A Guide to Open Source for IT Practitioners

December 20, 2017 in Systems16 minutes

It’s easy to see that open source is changing the way people think about infrastructure. However, as the saying goes: “The future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed”. As is normal, there will always be pockets of IT where active involvement in open source will just take some more time.

I’ve worked on open source for a few years now, and I have always wanted to publish a post that focuses on a few key ideas that I wish I could tell every new entrant into the world of open source. I feel like going in with the right expectations can really help any efforts here go much more smoothly. So if you’re accustomed to getting most if not all of your technology stack from a vendor, and you’re wondering about the open source craze, and trying to make sense of it all, this is for you. My goal with this post is to empower you to start getting out there and exploring the various communities behind the projects you may already have your eyes on.

Open Source is “Free as in Puppy”

Before some practical tips, I want to spend some time on expectations. This is crucially important when it comes to considering open source software for use in your own infrastructure. Obviously, one of the famous benefits of open source is that you usually don’t need to buy anything to get it. It’s “free”, right?

Open source isn’t just about getting free stuff; for enterprise IT, it’s an opportunity to change the paradigm from getting direction from a 3rd party, to being able to set the direction. Everything in technology is based on tradeoffs: “I am willing to give up X to get Y”. While it’s true that you may not have to pay a license fee to use open source software, like you did with vendor-provided solutions, it’s almost certain that some assembly will be required, if not long-term maintenance of the system. There is a financial cost to having your IT staff do this. Even if it’s just a small tool to address a niche use case in your environment, it’s something you’re still on the hook for owning.

It is for this reason I always like to highlight the difference between “product” and “project”. There’s a lot of work that goes on behind the scenes of many vendor-provided products that most open source projects don’t worry about (and rightfully so).

To help mitigate risks in this tradeoff, any major shift to open source will/should include additional headcount. This can include devs to help contribute needed features and bugfixes, but it could also include ops folks to learn it, and keep it running, just like any other piece of infrastructure. I run into all kinds of folks that encounter the inevitable “wrinkles” present in any open source project (even well-funded, corporate-backed ones) and are frustrated it’s not totally turnkey, and bug-free. Most open source projects, in my experience, aren’t trying to be turnkey in the same way we’ve been conditioned with legacy IT vendors. They try to fill a part of the stack, and expect that their community will take the project and piece it together with other components to make a system. So don’t try to half-ass this - if you feel open source is right for a component of your infrastructure, invest in your people and do it right. This is why open source isn’t “free” in the financial sense - your people fulfill some of the role that was previously fulfilled by your vendor support contracts.

In my opinion, open source is all about control. You’re trading off a little bit of that vendor comfort in exchange for enhanced control over the part of your infrastructure where you’re leveraging open source. Open source is a tool to leverage where this additional control gives you a competitive edge, or in some cases, to replace a costly IT system that is not giving you that edge, so you wish to move to commodity. In short, participating in open source isn’t an all-or-nothing proposition - identify areas where internalizing this control might help you gain an edge, and focus there.

If You Want Something, Say Something

Enterprise IT companies have conditioned us to get the vast majority of our technical solutions from behind closed doors. We’re usually forced to adjust to the common-denominator functionality that a particular product or solution provides for an entire set of verticals, and very rarely do we get to significantly influence the direction of a product.

However, open source gives us a unique opportunity to really take an active role in the direction of a project. Note that I emphasized the word “active” - this was intentional. An unfortunately large number of times, I’ve encountered technology professionals who, for whatever reason, choose to watch a project from afar, and not proactively engage with a project. Don’t do this! Understand your use case, and communicate it proactively.

If you “drive by” an open source project on Github - maybe dismissing it because it doesn’t have the nerd knob you think you need - you might be leaving a good solution on the table. Or maybe you don’t think you know enough to jump in - I talk to so many folks that are accustomed to using vendor-provided closed-source solutions exclusively, who feel that they don’t have the “right” or “cred” to post an issue and explain their request or use case.

This couldn’t be further from the truth! The vast majority of maintainers absolutely love helping new users and getting outside perspective on use cases. You have much more direct power to influence an open source project - especially smaller tools or libraries - but it does require active, not passive participation. So if you want something, say something. Doing the “drive by” cheats you out of a potential solution, and the maintainers out of a new perspective they wouldn’t otherwise have.

So to the more practical - how do we do this? Well of course, each open source project is different, but for this post we’re going to focus on Github. It’s generally become the “common ground” for the majority of open source projects today. So, while you will undoubtedly encounter projects that use other tools, even in addition to Github, focusing on this workfow will serve you well for starters. In Github, a “repo” is a place where a project’s code, docs, scripts, etc are stored. This repo might be nested underneath a specific user, or under a separate organization.

