What Is Generic Programming?

August 4, 2020 in Programming14 minutes

This year, my journey to learn Rust (and actively use it in a few side projects) has been a treasure trove of learning experiences. Lately, I’ve been finding myself trying to wrap my head around not just new syntax, but entirely new software programming paradigms that I simply haven’t been exposed to before.

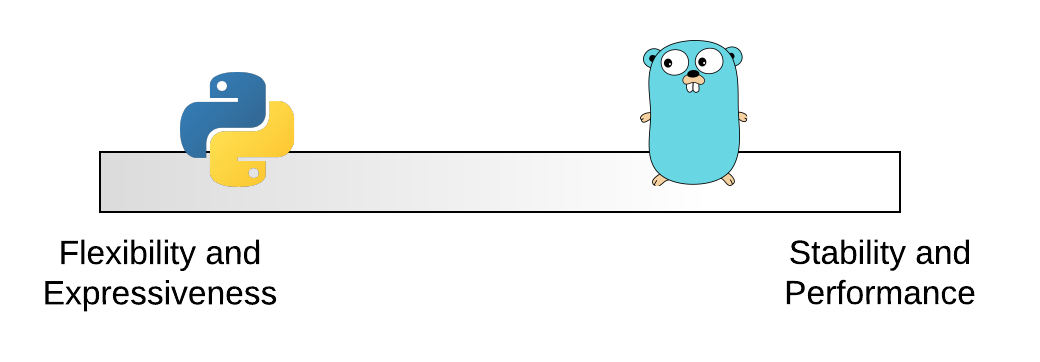

In my career thus far, I’ve mainly used two languages professionally: Python, and Go. It turns out this forms a pretty interesting story arc, since these two languages paint a wide spectrum of approaches to enabling the developer to be expressive and productive while managing the runtime tradeoffs of doing so. I am finding very clearly that outside the scope of these two languages, which dominate my experience thus far, one of the ways that some other languages (particularly systems languages) deal with this is through something called generic programming.

While exploring any new topic, I strive to understand the problem domain they (or one of their features) are intended to tackle. Often, I feel like I don’t really understand the topic until I’ve spent some time understanding what life is like without that solution. So, before getting into generic programming itself, I find it useful to explore the two languages I’ve primarily used in the past, and articulate how they solve certain problems. Hopefully this will make it clear where I’m coming from, while also setting the stage to truly understand the value of what we’ll discuss afterwards.

A Tale of Two Languages

One of Python’s strengths is that it’s very easy to quickly get the functionality you want. This comes from its inherent flexibility. Consider the following function for adding two numbers together:

def addnumbers(a, b):

return a + bThis takes very little time to create, because we don’t have to fuss around with defining which types we want to be able to pass in. Note that I used the term “number” - not “32-bit integer”, or “64 bit float”. This is because - without any extra effort on my part to enable this - any types that can be added together using the + operator are fair game here.

>>> addnumbers(1, 2)

3

>>> addnumbers(1, 3.3)

4.3What’s more is we don’t have to declare the function’s return type either. The type that is returned from this function (and indeed the fact that it returns anything at all) depends on the usage of the return keyword. The positive result of this is that we can write a single function to take care of a wide variety of use cases, and do it quickly.

However, while Python is dynamically typed, it is also strongly typed. Which means if you accidentally passed in a string (say you forgot to cast to int somewhere) for one of these parameters, you get a runtime failure:

>>> addnumbers(1, "foo")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 2, in addnumbers

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'I’m aware that Python is supported by numerous implementations. In this post, however, I am referring to “cpython”, as it is the reference implementation, and overwhelmingly the most widely used option.

The primary reason this is possible, is that Python has no built-in type checking. As long as a given Python program is syntactically valid, it will run, and issues like this will only surface at runtime. This forces the developer to ensure there is error handling in place to deal with such errors, and even with this, a common best practice is to use type hints combined with third-party linting tools to try to stay on top of issues like this. In general, much of Python’s flexibility comes from its intentional decision to do more work at runtime. Because of this, the tradeoff (which may be acceptable/manageable to you) is a slower, and more fragile runtime experience.

