Network Namespaces: The New Access Layer

October 27, 2015 in Systems4 minutes

When considering containers and how they connect to the physical network, it may be easy to assume that this paradigm is identical to the connectivity model of virtual machines. However, the advent of container technology has really started to popularize some concepts and new terminology that you may not be familiar with, especially if you’re new to the way linux handles network resources.

What is a Namespace?

It’s important to understand this concept, because containers are NOT simply “miniature virtual machines”, and understanding namespaces is very important to conceptualizing the way a host will allocate various system resources for container workloads.

Generally, namespaces are a mechanism by which a Linux system can isolate and provide abstractions for system resources. These could be filesystem, process, or network resources, just to name a few.

The man page on linux namespaces goes into quite a bit of detail on the various types of namespaces. For instance, mount namespaces provide a mechanism to isolate the view that different processes have of the filesystem hierarchy. Process namespaces allow for process-level isolation, meaning that two processes in separate process namespaces can have the same PID. Network namespaces - the focus of this particular post - allow for isolation of network resources like interfaces or routing contexts.

Network namespaces will be illustrated in a little more detail later in the post, but for a really great introduction dedicated to the topic, head over to Scott Lowe’s post on the subject.

In order to fully appreciate the move to adopting network namespaces within a container networking context, it’s useful to see the history of how we got here, and how the access layer of our data center network has moved further and further into the server.

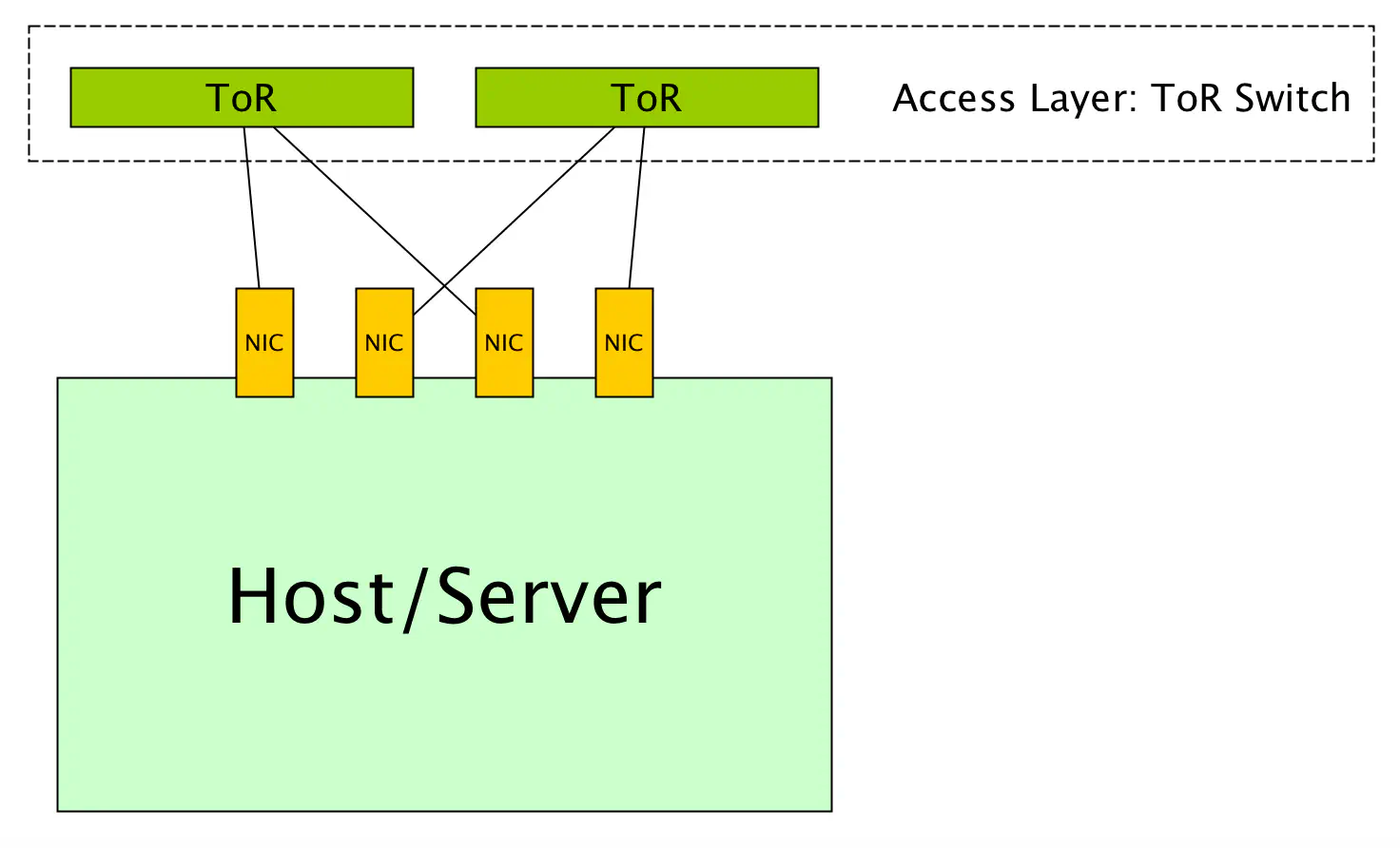

1 - The Physical Layer

Ah, the good old days. The days where you could touch and feel your access layer. You could point to it and show off “the place where those servers plug in”.

