Principles of Automation

October 18, 2016 in Systems19 minutes

Automation is an increasingly interesting topic in pretty much every technology discipline these days. There’s lots of talk about tooling, practices, skill set evolution, and more - but little conversation about fundamentals. What little is published by those actually practicing automation, usually takes the form of source code or technical whitepapers. While these are obviously valuable, they don’t usually cover some of the fundamental basics that could prove useful to the reader who wishes to perform similar things in their own organization, but may have different technical requirements.

I write this post to cover what I’m calling the “Principles of Automation”. I have pondered this topic for a while and I believe I have three principles that cover just about any form of automation you may consider. These principles have nothing to do with technology disciplines, tools, or programming languages - they are fundamental principles that you can adopt regardless of the implementation.

I hope you enjoy.

It’s a bit of a long post, so TL;DR - automation isn’t magic. It isn’t only for the “elite”. Follow these guidelines and you can realize the same value regardless of your scale.

Factorio

Lately I’ve been obsessed with a game called “Factorio”. In it, you play an engineer that’s crash-landed on a planet with little more than the clothes on your back, and some tools for gathering raw materials like iron or copper ore, coal, wood, etc. Your objective is to use these materials, and your systems know-how to construct more and more complicated systems that eventually construct a rocket ship to blast off from the planet.

Even the very first stages of this game end up being more complicated than they initially appear. Among your initial inventory is a drill that you can use to mine coal, a useful ingredient for anything that needs to burn fuel - but the drill itself actually requires that same fuel. So, the first thing you need to do is mine some coal by hand, to get the drill started.

We can also use some of the raw materials to manually kick-start some automation. With a second drill, we can start mining for raw iron ore. In order to do that we need to build a “burner inserter”, which moves the coal that the first drill gathered into the second drill:

Even this very early automation requires manual intervention, as it all requires coal to burn, and not everything has coal automatically delivered to it (yet).

Now, there are things you can do to improve your own efficiency, such as building/using better tools:

However, this is just one optimization out of a multitude. Our objectives will never be met if we only think about optimizing the manual process; we need to adopt a “big picture” systems mindset.

Eventually we have a reasonably good system in place for mining raw materials; we now need to move to the next level in the technology tree, and start smelting our raw iron ore into iron plates. As with other parts of our system, at first we start by manually placing raw iron ore and coal into a furnace. However, we soon realize that we can be much more efficient if we allow some burner inserters to take care of this for us:

With a little extra work we can automate coal delivery to this furnace as well:

There’s too much to Factorio to provide screenshots of every step - the number of technology layers you must go through in order to unlock fairly basic technology like solar power is astounding; not to mention being able to launch a fully functional rocket.

As you continue to automate processes, you continue to unlock higher and higher capabilities and technology; they all build on each other. Along the way you run into all kinds of issues. These issues could arise in trying to create new technology, or you could uncover a bottleneck that didn’t reveal itself until the system scaled to a certain point.

For instance, in the last few screenshots we started smelting some iron plates to use for things like pipes or circuit boards. Eventually, the demand for this very basic resource will outgrow the supply - so as you build production facilities, you have to consider how well they’ll scale as the demand increases. Here’s an example of an iron smelting “facility” that’s built to scale horizontally:

Scaling out one part of this system isn’t all you need to be aware of, however. The full end-to-end supply chain matters too.

As an example, a “green” science pack is one resource that’s used to perform research that unlocks technologies in Factorio. If you are running short on these, you may immediately think “Well, hey, I need to add more factories that produce green science packs!”. However, the bottleneck might not be the number of factories producing green science, but further back in the system.

Green science packs are made by combining a single inserter with a single transport belt panel - and in the screenshot above, while we have plenty of transport belt panels, we aren’t getting any inserters! This means we now have to analyze the part of our system that produces that part - which also might be suffering a shortage in it’s supply chain. Sometimes such shortages can be traced all the way down to the lowest level - running out of raw ore.

In summary, Factorio is a really cool game that you should definitely check out - but if you work around systems as part of your day job, I encourage you to pay close attention to the following sections, as I’d like to recap some of the systems design principles that I’ve illustrated above. I really do believe there are some valuable lessons to be learned here.