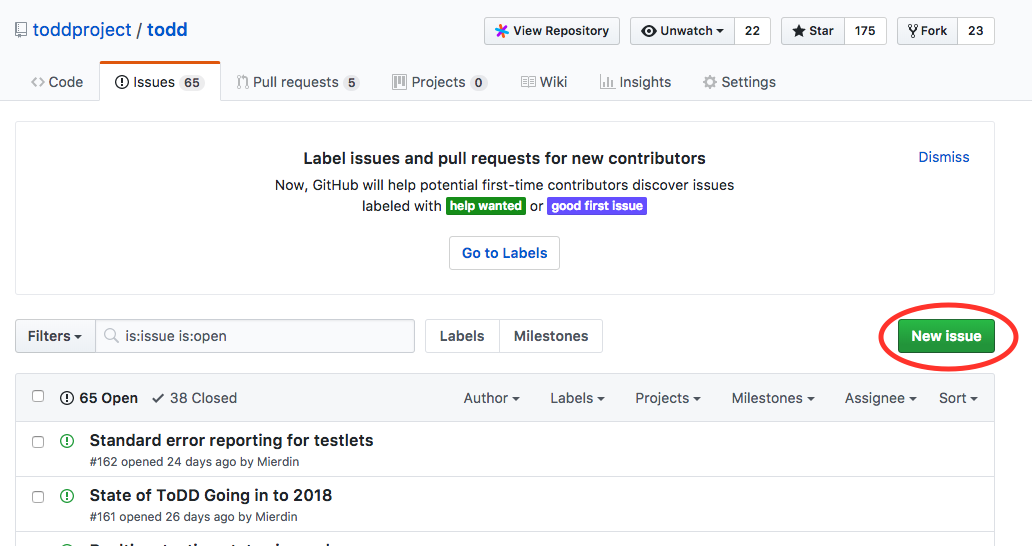

In Github, the best place to go to provide feedback is to create an Issue. Projects that allow this (most do) will have an “issues” tab right on the Github repo. For instance, the ToDD project:

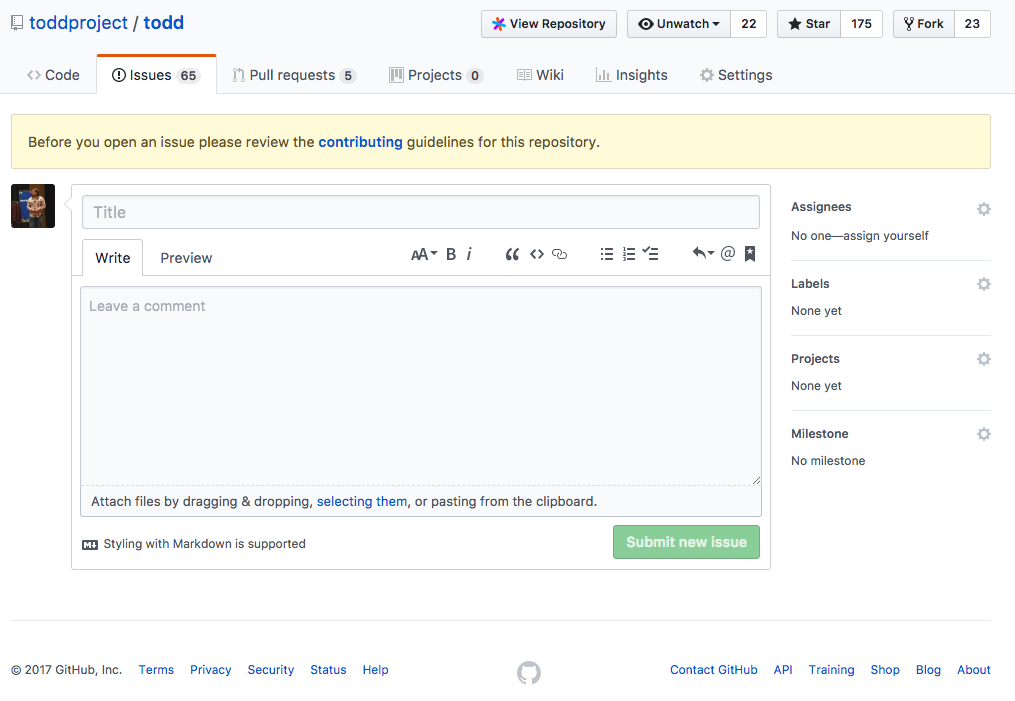

You can peruse the list of existing issues, or use the green “New issue” button to the right. Doing so will open a new form for filling out the title and body of the issue you want to raise with the maintainers:

Note that markdown is supported in the text body. Use this extensively, especially using backticks and triple backticks (`) for readable log messages or code snippets and the like. Those reading your issue will thank you for it.