This was the “norm” for quite some time, because we were operating in a purely physical model. There was no server/network demarcation that manifested itself virtually.

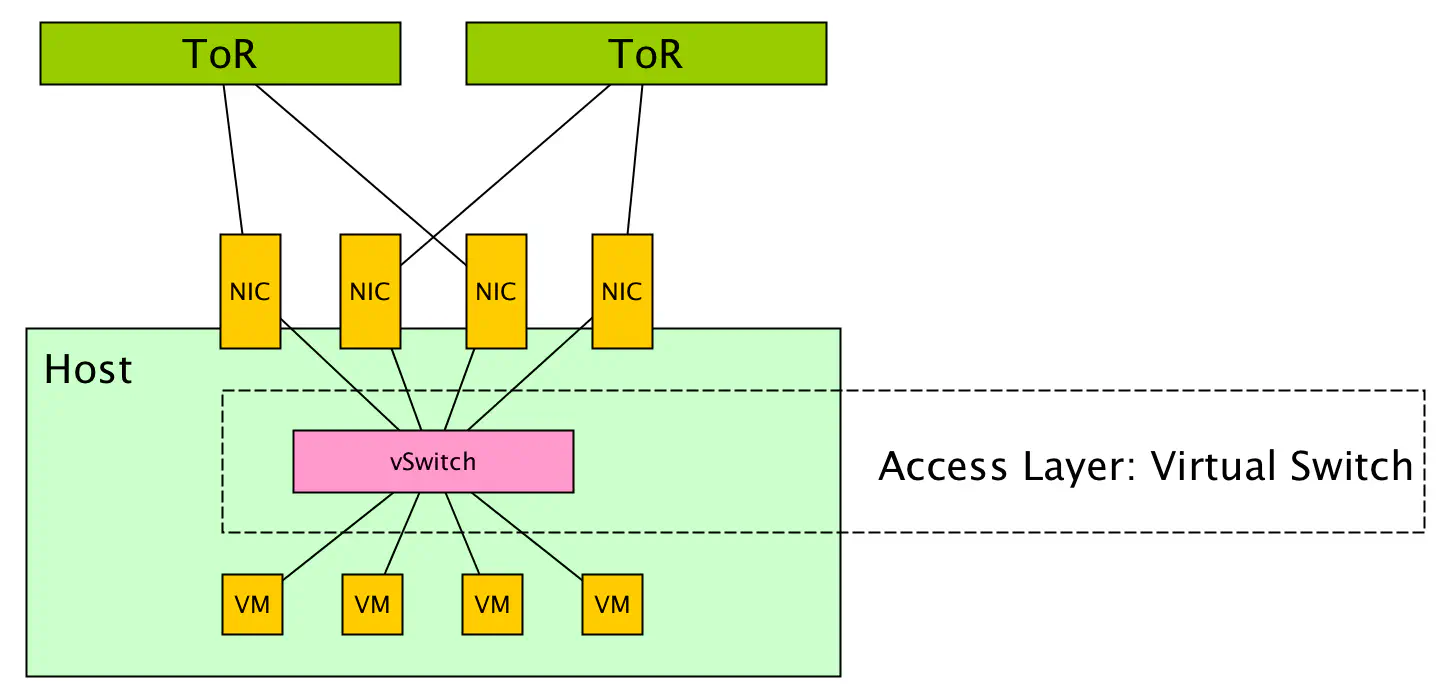

2 - The Virtual Layer

Of course, server virtualization changed the entire model. Virtual machines now plug into virtual ports provisioned onto a vSwitch, which is an entity that provides network functions similar to a physical switch, but purely in software.

We’ve learned a lot in the last decade about operating virtual network topologies at scale, and there are a lot of useful software projects - most notably Open vSwitch - that provide some very interesting functionality here, rather than waiting for physical switch vendors to make features.