I refer to these as the Principles of Automation, and they are:

- The Rule of Algorithmic Thinking

- The Rule of Bottlenecks

- The Rule of Autonomy

The Rule of Algorithmic Thinking

Repeat after me: “Everything is a system”.

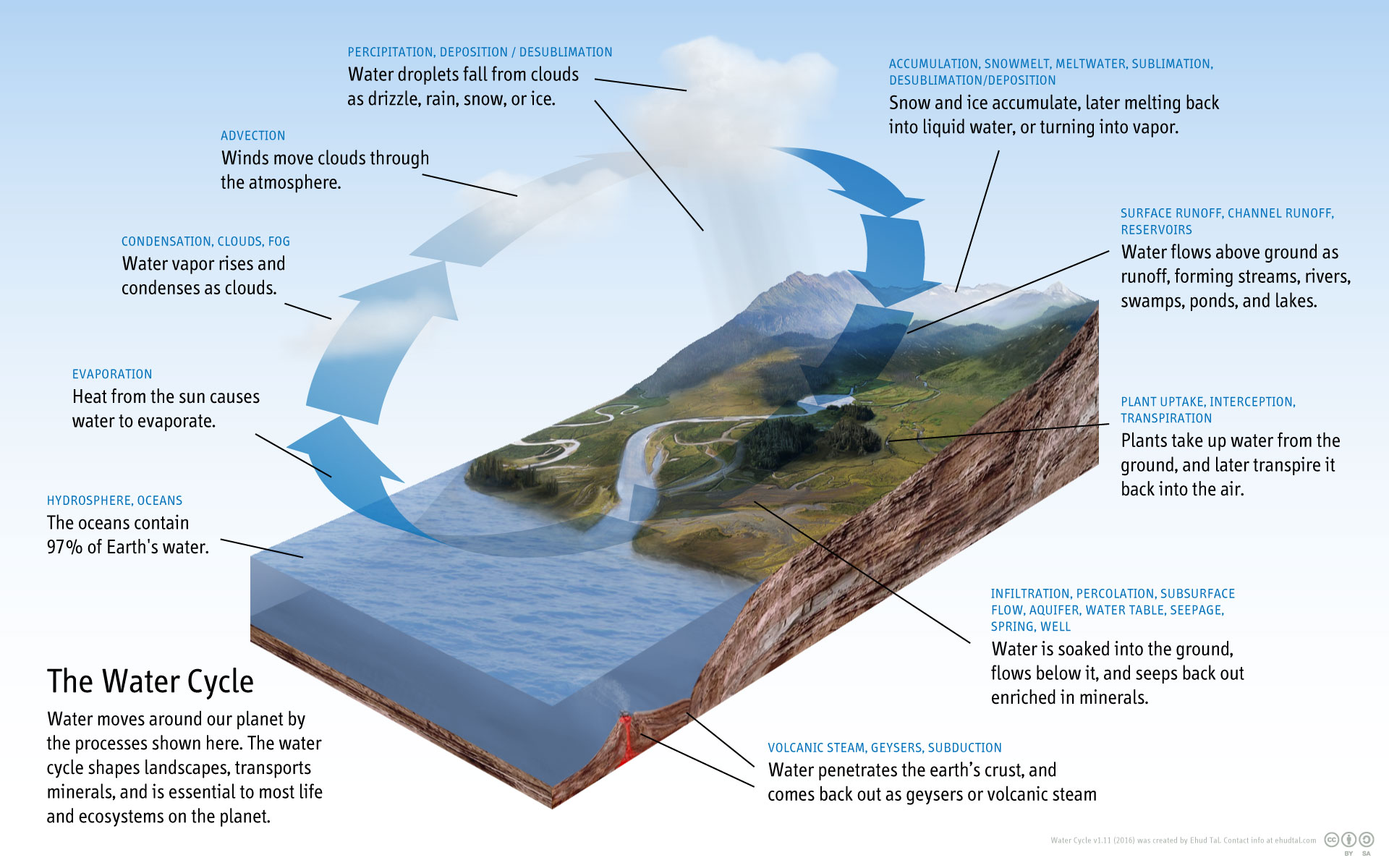

Come to grips with this, because this is where automation ceases to be some magical concept only for the huge hyperscale companies like Facebook and Google. Everything you do, say, or smell is part of a system, whether you think it is or not; from the complicated systems that power your favorite social media site, all the way down to the water cycle:

By the way, just as humans are a part of the water cycle, humans are and always will be part of an automated system you construct.

