StackStorm Architecture Part I - StackStorm Core Services

August 28, 2017 in Systems18 minutes

A while ago, I wrote about basic concepts in StackStorm. Since then I’ve been knee-deep in the code, fixing bugs and creating new features, and I’ve learned a lot about how StackStorm is put together.

In this series, I’d like to spend some time exploring the StackStorm architecture. What subcomponents make up StackStorm? How do they interact? How can we scale StackStorm? These are all questions that come up from time to time in the StackStorm community, and there are a lot of little details that I even forget from time-to-time. I’ll be doing this in a series of posts, so we can explore a particular topic in detail without getting overwhelmed.

Also, it’s worth noting that this isn’t intended to be an exhaustive reference for StackStorm’s architecture. The best place for that is still the StackStorm documentation. My goal in this series is merely to give a little bit of additional insight into StackStorm’s inner workings, and hopefully get those curiosity juices flowing. There will be some code references, some systems-level insight, probably both.

Also note that this is a living document. This is an open source project under active development, and while I will try to keep specific references to a minimum, it’s possible that some of the information below will become outdated. Feel free to comment and let me know, and I’ll update things as necessary.

Here are some useful links to follow along - this post mainly focuses on the content there, and elaborates:

- High-Level Overview

- StackStorm High-Availability Deployment Guide

- Code Structure for Various Components in “st2” repo

StackStorm High-Level Architecture

Before diving into the individual StackStorm services, it’s important to start at the top; what does StackStorm look like when you initially lift the hood?

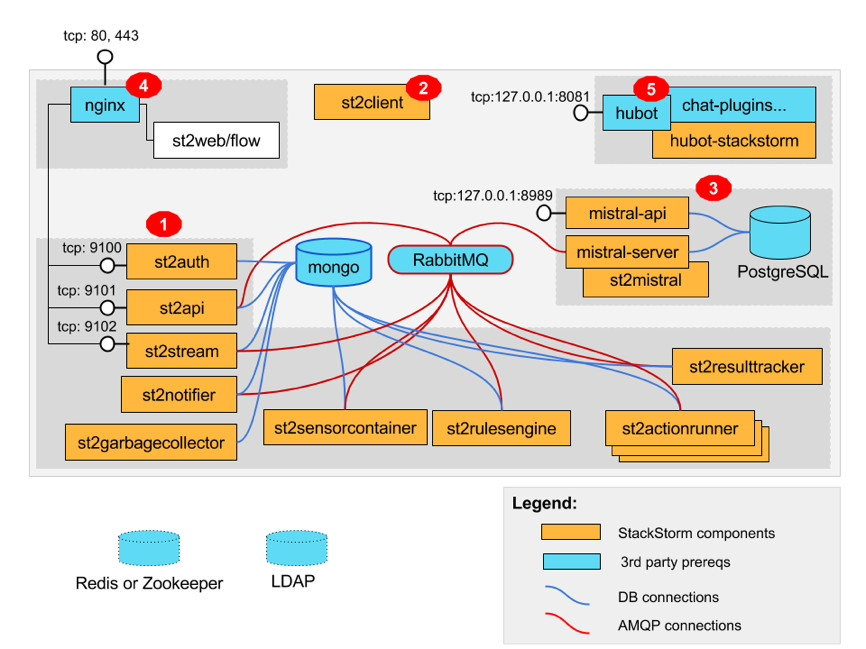

The best place to start for this is the StackStorm Overview, where StackStorm concepts and a very high-level walkthrough of how the components interact is shown. In addition, the High-Availability Deployment Guide (which you should absolutely read if you’re serious about deploying StackStorm) contains a much more detailed diagram, showing the actual, individual process that make up a running StackStorm instance:

It would be a good idea to keep this diagram open in another tab while you read on, to understand where each service fits in the cohesive whole that is StackStorm

As you can see, there’s not really a “StackStorm server”. StackStorm is actually comprised of multiple microservices, each of which has a very specific job to do. Many of these services communicate with each other over RabbitMQ, for instance, to let each other know when they need to perform some task. Some services also write to a database of some kind for persistence or auditing purposes. The specifics involved with these usages will become more obvious as we explore each service in detail.

StackStorm Services

Now, we’ll dive in to each service individually. Note that each service runs as its own separate process, and nearly all of them can have multiple running copies of themselves on the same machine, or even multiple machines. Refer to the StackStorm High-Availability Deployment Guide for more details on this.

