Using Vagrant with CumulusVX

August 13, 2015 in Systems7 minutes

Cumulus recently announced their CumulusVX platform, which is a virtualized instance of their operating system typically found on network switches. They’ve provided a few options to run this, and in this blog post, I’ll be exploring the use of Vagrant to set up a topology with Cumulus virtual devices.

Brief Review of Vagrant

In software development, there is a very crucial need to consistently and repeatably set up development and test environments. We’ve had the “but it worked on my laptop” problem for a while, and anything to simplify the environment set up and ensure that everyone is on the same page will help prevent it.

Vagrant is a tool aimed at doing exactly this. By providing a simple CLI interface on top of your favorite hypervisor (i.e. Virtualbox) you can distribute Vagrantfiles, which are essentially smally Ruby scripts, and they provide the logic needed to set up the environment the way you want it. In addition, it can call external automation tools like Ansible and Puppet to go one step further, and actually interact with the operating system itself to perform tasks like installing and configuring software.

What we get out of a tool like Vagrant is a consistent distribution model, in a format that is built to address this use case.

Vagrant for Network Exploration

I’ve written before about how awesome it is to be able to run networking labs and demos using this tool, and I’m glad Cumulus jumped on the bandwagon.

I also like the fact that vendors like Juniper and Cumulus have leveraged existing tools like Vagrant and Ansible rather than reinventing the wheel. Rather than forcing us to use their own tools, they provide the basic building block, and use Vagrant as a “demilitarized zone” where all network OSs can come to play.

It’s true that the network connectivity described in a vagrantfile isn’t as simple as something like GNS3 - where you can drag and drop connections between nodes with ease. It looks like this is an option with Cumulus, and there are numerous blog posts showing how to do this with other NOS'.

However, I think the Vagrantfile format is good enough - certainly for simple topologies. It’s editable by a text editor, and we get the added benefit of being able to directly call Ansible to finish off the configuration. Learning a bit of extra syntax is a small price to pay for that benefit, in my opinion.

Prerequisites

You should have the following software installed. I will provide the versions that I have installed on my machine for your reference:

- Vagrant (I am using 1.7.2)

- Some kind of Hypervisor (Virtualbox works great, I’m using 4.3.26)

- Ansible (I am using 1.9.0.1)

Getting Started

Check out Cumulus’ documentation on setting up CumuluxVX with Vagrant. There are very comprehensive “getting started” instructions there, but here’s a brief summary:

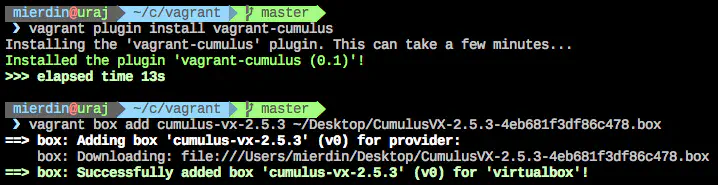

First, head over to the download page, and grab the .box file (listed as “Vagrant Box”). Follow the instructions to install this box, as well as install the vagrant plugin for Cumulus. Here’s a screenshot of me doing this on my laptop:

Once this is done, clone the CumulusVX Github repo, and navigate to the “demos” directory as shown below (I am using the HTTPS URL for simplicity):

$ git clone https://github.com/CumulusNetworks/cumulus-vx-vagrant.git

$ cd cumulus-vx-vagrant/vagrant/demos

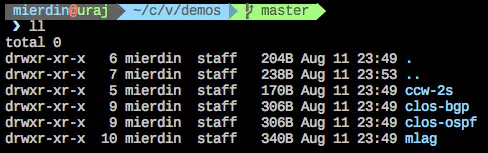

Here, you’ll notice a few subdirectories representing various topologies you can spin up:

Each contains a Vagrantfile (describes virtual machine properties, and network connectivity, among other things) and an Ansible playbook (.yml file)! The Vagrantfile references Ansible as a provisioner, and calls this .yml file to instruct Ansible the steps to take within the virtual machine once it’s stood up.

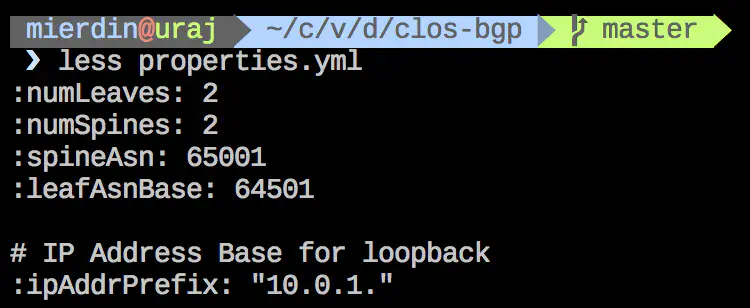

For this post, let’s look at clos-bgp. If you want, you can look at the contents of this Vagrantfile, but the folks from Cumulus wrote this in a way that leverages an outside file for determining certain operational parameters of the build - such as how many spine switches to have, or leaf switches, or what ASN they should have. That file is properties.yml:

You can modify these properties, and the Vagrantfile will take care of building out the lab according to those properties. So if you feel like you want to add another switch, do it in this properties file.

