Beyond "Hello World": Sorting Algorithms in Rust

May 13, 2020 in Rust14 minutes

This year I’ve been picking up Rust as not only a new learning opportunity but also in service to a few side-projects I’ve been getting involved with.

Like a lot of developers, I learn by doing. After spending a few weeks reading the Rust book and watching videos, I looked for some easy project ideas that I could use to explore the language that goes further than a simple “Hello World” which often doesn’t actually give you much breadth at all.

A friend suggested that a useful project might be to implement some popular sorting algorithms. This struck me as a really handy tool when learning any language. Depending on what you are looking at, you’ll need to go beyond simple print statements, and get into iteration, recursion, functions, type definitions, and probably more.

This may not cover even half of the language features, but it’s definitely a better introduction than simply printing something to the screen.

Also, before we get started; this isn’t meant to be a primer on Algorithms. I took a stab at doing this a few years back anyways but also there are a tremendous number of other free resources out there on this. Instead, this is a quick exploration of how I implemented a few common examples in Rust, and a recap of what I learned about the language along the way.

Head over to my GitHub repository if you would like to see (or run) the finished work from the below exercises.

Bubble Sort

Most algorithms courses start with the “bubble sort”. As a refresher, this algorithm works by iterating over the array of values, swapping any pair of values that are not in order. Of course, a single pass is unlikely to sort an entire array the first time, so this iteration happens again and again until the array is sorted. Because of these nested loops, bubble sort works on a time complexity of O(n^2) which is pretty bad. Nevertheless, it’s a simple example to start with and does a good job of showing the impact of a poorly optimized algorithm.

Let’s take a stab at it in Rust.

My first attempt was pretty crappy. It successfully implemented the bubble sort algorithm, but right off the bat, I found myself fighting with Rust’s concept of borrowing (which I am still continually trying to understand), as well as what can’t/cannot be mutable. From my Go and Python experience, my “default” when it comes to loops is the “for” loop, so I attempted to use that here.

This decision had a nasty ripple effect that forced me to make other bad decisions just to get the code to compile:

- Making changes to a vector while iterating over it wasn’t possible, so I created

vec_mutvia thevec.to_vec()function, creating a mutable copy. I originally placed this at the top of the function, outside the loop. - Having the creation of

vec_mutoutside the loop gave me a “value moved” error, which I’ll discuss further down. The only way I could get this to work was if I moved this inside the loop, which is obviously inefficient and pointless, but it worked. - I had originally declared

vec, the input parameter for this function, as immutable (simplyvec: Vec<i32>). The reason I was creating a copy of this was so that I could have a mutable copy that I could swap elements on. I had hoped to be able to returnvec_mutfrom this function, but that wasn’t possible because as mentioned above, this had to be declared within the function, and wasn’t accessible outside this scope. This meant that I had to dovec = vec_mut;, which of course meant thatvechad to be mutable (in retrospect, I probably could have returnedvec_mutfrom within the outer loop instead ofbreaking, but that has its own problems and is a pet peeve of mine).

Yuck. Here’s the functional-but-ugly result in all its glory:

1fn bubble_sort(mut vec: Vec<i32>) -> Vec<i32> {

2

3 loop {

4

5 // We can't change items of a vector while iterating, so let's create

6 // a copy of it first, and we'll make changes here while iterating over

7 // the immutable original

8 let mut vec_mut = vec.to_vec();

9

10 let mut swapped = false;

11

12 let mut i = 0;

13 for _item in vec.iter() {

14 if i >= vec.len()-1 { break; }

15

16 if vec[i] > vec[i+1] {

17 swapped = true;

18 let value = vec[i];

19 vec_mut.remove(i);

20 vec_mut.insert(i+1, value);

21 break;

22 }

23 i += 1;

24 }

25

26 vec = vec_mut;

27

28 // no swaps? Then we're sorted

29 if !swapped { break; }

30 }

31

32 vec

33}As mentioned above, creating the vec_mut copy outside the loop proved impossible, as the compiler was giving me the following errors:

1RUST_BACKTRACE=1 cargo run --example bubblesort

2 Compiling rust-algorithms v0.1.0 (/home/mierdin/Code/rust-algorithms)

3error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `vec_mut`

4 --> examples/bubblesort.rs:36:17

5 |

620 | let mut vec_mut = vec.to_vec();

7 | ----------- move occurs because `vec_mut` has type `std::vec::Vec<i32>`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

8...