In all areas of IT there is a lot of hand-waving; engineers claim to know a technology, but when things go wrong, and it’s necessary to go deeper, they don’t really know it that well. Another name for this could be “user manual” engineering - they know how it should work when things go well, but don’t actually know what makes it tick, which is useful when things start to break.

There are many tangible skills that you can acquire that an automation or software team will find attractive, such as language experience, and automated testing. It’s important to know how to write idiomatic code. It’s important to understand what real quality looks like in software systems. However, these things are fairly easy to learn with a little bit of experience. What’s more difficult is understanding what it means to write a meaningful test, and not just check the box when a line of code is “covered”. That kind of skill set requires more experience, and a lot of passion (you have to want to write good tests).

Harder still is the ability to look at a system with a “big picture” perspective, while also being able to drill in to a specific part and optimize it…and most importantly, the wisdom to know when to do the latter. I like to refer to this skill as “Algorithmic Thinking”. Engineers with this skill are able to mentally deconstruct a system into it’s component parts without getting tunnel vision on any one of them - maintaining that systems perspective.

If you think Algorithms are some super-advanced topic that’s way over your head, they’re not. See one of my earlier posts for a demystification of this subject.

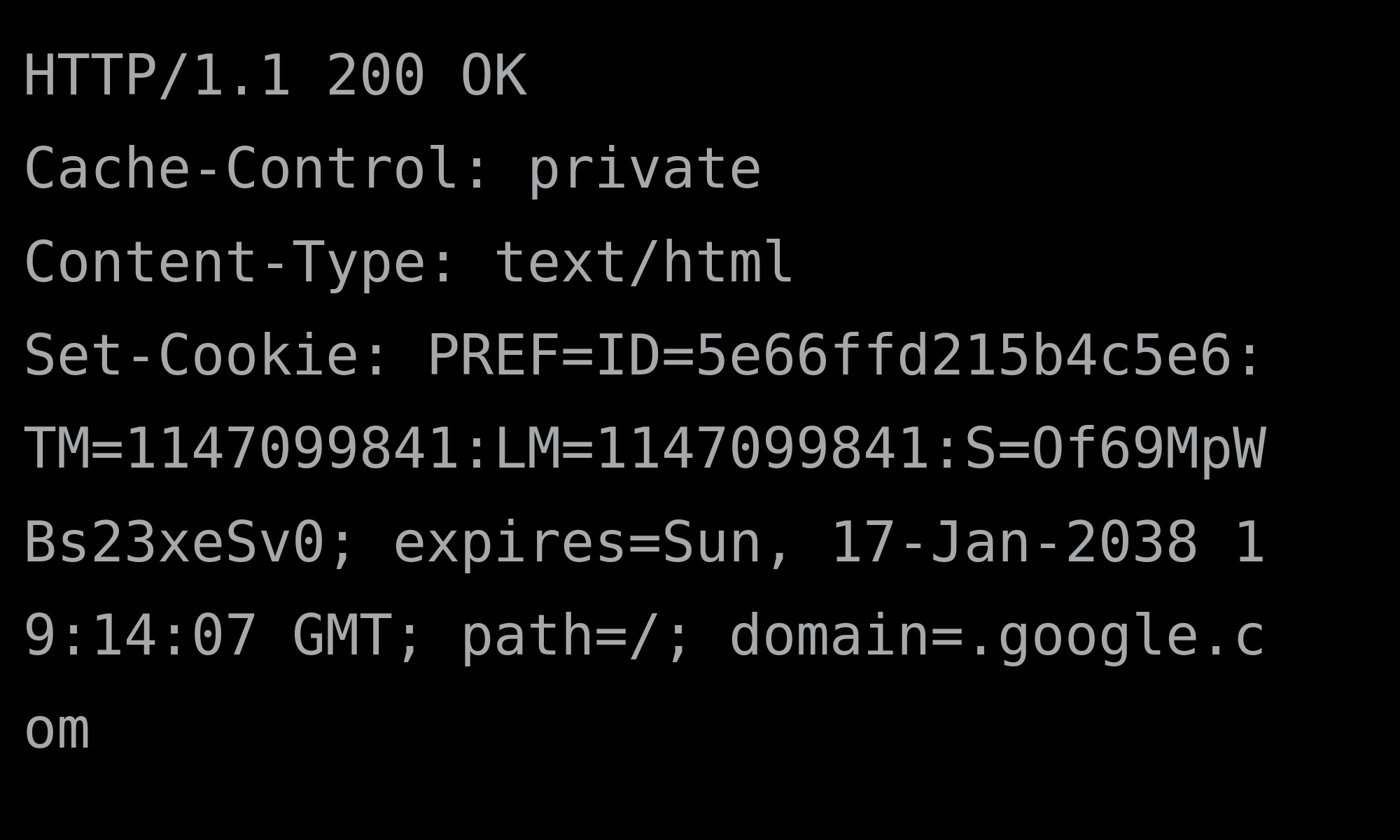

A great way to understand this skill is to imagine you’re in an interview, and the interviewer asks you to enumerate all of the steps needed to load a web page. Simple, right? It sure seems like it at first, but what’s really happening is that the interviewer is trying to understand how well you know (or want to know) all of the complex activities that take place in order to load a web page. Sure, the user types a URL into the address bar and hits enter - then the HTTP request magically takes place. Right? Well, how did the machine know what IP address was being represented by that domain name? That leads you to the DNS configuration. How did the machine know how to reach the DNS server address? That leads you to the routing table, which likely indicates the default gateway is used to reach the DNS server. How does the machine get the DNS traffic to the default gateway? In that case, ARP is used to identify the right MAC address to use as the destination for that first hop.