There are a few things you should do before you open an issue on any project:

- Go with the flow - Get a sense for how the project runs. Many projects will have a

CONTRIBUTING.mdfile in the root of their repository which should contain all kinds of useful information for newcomers, including how to contribute code and create issues. Consider this the README for contributing - go here first. - Do some research - Do some googling, read the project docs, and do a search on the repo for existing issues (both open and closed) to see if the issue you’re about to raise has already been addressed. If you’re encountering an issue, there’s a good chance that someone else did too, and the answer you need might be in a previous issue, or in the documentation. It saves you time by getting the answer without waiting for someone to respond, and it doesn’t require a maintainer to burn cycles sending you back to the docs anyways.

- Bring data - Do your due diligence around gathering logs and error context - everything the maintainers might need to track down the root cause of an issue. Note that the

CONTRIBUTING.mdfile (as well as potentially an issue or PR template) will usually enumerate the details they’ll have to ask you for anyways, so it’s good to have this going in, so you can jump right into fixing the problem, rather than going back and forth for a few days just on data gathering.

Here’s what TO open an issue for:

- Asking for help - You can use issues to ask for help with certain conditions. The docs and previous issues exist for a reason, so don’t open an issue for help unless you have already followed my previous advice and have already exhausted existing resources. Assuming you’ve done this, this is a great way for maintainers to identify blind spots in their docs, so be ready to elaborate on what you’re looking for so that they can add to their documentation.

- Bug reports - If you suspect a certain behavior is a bug, make sure you capture relevant data, and present it openly. It may not be a bug, so be prepared for that.

- Feature requests - Focus on adequately describing your use case, rather than jump to suggesting a solution. Those more familiar with the project will give their perspective on the appropriate solution to match your use case.

The Github UI has a few interesting tools to the right, such as labels and assignments for an issue. In general, stay away from using these - the maintainers will typically have their own triage process, and will assign resources and labels when appropriate.

Here’s what NOT to open an issue for:

- Opinions (negative or otherwise) - Issues should generally be actionable, and able to be closed via a PR. There are times when issues are an appropriate venue for long-form discussion, but be sure this applies to the project in question before using Issues in this way. Most projects have other communication methods for open-ended discussions, like IRC or Slack, and you should be prepared to participate there as well. Usually such resources can be found in the

CONTRIBUTING.mdfile or sometimes theREADME.mdfile.

Assuming you’ve followed the previous points, you may get the response you were hoping for. Or, you may get a response you didn’t expect, such as:

- “That doesn’t really fit with the project, so the answer is no”

- “We like the idea but don’t have cycles to work on this ourselves, so feel free to open a PR”

- “You may be going about this the wrong way, here’s another approach you may not have considered.”

You should be ready for any of these. It’s all part of the flow. Open source tends to be very much about code, about results, not about giving one particular user their way at the expense of the direction of the project - so be ready to have your perspective changed. Make your case based on the data you have, but be prepared to receive new information that might make things different for you.

This is a blessing and a curse - it requires a bit more mental work, but this is all very different from the traditional vendor-led technology discussions, which most customers aren’t able to participate in, certainly not to this level of depth.

Contribute Back

If you follow my advice, and staff your team appropriately, this won’t be hard. Just simply by operating the software, you’ll inevitably start finding your own bugs, or even fixing them. Or maybe you’re just trying to get your feet wet - most repos have a backlog of Issues like bug reports and the like, and can serve as a great source of inspiration for making some of your first contributions to the project.

Easily one of, if not the most valuable technical skills you can have for contributing to open source is understanding Git. Git is a distributed version control system in use by the biggest open source projects in existence, including the Linux kernel itself. It has become the “lingua franca” of contributing to open source. There are numerous tutorials out there for this as a result. For getting started with open source, you should know the basics. Now how to work with a repo, such as clone, push/pull, add/commit, etc. You should understand what branching does.

Shameless plug: we have a whole chapter dedicated to version control - almost totally focused on Git in the hopefully-soon-to-be-released Network Programmability and Automation book.

As mentioned before, Github is a popular platform for collaborating over open source software. Github is one of the most popular SaaS platforms for publicly hosting source code, and as the name implies, it’s built around Git. So, in addition to knowing Git fundamentals, we should also understand how to continue on and use these fundamentals to interact with the Github workflow.

The general workflow for contributing to a repo is via a “Pull Request”. In effect, this is a way of saying “Hey maintainer - I’ve made this change in my own version of your repository, could you please pull it into the main one, so that it’s part of the software going forward?