Again, the purpose of this post is to explore each service individually to better understand them, but remember that they must all work together to make StackStorm work. It may be useful to keep the diagram(s) above open in a separate tab, to keep the big picture in mind.

We’ll be looking at things from a systems perspective as well as a bit of the code, where it makes sense. My primary motivation for this post is to document the “gist” of how each service is implemented, to give you a head start on understanding them if you wish to either know how they work, or contribute to them. Selfishly, I’d love it if such a reference existed for my own benefit, so I’m writing it.

st2actionrunner

We start off by looking at st2actionrunner because, like the Actions that run inside them, it’s probably the most relatable component for those that have automation experience, but are new to StackStorm or event-driven automation in general.

st2actionrunner is responsible for receiving execution (an instance of a running action) instructions, scheduling and executing those executions. If you dig into the st2actionrunner code a bit, you can see that it’s powered by two subcomponents: a scheduler, and a dispatcher. The scheduler receives requests for new executions off of the message queue, and works out the details of when and how this action should be run. For instance, there might be a policy in place that is preventing the action from running until a few other executions finish up. Once an execution is scheduled, it is passed to the dispatcher, which actually runs the action with the provided parameters, and retrieves the resulting output.

You may have also heard the term “runners” in reference to StackStorm actions. In short, you can think of these kind of like “base classes” for Actions. For instance I might have an action that executes a Python script; this action will use the

run-pythonrunner, because that runner contains all of the repetitive infrastructure needed by all Python-based Actions. Please do not confuse this term with thest2actionrunnerservice;st2actionrunneris a running process for running all Actions, and a “runner” is a Python base class to declare some common foundation for an Action to use. In fact,st2actionrunneris indeed responsible for handing off execution details to the runner, whether it’s a Python runner, a shell script runner, etc.

As shown in the component diagram, st2actionrunner communicates with both RabbitMQ, as well as the database (which, at this time is MongoDB). RabbitMQ is used to deliver incoming execution requests to the scheduler, and also so the scheduler can forward scheduled executions to the dispatcher. Both of these subcomponents update the database with execution history and status.

st2sensorcontainer

The job of the st2sensorcontainer service is to execute and manage the Sensors that have been installed and enabled within StackStorm. The name of the game here is to simply provide underlying infrastructure for running these Sensors, as much of the logic for how the Sensor itself works is done within that code. This includes dispatching Trigger Instances when a meaningful event has occurred. st2sensorcontainer just maintains awareness of what Sensors are installed and enabled, and does its best to keep them running.

The sensor manager is responsible for kicking off all the logic of managing various sensors within st2sensorcontainer. To do this, it leverages two subcomponents:

- process container: Manages the processes actually executing Sensor code

- sensor watcher: Watches for Sensor Create/Update/Delete events

Sensors - Process Container

The process container is responsible for running and managing the processes that execute Sensor code. If you look at the process container code, you’ll see a _spawn_sensor_process actually kicks off a subprocess.Popen call to execute a “wrapper” script:

~$ st2 sensor list

+-----------------------+-------+-------------------------------------------+---------+

| ref | pack | description | enabled |

+-----------------------+-------+-------------------------------------------+---------+

| linux.FileWatchSensor | linux | Sensor which monitors files for new lines | True |

+-----------------------+-------+-------------------------------------------+---------+

~$ ps --sort -rss -eo command | grep sensor_wrapper

/opt/stackstorm/st2/bin/python /opt/stackstorm/st2/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages/st2reactor/container/sensor_wrapper.py --pack=linux --file-path=/opt/stackstorm/packs/linux/sensors/file_watch_sensor.py --class-name=FileWatchSensor --trigger-type-refs=linux.file_watch.line --parent-args=["--config-file", "/etc/st2/st2.conf"]This means that each individual sensor runs as its own separate process. The usage of the wrapper script enables this, and it also provides a lot of the “behind the scenes” work that Sensors rely on, such as dispatching trigger instances, or retrieving pack configuration information. So, the process container’s job is to spawn instances of this wrapper script, with arguments set to the values they need to be in order to run specific Sensor code in packs.