936 | vec_mut.remove(i);

10 | ^^^^^^^ value borrowed here after move

11...

1243 | vec = vec_mut;

13 | ------- value moved here, in previous iteration of loopDue to the way I was assigning vec_mut back to vec, I was moving ownership of the value to vec, instead of making a copy. This meant that at the next loop iteration, I was no longer able to remove values from vec_mut. If I wanted to, I could have made another copy with vec = vec_mut.to_vec(); instead, but then I’m making copies of copies, and this is already out of control. Technically, this was also happening while I had the vec_mut creation inside the outer loop, but in this case, the ownership was re-set, and I was able to remove values from it again, which is why this worked. It was masking my poor assignments of ownership.

So, by now I’m sure I’ve convinced you that I’m capable of writing bad Rust. Let’s move on.

Simply using a while loop with a counter simplifies things quite a bit. I know that in many cases, using the for loop as before helps avoid things like index out-of-bounds errors, but in this case I think it’s worth the simplicity. With this, I still have to pass in vec as mutable, but since I’m not iterating over it, I can perform the necessary swaps on it directly, and return the result when finished.

1fn bubble_sort(mut vec: Vec<i32>) -> Vec<i32> {

2 loop {

3 // Default to false, so we know by the end if we had any swaps,

4 // which indicates we need to do another pass

5 let mut swapped = false;

6

7 // Iterate over the length of vec, swapping any values that are out of order.

8 let mut i = 0;

9 while i < vec.len() {

10 if i >= vec.len()-1 { break; }

11 if vec[i] > vec[i+1] {

12 swapped = true;

13 let value = vec[i];

14 vec.remove(i);

15 vec.insert(i+1, value);

16 break;

17 }

18 i += 1;

19 }

20

21 // no swaps? Then we're sorted, and we can exit and return the final `vec`

22 if !swapped { break; }

23 }

24

25 vec

26}Implementing this algorithm gave me real, rusty experience with:

Not bad for one of the simplest sorting algorithms out there. Let’s move on to something a little more complicated (and efficient).

Merge Sort

I also wanted to tackle “merge sort”, mostly because it’s one of my favorites. In addition to being way more efficient than bubble sort, I just like the way that it works.

The “divide and conquer” nature of merge sort means that we use recursion to divide the problem into smaller and smaller sub-arrays to the point where they only have one element, and are therefore, sorted. Producing a final sorted array is all about merging these smaller arrays into bigger ones until finally we have one big sorted array that’s the same size as the unsorted one we started with. Merging these sub-arrays is done by taking the smaller value from the beginning of each array and progressing through them until there are no more values.

I think that’s what I like about merge sort - we break the problem down until a fundamental truth becomes inescapable (that the two arrays are sorted), and we merge them back together using a process that exploits and is entirely predicated on this truth. I’ve always found that to be a very elegant and even beautiful way of solving the problem.

Anyways, regardless of language, the very first thing you want to do is detect if the incoming array (in our case, a vector) only has a single element. If so, we can return right away, since there’s no more dividing to do; at that point it is time to conquer.