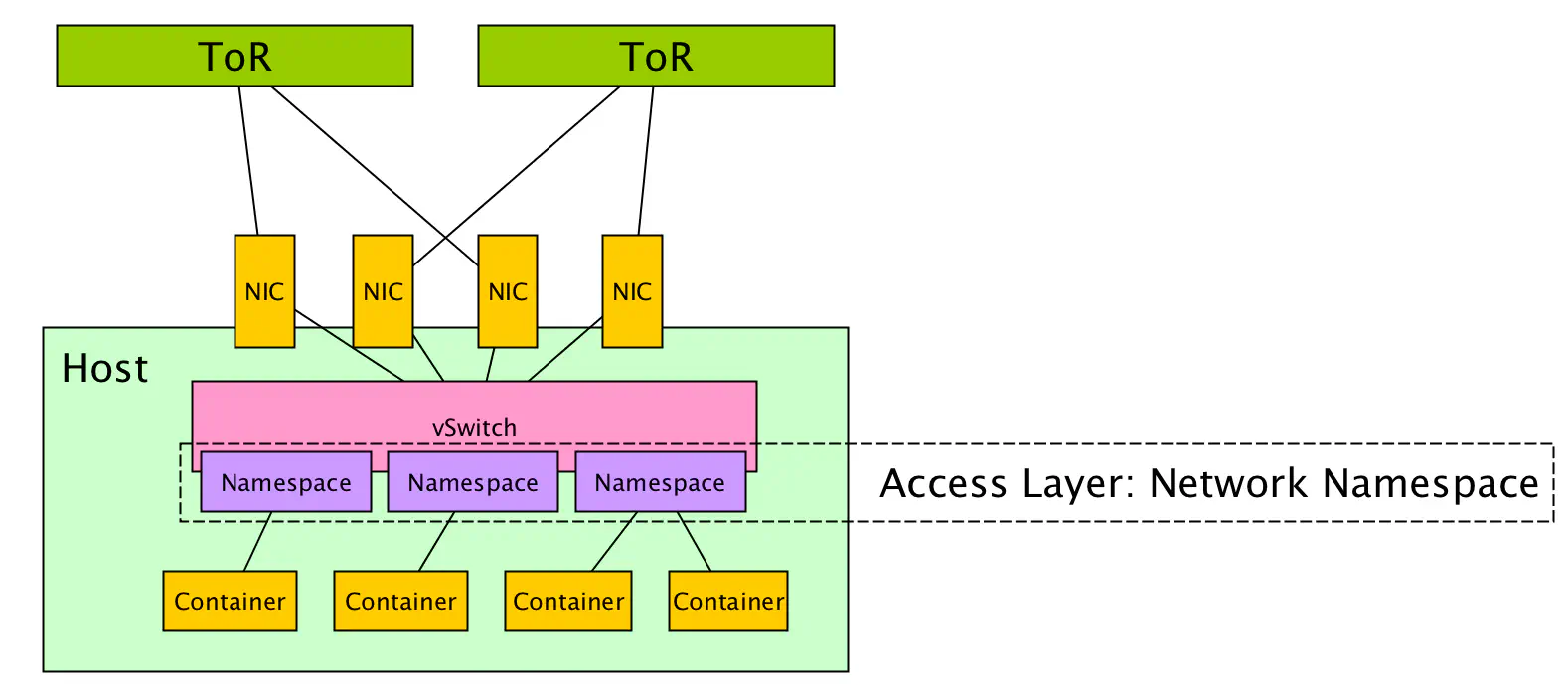

3 - The Namespace Layer

However, containers are not virtual machines. They’re not even “mini” virtual machines. Containers offer virtualization at a different level. Where server virtualization was fundamentally hardware virtualization, containers offer a virtualization of the operating system itself. One of the ways this is achieved is to leverage namespaces.

Now - a network namespace is not a new type of vSwitch. Leveraging network namespaces is not as drastic of a transition as was the move from physical to virtual switching. VMs and containers alike still plug into a vSwitch, but network namespaces provide us with a mechanism to isolate virtual network interfaces and provide some network context for workloads that are similar (i.e. belong to the same tenant).

In this way, we can run containers and offer network resources to them in a way that treats it like it’s the only process running on a box. Each container can run on an interface called “eth0”, they could each have their own routing table and source IP address, etc. This is what operating system virtualization brings us.

I won’t talk about it at length here in this network-centric post, but mount/filesystem namespaces are really interesting to me, especially within the context of persistent container data. The idea of leveraging these to give a container it’s own root filesystem is really interesting.

In short, the network namespace is the new access layer. No, it’s not changing the vSwitch paradigm, but rather adding on to it. In a multi-namespace scenario, the control plane software that programs the vSwitch would need to be network namespace aware, so that all namespaces could be administered effectively.

Real-World Examples

Docker has several documents outlining how it uses network namespaces to provide network resources to containers.

Kubernetes takes a different approach and creates a single network namespace for all containers that run in a pod. Containers within a pod can typically reach each other very easily on any port because they are on a shared network resource.