Go, on the other hand, is not a dynamically typed language. If you wanted to implement the above function, you would have to not only declare the type of each parameter, but also declare the return type, all very explicitly:

func add(x uint32, y uint32) uint32 {

return x + y

}The benefit of doing this in a statically typed language is that the compiler does a lot more work to ensure that any code that calls this function is passing in the correct types. So, as long as we always call this function with 32-bit unsigned integers, we can build this code and ship our program:

add(4, 6)However, if we try to pass in, say, a negative integer (not supported by unsigned integer types), we get a compile error:

add(-2, 6) ❯ go build ./cmd/...

cmd/generics-go/main.go:6:16: constant -2 overflows uint32Some who are accustomed to languages like Python are pretty quickly turned off by this (I was one of them when I started). However, it takes very little time to become accustomed to this, and the net benefit is that as long as your code can compile, you can be assured that some of the more basic type issues don’t exist.

Because of this, our function really shouldn’t be named add, but rather add_uint32, because it will really only work for that type. So, the question becomes, what if we want to be able to add multiple types of numbers? We’ll need to write each function ourselves:

func add_uint32(x uint32, y uint32) uint32 {

return x + y

}

func add_int32(x int32, y int32) int32 {

return x + y

}

func add_int64(x int64, y int64) int64 {

return x + y

}

func add_float64(x float64, y float64) float64 {

return x + y

}It’s worth noting that the Go community is currently looking at solving this problem, perhaps by adopting techniques similar to those that will be discussed in this post. However, historically, the position of Go has been that “a little copy and paste never hurt anybody” - in other words, this may be a little more verbose than we’d like, but the tradeoff is that we get much more predictable, stable, performant code as a result. This historical attitude - something that any Go developer for the past decade would be accustomed to - is what I’m referring to.

Go does have one tool to make things a little more flexible here, called the “interface”. Much like traits in Rust, interfaces are a tool to offer a way to represent a set of behaviors (methods) that can be implemented by a concrete type (like a struct). However, this doesn’t quite go so far as to let us do things like consolidating the above functions into a single one, regardless of type. When used idiomatically, interfaces are a great tool, but really aren’t intended to solve this problem and do not allow us to build functions that are truly agnostic of concrete types at development time.

As you may suspect, there is a ton of detail we could get into here, but I will leave it at this for now, as this is a pretty deep rabbit hole into subjects I would like to cover in another post.

So it seems like we have some kind of spectrum between two diametrically opposed outcomes that we must choose between. Languages like Python are very flexible, but include a significant penalty to runtime performance and overall stability. Go on the other hand, (when used in alignment with the idioms of the language) sacrifices a lot of this flexibility, forcing the developer to do more work up-front, but rewarding them with much more stable, performant software.

This is of course, a huge generalization, and there are plenty of other languages that do fit in somewhere on this spectrum that I don’t have much experience with. However, this comparison is interesting to me personally because these are the two languages I happen to have selected for my early software career, yet they seem to approach this problem in very, very different ways.

What Is Generic Programming (And Why Should I Care)?

Given these two extreme examples, you might be wondering how we might be able to get the best of both worlds. How can we obtain the development-time flexibility and expressiveness of a language like Python, while simultaneously retaining the run-time benefits of a statically and strongly typed language like Go?

Generic programming is a way that some languages have offered a solution to do exactly this. You may also hear this referred to as parametric polymorphism, “parameterized types”, or “templates”. All of these are different ways of accomplishing this two-fold benefit.

You may also see the term “generics”, as a way of describing specific entities or features within a language that facilitate generic programming. I’m choosing to often use the phrase “generic programming” as a verb or action explicitly because this carries much more meaning for me as a way of programming, because that’s really what it is. This subtle change in wording really helped me understand the purpose behind adding generic programming capabilities to any language, and what it gives us as developers.

Imagine if you were tasked with explaining - verbally - the example function from the previous example. How might you explain it using plain language? It’s unlikely that you would explain each function individually. Humans are great at seeing patterns, and the vast majority of us would look at those four functions and simply say something like “these functions each take two numbers of some kind, add them together, and return the resulting number”. In this case, we’re really treating the word “number” as a placeholder; we’re not using the term to describe a specific concrete type, but rather as an abstract type of data that each function will treat equally.

Generic programming allows you to do exactly this in code, but without sacrificing the inherent safety of a statically typed language. It gives us primitives to declare “placeholder types” that allow us to focus less on the specific types that may be used or declared by other portions of the codebase, but rather focus on these higher-level patterns that can be consolidated into simpler declarations.

To enable generic programming, a language must do two things:

- Syntax - Provide a syntax whereupon generic terms can be declared and used in functions, fields, etc.

- Implementation - Perform additional steps at compile-time to render generic terms into the necessary concrete, specialized entities.