Those are just some of the high-level steps that take place before the request can even be sent. Algorithmic thinking recognizes that each part of a system, no matter how simple, has numerous subsystems that all perform their own tasks. It is the ability to understand that nothing is magic - only layers of abstraction. These days, this is understandably a tall order. As technology gets more and more advanced, so do the abstractions. It may seem impossible to be able to operate at both sides of the spectrum.

It’s true, no one can know everything. However, a skilled engineer will have the wisdom to dive behind the abstraction when appropriate. After all, the aforementioned “problem” seemed simple, but there are a multitude of things going on behind the scenes - any one of which could have prevented that page from loading. Being able to think algorithmically doesn’t mean you know everything, but it does mean that when a problem arises, it might be time to jump a little further down the rabbit hole.

Gaining experience with automation is all about demystification. Automation is not magic, and it’s not reserved only for Facebook and Google. It is the recognition that we are all part of a system, and if we don’t want to get paged at 3AM anymore, we may as well put software in place that allows us to remove ourselves from that part of the system. If we have the right mindset, we’ll know where to apply those kinds of solutions.

Most of us have close friends or family members that are completely non-technical. You know, the type that breaks computers just by looking at them. My suggestion to you is this: if you really want to learn a technology, figure out how to explain it to them. Until you can do that, you don’t really know it that well.

The Rule of Bottlenecks

Recently I was having a conversation with a web developer about automated testing. They made the argument that they wanted to use automated testing, but couldn’t because each web application they deployed for customers were snowflake custom builds, and it was not feasible to do anything but manual testing (click this, type this). Upon further inspection, I discovered that the majority of their customer requirements were nearly identical. In this case, the real bottleneck wasn’t just that they weren’t doing automated testing; they weren’t even setting themselves up to be able to do it in the first place. In terms of systems design, the problem is much closer to the source - I don’t mean “source code”, but that the problem lies further up the chain of events that could lead to being able to do automated testing.

