ

BGP.origin: IGP

BGP.as_path: 111 121

BGP.next_hop: 192.168.31.11

BGP.local_pref: 300

3.3.3.0/24 dev eth3 [direct1 16:29:37] * (240)

Type: device unicast univ

via 192.168.23.12 on eth2 [ToExaBGP 02:01:10] (100) [AS121i]

Type: BGP unicast univ

BGP.origin: IGP

BGP.as_path: 121

BGP.next_hop: 192.168.23.12

BGP.local_pref: 300

via 192.168.31.11 on eth1 [ToQuagga 02:00:59] (100) [AS121i]

Type: BGP unicast univ

BGP.origin: IGP

BGP.as_path: 111 121

BGP.next_hop: 192.168.31.11

BGP.local_pref: 300

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this lab that I set up to help get your feet wet with open source routing! There’s much more where this came from - please don’t stop here, take this as far as it will let you. There are a lot of options involved that I didn’t have space to explore.

Please check out the Github project for access to all of the files you’ll need to get started. If you are so inclined, and you feel that I am missing a crucial piece of this lab, or maybe I have a typo, feel free to submit a PR!