Each Github repository has a “fork” button near the top. This is just a handy way of making a copy of a given repo that you can make changes to directly. Once you’ve done this, you can then open a PR to “sync” the two copies back up.

A highly abbreviated list of steps for this workflow is below:

- Fork the repo you intend to contribute to. It will ask you where you want to make the copy - doing this under your username is fine.

- Use Git to interact with your fork/copy of the repo. Clone it to your local system, and make the changes. Use

git addandgit commitcommands for this. Then usegit pushto push those commits to your fork. - Github has a really cool feature for detecting when you’ve recently pushed changes to your fork, so if you go to the main repo within a few minutes, it should prompt you to create a PR. If not, you can to to the “Pull Requests” tab to select the target repo/branch and create a PR from there.

Once this is done and the PR is completed, you’ll probably get asked some additional questions, and maybe some additional commits will be required. This is normal - just part of the process. After this process, the maintainers may “approve” the PR, and/or merge it into the target branch (i.e. master).

Try to focus on small, frequent PRs, rather than infrequent, huge ones - especially when getting started. You don’t want to spend 3 weeks on a massive change, only to get feedback that it’s not desired or wanted after all that hard work. Seek feedback before doing a ton of work. You also don’t need to be “finished” with your change to open a PR. It’s not uncommon to make a small change to prototype something, and open a PR before you’re sure it’s a valid approach or before you’ve written tests for the change, all for the purpose of gathering feedback before spending more time on it. Usually projects will have a “WIP” label, or you can just say that you’re not quite finished in the PR description. This is usually not only acceptable, but expected and appreciated.

Some tips for contributing to a project:

- Work from the public project - Don’t fork off permanently and make all your changes privately, behind your firewall. Your bugfixes or enhancements to an open source project are almost certainly not core to your organization’s value proposition. Don’t hoard these and try to maintain your own fork. Just make everything public. There’s no reason to keep most things private, and it will only help to increase your personal value, as you’ll have public contributions to refer to.

- Start small - Most project maintainers welcome PRs, but there’s some relationship building that will go a long way here. Frequent, small PRs as opposed to huge, difficult to review PRs will help the maintainer learn your skills and style, and gain confidence you know what you’re doing. It will also help get your contributions merged in a timely fashion.

- Commit early, and often - Try to keep changes succinct, and don’t be afraid to push your changes early and seek feedback on them, even if you’re not finished. Most projects appreciate you marking PRs with “WIP” or something like that to indicate this.

Finally, any of the responses that I mentioned in the previous section about Issues are also possible with PRs. Be prepared to defend the changes you’ve made, or change your mind about the approach. Again, most maintainers are just trying to keep the project moving forward, and they have a lot of experience with the project, and will help guide you to a solution that works for everyone. Be flexible. Again, smaller PRs will help prevent ugly situations where you’ve silently worked on a PR for 3 weeks but get “shut down” because it wasn’t needed/wanted. Like most things, it’s all about proactive communication.

Open Source is People!

There are generally two types of open source projects:

- Small, individual-led projects that are created out of passion to solve a particular problem

- Medium-to-large projects that have corporate backing, usually as a strategic initiative.

In both cases, every open source project is powered by people like you and I. Even people that are paid to work on a project, usually are doing so because they are passionate about the open source community and are driven by a desire to help other technology professionals. Working in open source carries its own set of challenges, so usually they’re not in it to be supreme overlords to cut you down, but rather interested in fostering a community of diverse perspectives, including yours.

Software development, including open source, tends to give some folks a culture shock at first, since it’s so much about code, and about working solutions. There’s no room for hyperbole, it either works or it doesn’t. So if you’re not accustomed to this culture, know that the person on the other side of a seemingly bad PR review isn’t “out to get you”. Most of the time they’re just being factual. Try to learn what they’re trying to teach you, and remain open to new ways of doing things.

So just remember, there are human beings on the other side of the screen, and while it’s sadly true that there are always bad apples present in all areas of technology, the vast majority just want to build something cool, and work with smart people that give a shit about what they’re doing. By going out of your way to contribute to open source, you’re proving you fit this description, so just focus on jiving with the project and you’ll do fine.

Conclusion

If I could sum this post up with one bit of advice, it’s this: stop sitting on the sidelines, and jump in. Regardless of your background, and regardless of your type of contribution, adding open source to your resume is a huge deal these days. You don’t have to pay to participate; you don’t even have to know how to write code in most cases - many projects will glady accept docs improvements and the like. There’s really no excuse for not getting started.

I hope you all have a Merry Christmas, and a great holiday season overall. Spend time with your families, and when there’s a little downtime (maybe when your family is napping from all the delicious food), consider poking around Github and getting involved with a project.