Sensors - Watcher

We also mentioned another subcomponent for st2sensorcontainer and that is the “sensor watcher”. This subcomponent watches for Sensors to be installed, changed, or removed from StackStorm, and updates the process container accordingly. For instance, if we install the slack pack, the SlackSensor will need to be run automatically, since it’s enabled by default.

The sensor watcher subscribes to the message queue and listens for incoming messages that indicate such a change has taken place. In the watcher code, a handler function is referenced for each event (create/update/delete). So, the watcher listens for incoming messages, and calls the relevant function based on the message type. By the way, those functions are defined back in the sensor manager, where it has has access to instruct the process container to make the relevant changes.

That explains how CUD events are handled, but where do these events originate? When we install the slack pack, or run the st2ctl reload command, some bootstrapping code is executed, which is responsible for updating the database, as well as publishing messages to the message queue, to which the sensor watcher is subscribed.

st2rulesengine

While st2rulesengine might be considered one of the simpler services in StackStorm, its job is the most crucial. It is here that the entire premise of event-driven automation is made manifest.

For an engaging primer on rules engines in general, I’d advise listening to Sofware Engineering Radio Episode 299. I had already been working with StackStorm for a while when I first listened to that so I was generally familiar with the concept, but it was nice to get a generic perspective that explored some of the theory behind rules engines.

Remember my earlier post on StackStorm concepts? In it, I briefly touched on Triggers - these are definitions of an “event” that may by actionable. For instance, when someone posts a tweet that matches a search we’ve configured, the Twitter sensor may use the twitter.matched_tweet trigger to notify us of that event. A specific instance of that trigger being raised is known creatively as a “trigger instance”.

In short, StackStorm’s rules engine looks for incoming trigger instances, and decides if an Action needs to be executed. It makes this decision based on the rules that are currently installed and enabled from the various packs that are currently present in the database.

As is common with most other StackStorm services, the logic of this service is contained within a “worker”, using a handy Python base class which centralizes the receipt of messages from the message queue, and allows the rules engine to focus on just dealing with incoming trigger instances.

The engine itself is actually quite straightforward:

- Receive trigger instance from message queue

- Determine which rule(s) match the incoming trigger instance

- Enforce the consequences from the rule definition (usually, executing an Action)

The rules matcher and enforcer are useful bits of code for understanding how these tasks are performed in StackStorm. Again, while the work of the rules engine in StackStorm is crucial, the code involved is fairly easy to understand.

Finally, StackStorm offers some built-in triggers that allow you to trigger an Action based on some passage of time:

core.st2.IntervalTimer- trigger after a set interval of timecore.st2.DateTimer- trigger on a certain date/timecore.st2.CronTimer- trigger whenever current time matches the specified time constraints

Upon start, st2rulesengine threads off a bit of code dedicated to firing these triggers at the appropriate time.

st2rulesengine needs access to RabbitMQ to receive trigger instances and send a request to execute an Action. It also needs access to MongoDB to retrieve the rules that are currently installed.

st2api

If you’ve worked with StackStorm at all (and since you’re still reading, I’ll assume you have), you know that StackStorm has an API. External components, such as the CLI client, the Web UI, as well as third-party systems all use this API to interact with StackStorm.

An interesting and roughly accurate way of viewing st2api is that it “translates” incoming API calls into RabbitMQ messages and database interactions. What’s meant by this is that incoming API requests are usually aimed at either retrieving data, pushing new data, or executing some kind of action with StackStorm. All of these things are done on other running processes; for instance, st2actionrunner is responsible for actually executing a running action, and it receives those requests over RabbitMQ. So, st2api must initially receive such instructions via it’s API, and forward that request along via RabbitMQ. Let’s discuss how that actually works.

The 2.3 release changed a lot of the underlying infrastructure for the StackStorm API. The API itself isn’t changing (still at v1) for this release, but the way that the API is described within

st2api, and how incoming requests are routed to function calls has changed a bit. Everything we’ll discuss in this section will reflect these changes. Pleaes review this issue and this PR for a bit of insight into the history of this change.

The way the API itself actually works requires its own blog post for a proper exploration. For now, suffice it to say that StackStorm’s API is defined with the OpenAPI specification. Using this definition, each endpoint is linked to an API controller function that actually provides the implementation for this endpoint. These functions may write to a database, they may send a message over the message queue, or they may do both. Whatever’s needed in order to implement the functionality offered by that API endpoint is performed within that function.