I hear the same old story in networking. “Our network can’t be automated or tested, we’re too unique. We have a special snowflake network”. This highlights an often overlooked part of network automation, and that is that the network design has to be solid. Network automation isn’t just about code - it’s about simple design too; the network has to be designed with automation in mind.

This is what DevOps is really about. Not automation or tooling, but communication. The ability to share feedback about design-related issues with the other parts of the technology discipline. Yes, this means you need to seek out and proactively talk to your developers. Developers, this means sitting down with your peers on the infrastructure side. Get over it and learn from each other.

Once you’ve learned to think Algorithmically, you start to look at your infrastructure like a graph - a series of nodes and edges. The nodes would be your servers, your switches, your access points, your operating systems. These nodes communicate with each other on a huge mesh of edges. When failures happen, they often cause a cascading effect, not unlike the cascading shortages I illustrated in Factorio where a shortage of green science packs doesn’t necessarily mean I need to spin up more green science machines. The bottleneck might not always be where you think it is; in order to fix the real problem, understanding how to locate the real bottleneck is a good skill to have.

The cause of a bottleneck could be bad design:

Or it could be improper/insufficient input (which could in turn be caused by a bad design elsewhere):

One part of good design is understanding the kind of scale you might have to deal with and reflecting it in your design. This doesn’t mean you have to build something that scales to trillions of nodes today, only that the system you put in place doesn’t prevent you from scaling organically in the near future.

As an example, when I built a new plant in Factorio to produce copper wiring, I didn’t build 20 factories, I started with 2 - but I allowed myself room for 20, in case I needed it in the future. In the same way, you can design with scale in mind without having to boil the ocean and actually build a solution that meets some crazy unrealistic demand on day one.

This blog post is already way too long to talk about proper design, especially considering that this post is fairly technology-agnostic. For now, suffice it to say that having a proper design is important, especially if you’re going in to a new automation project. It’s okay to write some quick prototypes to figure some stuff out, but before you commit yourself to a design, do it on paper (or whiteboard) first. Understanding the steps there will save you a lot of headaches in the long run. Think about the system-to-be using an Algorithmic mindset, and walk through each of the steps in the system to ensure you understand each level.

As the system matures, it’s going to have bottlenecks. That bottleneck might be a human being that still holds power over a manual process you didn’t know existed. It might be an aging service that was written in the 80s. Just like in Factorio, something somewhere will be a bottleneck - the question is, do you know where it is, and is it worth addressing? It may not be. Everything is a tradeoff, and some bottlenecks are tolerable at certain points in the maturity of the system.

The Rule of Autonomy

I am very passionate about this section; here, we’re going to talk about the impact of automation on human beings.

Factorio is a game where you ascend the tech tree towards the ultimate goal of launching a rocket. As the game progresses, and you automate more and more of the system (which you have to do in order to complete the game in any reasonable time), you unlock more and more elaborate and complicated technologies, which then enable you to climb even higher. Building a solid foundation means you spend less time fussing with gears and armatures, and more time unlocking capabilities you simply didn’t have before.

In the “real” world, the idea that automation means human beings are removed from a system is patently false. At first light, automation actually creates more opportunities for human beings because it enables new capabilities that weren’t possible before it existed. Anyone who tells you otherwise doesn’t have a ton of experience in automation. Automation is not a night/day difference - it is an iterative process. We didn’t start Factorio with a working factory - we started it with the clothes on our back.

This idea is well described by Jevon’s Paradox, which basically states that the more efficiently you produce a resource, the greater the demand for that resource grows.

Not only is automation highly incremental, it’s also imperfect at every layer. Everything in systems design is about tradeoffs. At the beginning of Factorio, we had to manually insert coal into many of the components; this was a worthy tradeoff due to the simple nature of the system. It wasn’t that big of a deal to do this part manually at that stage, because the system was an infant.

However, at some point, the our factory needed to grow. We needed to allow the two parts to exchange resources directly instead of manually ferrying them between components.