By the way, many of these parameters are passed through to our ansible playbook (in this case, “clbgp.yml”) so if you see these properties referenced in the playbook, that’s where they come from.

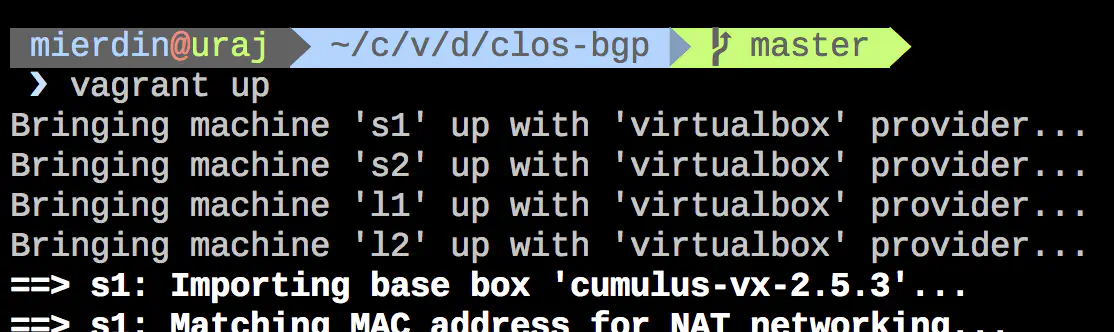

You only need to run “vagrant up” to make this lab come to life!

This will take a bit of time, but if you pay attention, you’ll see Vagrant initializing four virtual machines (two spines, and two leaves) as well as calling Ansible for each to perform provisioning tasks on each, such as setting up Quagga and enabling BGP on certain interfaces.

If all goes well, this process is entirely self-contained, and after simply running “vagrant up”, we get a fully functioning BGP lab per the specs in our properties file. Check it out!

~$ vagrant ssh s1

Linux cumulus 3.2.65-1+deb7u2+cl2.5+2 #3.2.65-1+deb7u2+cl2.5+2 SMP Wed Jul 29 14:21:03 PDT 2015 x86_64

Welcome to Cumulus VX (TM)

Cumulus VX (TM) is an open-source LINUX (R) distribution. License files are included with every package installed in the system and can be viewed in the /usr/share/*/doc/copyright files.

The registered trademark Linux (R) is used pursuant to a sub-license from LMI, the exclusive licensee of Linus Torvalds, owner of the mark on a world-wide basis.

Last login: Thu Aug 13 05:47:25 2015 from 10.0.2.2

vagrant@s1:~$ sudo vtysh

Hello, this is Quagga (version 0.99.23.1).

Copyright 1996-2005 Kunihiro Ishiguro, et al.

s1# show ip bgp

BGP table version is 3, local router ID is 10.0.1.1

Status codes: s suppressed, d damped, h history, * valid, > best, = multipath,

i internal, r RIB-failure, S Stale, R Removed

Origin codes: i - IGP, e - EGP, ? - incomplete

Network Next Hop Metric LocPrf Weight Path

*> 10.0.1.1/32 0.0.0.0 0 32768 i

*> 10.0.1.3/32 swp1 0 0 64502 i

*> 10.0.1.4/32 swp2 0 0 64503 i

Total number of prefixes 3

s1# show ip bgp sum

BGP router identifier 10.0.1.1, local AS number 65001

BGP table version 3

RIB entries 5, using 600 bytes of memory

Peers 2, using 33 KiB of memory

Neighbor V AS MsgRcvd MsgSent TblVer InQ OutQ Up/Down State/PfxRcd

swp2 4 64503 8 8 0 0 0 00:01:10 1

swp1 4 64502 8 8 0 0 0 00:01:50 1

Total number of neighbors 2

Video

I have created a short video outlining all these steps, so you can see it all in action. I didn’t want to go through the Ansible and Vagrantfile in too much depth in this post - since the goal was to just get you started quickly, but if you’d like a brief tour of these files, check it out:

Conclusion

Cumulus is on the right track here. I’ve written before about how easy of a decision it was for me to start using JunOS for all of my demos since they made a Vagrant box available, and Cumulus is now on that very short list of vendors.

I would like to see Cumulus move the CumulusVX image into a public repository like Hashicorp Atlas, just to cut out that extra step of importing the .box file. This would also help them avoid the uncomfortable situation that arises when someone else publishes it for them (like what happened to Fedora). Ultimately, the value of a tool like Vagrant is to accurately reproduce a test/dev environment, and the location of the .box file is just a part of that configuration, so why leave this up to the user? I’d much rather have vagrant download this from the source listed in the vagrantfile, and I would know that anyone else that used my vagrantfile is running the same image.

Still though, this is definitely a step in the right direction, and I would like to see more vendors doing this. There’s no reason to keep putting up barriers and EULAs between existing or prospective customers and the product you’re trying to get in their hands.