For the purposes of this post however, let’s talk briefly about how this API is actually served from a systems perspective. Obviously, regardless of how the API is implemented, it will have to be served by some kind of HTTP server.

Note that in a production-quality deployment of StackStorm, the API is front-ended by nginx. We’ll be talking about the nginx configuration in another post, so we’ll not be discussing it here. But it’s important to keep this in mind.

We can use this handy command, filtered through grep to see exactly what command was used to instantiate the st2api process.

~$ ps --sort -rss -eo command | head | grep st2api

/opt/stackstorm/st2/bin/python /opt/stackstorm/st2/bin/gunicorn st2api.wsgi:application -k eventlet -b 127.0.0.1:9101 --workers 1 --threads 1 --graceful-timeout 10 --timeout 30As you can see, it’s running on Python, like most StackStorm components. Note that this is the distribution of Python in the StackStorm virtualenv, so anything run with this Python binary will already have all of its pypi dependencies satisfied - these are installed with the rest of StackStorm.

The second argument - /opt/stackstorm/st2/bin/gunicorn - shows that Gunicorn is running the API application. Gunicorn is a WSGI HTTP server. it’s used to serve StackStorm’s API as well as a few other components we’ll explore later. You’ll notice that for st2api, the third positional argument is actually a reference to a Python variable (remember that this is running from StackStorm’s Python virtualenv, so this works). Looking at the code we can see that this variable is the result of a call out to the setup task for the primary API application, which is where the aforementioned OpenAPI spec is loaded and rendered into actionable HTTP endpoints.

You may also be wondering how st2api serves webhooks. There’s an endpoint for webhooks at /webhooks of course, but how does st2api know that a rule has registered a new webhook? This is actually not that different from what we saw earlier with Sensors, when the sensor container is made aware of a new sensor being registered. In this case, st2api leverages a TriggerWatcher class which is made aware of new triggers being referenced from rules, and calls the appropriate event handler functions in the st2api controller. Those functions add or remove webhook entries from the HooksHolder instance, so whenever a new request comes in to the /webhooks endpoint, st2api knows to check this HooksHolder for the appropriate trigger to dispatch.

st2auth

Take a look at StackStorm’s API definition and search for “st2auth” and you can see that the authentication endpoints are defined alongside the rest of the API.

st2auth is executed in almost exactly the same way as st2api. Gunicorn is the HTTP WSGI server, executed within the Python virtualenv in StackStorm:

~$ ps --sort -rss -eo command | head | grep st2auth

/opt/stackstorm/st2/bin/python /opt/stackstorm/st2/bin/gunicorn st2auth.wsgi:application -k eventlet -b 127.0.0.1:9100 --workers 1 --threads 1 --graceful-timeout 10 --timeout 30st2api defines its own WSGI application to run under Gunicorn.

If you’re like me, you might have looked at the OpenAPI definition and noticed that

st2api’s endpoints are mixed in with the regular API endpoints. At the time of this writing, the two are kept separate when the spec is loaded by either component by none other than…regular expressions! If you look atst2api’s app definition, you’ll notice a few transformations are passed to therouter.add_specfunction. Among other things, these are used within theadd_specto determine which endpoints to associate with this application.

The API controller for st2api is relatively simple, and provides implementations for the two endpoints:

- Token Validation

- Authentication and Token Allocation

As you can see, st2auth is fairly simple. We already learned the basics of how WSGI applications are run with Gunicorn in StackStorm when we explored st2api, and st2auth is quite similar: just with different endpoints and back-end implementations.

st2resultstracker

Due to the available options for running Workflows in StackStorm, sometimes workflow executions happen outside the scope of StackStorm’s domain. For instance, to run Mistral workflows, StackStorm must interact exclusively through Mistral’s API. As a result, after the workflow is executed, StackStorm needs to continue to poll this API for the results of that workflow, in order to update the local StackStorm copy of those executions in the database. Interestingly, the Mistral troubleshooting doc contains some useful information about this process.

A better architectural approach would be to implement callbacks in workflow engines like Mistral that push result updates to subscribers, rather than have StackStorm periodically poll the API. There are a number of existing proposals for doing this, and hopefully in the next few release cycles, this will be implemented, making

st2resultstrackerunnecessary.