The Rule of Autonomy is this: machines can communicate with other machines really well. Let them. Of course, automation is an iterative system, so you’ll undoubtedly start out by writing a few scripts and leveraging some APIs to do some task you previously had to do yourself, but don’t stop there. Always be asking yourself if you need to be in the direct path at all. Maybe you don’t really need to provide input to the script in order for it to do it’s work, maybe you can change that script to operate autonomously by getting that input from some other system in your infrastructure.

As an example, I once had a script that would automatically put together a Cisco MDS configuration based on some WWPNs I put into a spreadsheet. This script wasn’t useless, it saved me a lot of time, and helped ensure a consistent configuration between deployments. However, it still required my input, specifically for the WWPNs. I quickly decided it wouldn’t be that hard to extend this script to make API calls to Cisco UCS to get those WWPNs and automatically place them into the switch configuration. I was no longer required for that part of the system, it operated autonomously. Of course, I’d return to this software periodically to make improvements, but largely it was off my plate. I was able to focus on other things that I wanted to explore in greater depth.

The goal is to remove humans as functional components of a subsystem so they can make improvements to the system as a whole. Writing code is not magic - it is the machine manifestation of human logic. For many tasks, there is no need to have a human manually enumerate the steps required to perform a task; that human logic can be described in code and used to work on the human’s behalf. So when we talk about replacing humans in a particular part of a system, what we’re really talking about is reproducing the logic that they’d employ in order to perform a task as code that doesn’t get tired, burnt out, or narrowly focused. It works asynchronously to the human, and therefore will allow the human to then go make the same reproduction elsewhere, or make other improvements to the system as a whole. If you insist on staying “the cog” in a machine, you’ll quickly lose sight of the big picture.

This idea that “automation will take my job” is based on the incorrect assumption is that once automation is in place, the work is over. Automation is not a monolithic “automate everything” movement. Like our efforts in Factorio, automation is designed to take a particular workflow in one very small part of the overall system and take it off of our plates, once we understand it well enough. Once that’s done, our attention is freed up to explore new capabilities we were literally unable to address while we were mired in the lower details of the system. We constantly remove ourselves as humans from higher and higher parts of the system.

Note that I said “parts” of the system. Remember: everything is a system, so it’s foolish to think that human beings can (or should) be entirely removed - you’re always going to need human input to the system as a whole. In technology there are just some things that require human input - like new policies or processes. Keeping that in mind, always be asking yourself “Do I really need human input at this specific part of the system?” Constantly challenge this idea.

Automation is so not about removing human beings from a system. It’s about moving humans to a new part of the system, and about allowing automation to be driven by events that take place elsewhere in the system.

Conclusion

Note that I haven’t really talked about specific tools or languages in this post. It may seem strange - often when other automation junkies talk about how to get involved, they talk about learning to code, or learning Ansible or Puppet, etc. As I’ve mentioned earlier in this post (and as I’ve presented at conferences), this is all very meaningful - at some point the rubber needs to meet the road. However, when doing this yourself, hearing about someone else’s implementation details is not enough - you need some core fundamentals to aim for.

The best way to get involved with automation is to want it. I can’t make you want to invest in automation as a skill set, nor can your manager; only you can do that. I believe that if the motivation is there, you’ll figure out the right languages and tools for yourself. Instead, I like to focus on the fundamentals listed above - which are language and tool agnostic. These are core principles that I wish I had known about when I started on this journey - principles that don’t readily reveal themselves in a quick Stack Overflow search.

That said, my parting advice is:

- Get Motivated - think of a problem you actually care about. “Hello World” examples get old pretty fast. It’s really hard to build quality systems if you don’t care. Get some passion, or hire folks that have it. Take ownership of your system. Make the move to automation with strategic vision, and not a half-cocked effort.

- Experiment - learn the tools and languages that are most powerful for you. Automation is like cooking - you can’t just tie yourself to the recipe book. You have to learn the fundamentals and screw up a few times to really learn. Make mistakes, and devise automated tests that ensure you don’t make the same mistake twice.

- Collaborate - there are others out there that are going through this journey with you. Sign up for the networktocode slack channel (free) and participate in the community.