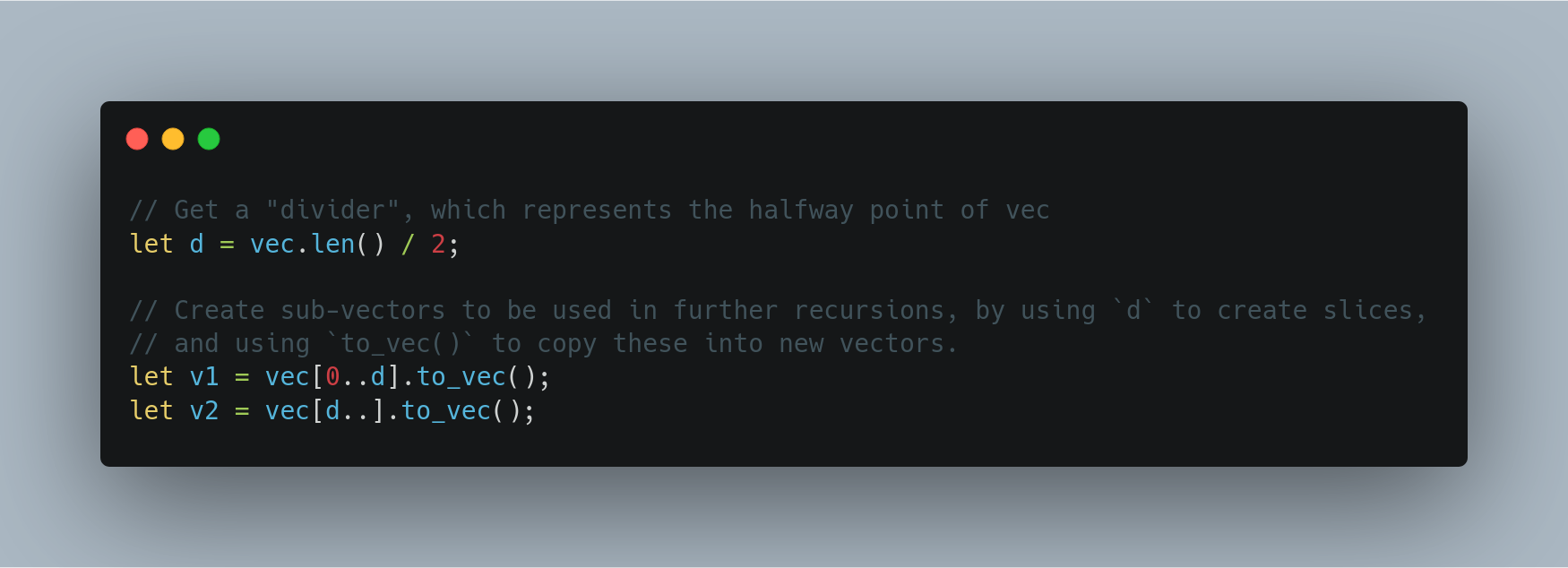

Assuming we’ve moved past this, we know our vector contains at least two elements, which means we can split it up into two “sub-vectors” as part of the “divide” part of our strategy.

I declared d to be set to the result of dividing the length of our input vector vec by 2. The quotient for this operation is an integer that has been floored, meaning if there was a remainder, it is dropped, and we’re left with the lower integer value.

So, if our length is 4, d is 2. If the length is 5, d is still 2.

I had originally casted d to an integer, expecting this would result in a floating-point type, but this caused problems when using d in the above slices, as this notation expects a type called usize type. It turns out that without a cast, the division operation above also returns a quotient with type usize, so that’s why I’m able to use it directly as above. From my limited understanding, usize is similar to integers, but their capacity is based entirely off of the computer architecture (i.e. 32 vs 64 bit), whereas types like u32 and u64 obviously have set sizes.

I’ll be digging into this in the future - I’ve noticed this is heavily used throughout Rust and the standard library, so I’m assuming there’s a reason for this as opposed to using predictable types. If you have any useful pointers here, hit me up

Now that we have our “sub-vectors”, we can recurse into our sort function. The syntax for this is as expected, though its important to highlight that the example below effectively overwrites the un-sorted v1 and v2 with their sorted counterparts derived from merge_sort.

At this point we can treat v1 and v2 as sorted vectors, but we still have to merge them together into a single vector, ensuring that this final product is also sorted. To start, I created a vector called retvec, which I meant to be empty to begin with, but that I would push values into them as I iterated over v1 and v2.