In the sections to come, we’ll briefly explore these two aspects of generic programming. However, note that I am intentionally keeping details light, as we’re really not talking about any specific language in this post, so details will of course vary based on the language you choose to use. I’ll be exploring generics in Rust in a future post, where we can get into much more detail.

Syntax

Of course, we first need a syntax that we as developers can use to express our intent using generic, abstract means. Consider the Python example from before:

def addnumbers(a, b):

return a + bThe reason this was so powerful was that we as developers don’t have to worry while we’re writing this code about specifying which type a or b is, but rather expressing the more generic intent of the function: add two numbers together. To me, this underscores the real spirit of generic programming. It’s the ability for us as developers to dwell less on specific types, and instead focus on the relationship between values. Consider this pseudocode function signature:

function foobar(x: T, y: U) UHere, we don’t really know or care while writing this function what “type” x or y are. What we do care about is that x and y are not the same type, as denoted by the fact we’re using different generic parameters - T and U - for each. We also do care that the return type is the same as whatever type y is, as both of those use the generic parameter U.

As a slightly different example, say we wanted to write a function where we ensured the two function parameters were the same type, but the return type was something different. This might look like:

function foobar(x: T, y: T) UGeneric parameters like T and U as used in these examples, allow us to put specific, concrete types out of our mind for the time being, and instead convey intent about the relationships between types when used here. It’s about letting go of the specifics, and instead focusing on the general “shape” of these function signatures, and how their input and output values relate to each other.

As you can see, despite being generic placeholders, these generic types do still serve as a set of constraints for what types can be used. When the code is compiled, any calls to these functions are checked against these constraints and deviations result in compilation failure, which is a good thing.

Many languages provide other tools to place further constraints on what types can be used in lieu of generic types like this as well. Rust has traits, and the latest proposal for adding generics to Go leverages interfaces for this purpose. In most cases, this just adds more compile-time checks, and doesn’t influence the runtime behavior of our code. This allows us to leverage the inherent flexibility of generic programming, but still control what is used to some extent.

Implementation

Of course, syntax is not the whole story when it comes to generic programming. It must be coupled with an underlying implementation that makes it possible. As with many other things, compiled, statically typed language implementations are tasked with translating the original intent we as developers convey with this syntax, into something that can execute safely and quickly. The process of monomorphization is how many languages are able to make this guarantee.

“Monomorphization” is a relatively modern term, but “reification” has also been used for decades. Regardless, as it pertains to generic programming, this is the automated expansion of generic terms into as many concrete terms as are needed at compile-time. This allows us to use generic, abstract terms during development, but the final compiled program has all of the stability and speed as if we’d used concrete types in the first place.

The process is actually quite simple. Imagine our previous pseudocode example:

function foobar(x: T, y: U) ULet’s say in the rest of our code, we call this function two different times:

a = foobar(1, 3.2)

b = foobar(5.4, 99)The compiler will “monomorphize” our generic function into two separate functions that match the types we specified when invoking these functions:

function foobar_int32_float32(x: int32, y: float32) float32

function foobar_float32_int32(x: float32, y: int32) int32Remember the Go example from earlier in this post? This is basically what monomorphization gets us. Here, we get to experience the flexibility of being able to use generic terms, as we did in Python, but rather than moving the consequences of that flexibility to runtime, the compiler automatically renders out concrete versions of them. The final compiled program contains no generic terms at all, and retains all of the benefits of speed and stability that this brings.

The Sweet Spot

The process of monomorphization does result in slightly larger binaries as well as longer compile times (since the compiler is essentially copying/pasting code for you under the hood, which takes space and time to do). Both of these are true, and should be taken into account. However, in my opinion, there’s a more important consideration and that has to do with developer productivity.

Generic programming is itself a developer productivity tool. However, so is Red Bull, and it turns out that too much of either can have the opposite effect than intended. Similarly, generic programming isn’t something you should reach for at every opportunity. It can definitely have the byproduct of making code harder to understand, especially if what it is trying to abstract is relatively simple.

However, generic programming can really help when:

- You intentionally don’t want to know the types that will be handled by your code. Again, this is a very valid approach for maintainers of libraries and APIs.

- A certain piece of functionality is inherently very complex, and maintaining this using concrete types is untenable. For these, generic programming coupled with further constraints like traits or interfaces can help keep things manageable.

That said, principles of iteration and “good is better than perfect” apply here, as they do in most areas of software development. While refactoring your code, consider generic programming’s benefits and drawbacks alongside the idioms and specific implementation your language employs.

That’s it for this post - next, I’ll tackle the use of generic programming specifically in Rust, so stay tuned!