The end-goal here is to provide the results of a Workflow execution in StackStorm, rather than forcing users to go somewhere else for that information.

st2resultstracker runs as its own standalone process. When a workflow is executed, it consumes a message from a special queue (note the get_tracker function in resultstracker.py). That message follows a database model focused on tracking execution state, and contains the parameter query_module. If the execution is a Mistral workflow, this will be set to mistral_v2, which causes st2resultstracker to load the mistral-specific querier. That querier contains all of the code necessary for interacting with Mistral to receive results information. st2resultstracker uses this module to query Mistral and place the results in the StackStorm database.

st2notifier

The primary role of st2notifier is to provide an integration point for notifying external systems that an action has completed. Chatops is a big use case for this, but there are others.

At the time of this writing, st2notifier serves two main purposes:

- Generate

st2.core.actiontriggerandst2.core.notifytriggertriggers based on the completion and runtime parameters of an Action execution. - Act as a backup scheduler for actions that may not have been scheduled - i.e., delayed by policy.

st2notifier dispatches two types of triggers. The first, st2.core.actiontrigger is fired for each completed execution. This is enabled by default, so you can hit the ground running by writing a rule to consume this trigger and notify external systems like Slack or JIRA when an action is completed. The second trigger, st2.core.notifytrigger is more action-specific. As mentioned in the Notification documentation, you can add a notify section to your Action metadata. If this section is present, st2notifier will also dispatch a notifytrigger for each route specified in the notify section. You can consume these triggers with rules and publish according to the routing information inside that section.

If you look at the notifier implementation, you can see the familiar message queue subscription logic at the bottom (see get_notifier function). st2notifier receives messages from the queue so that the process function is kicked off when action executions complete. From there, the logic is straightforward; the actiontrigger fires for each action (provided the config option is still enabled), and notifytrigger is fired based on the notify field in the LiveActionDB sent over the message queue.

st2notifier also acts as a rescheduler for Actions that have been delayed, for instance, because of a concurrency policy. Based on the configuration, st2notifier can attempt to reschedule executions that have been delayed past a certain time threshold.

st2garbagecollector

st2garbagecollector is a relatively simple service aimed at providing garbage collection services for things like action executions and trigger-instances. For some high-activity deployments of StackStorm, it may be useful to delete executions after a certain amount of time, rather than continue to keep them around forever, eating up system resources.

NOTE that this is “garbage collection” in the StackStorm sense, not at the language level (Python).

Garbage collection is optional, and not enabled by default. You can enable this in the garbagecollector section of the StackStorm config.

The design of st2garbagecollector is straightforward. Runs as its own process, and executes the garbage collection functionality within an eventlet which performs collection in a loop. The interval is configurable. Both executions and trigger instances have collection functionality at the time of this writing.

st2stream

The goal of st2stream is to provide an event stream to external components like the WebUI and Chatops (as well as third party software).

st2stream is the third and final service constructed as a WSGI application. If you’ve read the section on st2api and st2auth, very little will be new to you here. Searching the OpenAPI spec for StackStorm’s API for /stream will lead to the one and only endpoint for this service.

The documentation for this endpoint is a bit lacking at the moment but you can get a sense for how it works with a simple curl call:

~$ curl http://127.0.0.1:9102/v1/stream

event: st2.liveaction__create

data: {"status": "requested", "start_timestamp": "2017-08-28T21:01:10.414877Z", "parameters": {"cmd": "date"}, "action_is_workflow": false, "runner_info": {}, "callback": {}, "result": {}, "context": {"user": "stanley"}, "action": "core.local", "id": "59a4849602ebd558f14a66d8"}

...This will keep a connection open to st2api and events will stream into the console as events take place (I ran st2 core.local date command in a separate tab to produce this once I had subscribed to the stream).

The controller for this API endpoint is also fairly straightforward - it returns a response of type text/event-stream, which instructs the Router to maintain this persistent connection so that events can be forward to the client.

Conclusion

There are several external services like Mistral, RabbitMQ, NGINX, MongoDB, and Postgres that we explicitly didn’t cover in this post. They’re crucial for the operation of StackStorm, but better suited for a separate post in the near future.

We also skipped covering one “core” service, st2chatops. This is an optional service (disabled by default until configured) that allows chatops integration in StackStorm. There’s a lot to talk about with respect to chatops on its own, so that will also be done in a separate post.

For now, I hope this was a useful exploration into the services that make StackStorm work. Stay tuned for follow-up posts on specific topics that we glossed over for now.