1let mut retvec = Vec::new();What happened next was really interesting. This syntax is actually valid, but the Rust compiler isn’t happy with this statement on its own; we also need to push values into the vector, which I hadn’t gotten around to doing at the time.

1RUST_BACKTRACE=1 cargo run --example mergesort

2 Compiling rust-algorithms v0.1.0 (/home/mierdin/Code/rust-algorithms)

3error[E0282]: type annotations needed for `std::vec::Vec<T>`

4 --> examples/mergesort.rs:34:21

5 |

634 | let mut retvec = Vec::new();

7 | ---------- ^^^^^^^^ cannot infer type for type parameter `T`

8 | |

9 | consider giving `retvec` the explicit type `std::vec::Vec<T>`, where the type parameter `T` is specifiedAs soon as I continued with my implementation, and started pushing values into the vector, the Rust compiler stopped complaining, since pushing a value implicitly told Rust that we wanted a certain type for these vector elements (in this case, the integers from v1 and v2). I could have also done what the compiler asked, and set the type myself with let mut retvec: Vec<i32> = Vec::new();, but struggling briefly here reminded me that I had an opportunity to be more Rusty.

One thing I like about Rust is that it tends to encourage you to be mechanically sympathetic - that is, working with the underlying hardware, not against. Sometimes this are enforced by the compiler, other times it’s strongly suggested by convention or the tools available in the language. While we certainly could create an empty vector and “push” to it when we have a new value ready, doing so can often result in extremely inefficient memory allocations. Rather than growing the vector one value at a time, in this case we actually know exactly how large retvec will become: the sum of the lengths of v1 and v2!

1 let size = v1.len() + v2.len();With this, we can use the vec! macro to create a vector with the exact size we want. This means that at runtime, we will only be requesting a memory allocation for this vector once, and that allocation will be sufficient throughout the lifetime of this function call. We are also passing in 0 to this macro to pre-populate every index with a value of 0, but we will overwrite each of these with appropriate values during the merge.

Note that we could have also used

Vec::with_capacity(size);to accomplish the same goal. If using this, then you will still need to ensure you’re usingretvec.push()to push values to the vector (which again, also sets the type for the vector values). I chose instead to pre-populate with zeroes using thevec!macro, and setretvecvalues via index, managed by a counter variable. Either way seems to work just fine, the important thing is that we’ve only done a single memory allocation up-front.

Remember, a key aspect of the merge sort is that we can safely assume v1 and v2 are already sorted by this point. It is because of this fact that we can perform the simple merge logic below. Since we know the smaller values are already at the beginning of each vector, we simply step through each, one index at a time. We take the smaller of the two, increment the relevant counter, and add that value to the next index of retvec. At the end, retvec will also itself be sorted.

Finally, add all remaining values. Only one of these blocks will actually run (since the previous loop wouldn’t have ended unless one of the counters had reached the length of the corresponding vector). Also, since we’ve been comparing values in the previous loop, we can safely assume that whichever vector has remaining values to use is sorted, and also contains values that are larger than anything from the other vector. So we just iterate through them and append them to retvec.

At this point, retvec should represent a combined, sorted vector, that we can return.

Implementing this algorithm gave me real, rusty experience with:

- The

usizetype - Recursion

- Mechanically sympathetic memory allocation

Conclusion

I’m not sure if I’ll continue this series, as I have other subprojects to take me deeper, not only into Rust, but also other subjects. For now, this was a really fun introduction and gave me some real experience with Rust, and started building the muscle memory. So much of what I think forces people to shy away from new languages is just that they don’t know it yet.

I still feel very uneasy working with Rust, but I know it’s because the language is still very new to me. However, I feel much more confident than I did earlier in the year, and I am reminding myself that I felt the exact same way about Go and even Python back when I started learning those. Examples like these allow me to force myself to move past this fear, and start to develop the familiarity that’s needed to really be productive. Reading and watching videos is important to start, but at some point you just have to start getting your hands dirty.

I hope this was helpful to you as well!