Introduction to eBPF

January 19, 2021 in Programming16 minutes

If you’re paying much attention at all to the systems or cloud-native communities, you have certainly heard about eBPF. It has dominated several conference schedules for the last few years, and it even has its own conference now! However, unlike a lot of hyped-up technology buzzwords, this one’s momentum doesn’t seem to be unwarranted, or even ahead of the curve:

“BPF is not someone’s academic paper. BPF is not a “proof of concept”. BPF is running in production” –Brendan Gregg

I’d characterize the community around eBPF to still be fairly small, and highly pragmatic. After researching this topic, I think it’s an important technology to be aware of, but how it applies to you depends wildly on your skills and your role as a technologist.

eBPF itself as a topic is huge, and there is a multitude of resources out there that dive into the specifics, many of which I’ll link to below. Please check out those external resources - I couldn’t possibly improve on them. I’m writing this post primarily as a way to kick off my eBPF learning journey, but also to pursue answers to the following questions:

What problem was eBPF created to solve, and why is it a better model than some of the existing alternative approaches?

How does eBPF work, and how can we use it to build applications that fit within this new architecture?

Who should care about eBPF, and for what reasons?

Why We Use Operating Systems

Operating systems give us a lot to build on top of. The tradeoff is that you have to play by their rules. If for instance, you want to send some packets over the network, you don’t access the NIC directly; rather you have to work through the API that sits on top of the underlying kernel, using a mechanism typically referred to as “syscalls”. The applications you use every day, even the very browser you’re using to read this post right now is leveraging a similar API. This creates a clear demarcation between the space where our apps run (userspace) and the space where the operating system internals and hardware interactions take place (kernel space). In fact, operating systems often partition system memory so that the two are kept separate from each other.

This paradigm is extremely helpful - it’s not safe or feasible to expect every application in the universe to be able to work with every type of hardware in existence, and also coexist with each other without crashing the system. However, this comes with some tradeoffs. The two big ones are as follows:

When your application requests something from the kernel, often a chunk of data in kernel space needs to be copied into userspace. We need to do this because operating systems strictly partition regions of memory used for the kernel, so it’s not possible to simply give a userspace program a pointer to some region of kernel memory. This is commonly referred to as “crossing the user/kernel boundary”, and because of this copy operation, operations like these can have pretty significant performance implications.

Like all abstractions, the programmatic interface provided by an operating system via syscalls results in a certain loss of context. You cannot freely access resources in kernel space, you can only work with what you’re given. Similarly, you cannot just walk into a restaurant’s kitchen and start making food - you have to order from the menu, and this keeps a large chunk of the experience out of your hands.

For the sake of this article, we’ll be focusing only on Linux, but many of the same traits discussed here apply to other operating systems.

Linux is optimized for being an end-device, and working with large packets, not so much for packet forwarding/decisions and lots of small packets. This is a big reason for Linux’s reputation as a very poorly performing substitute for the big ASIC-driven machines that most IT shops and service providers are accustomed to. One reason for this is the penalty of crossing the userspace boundary. For traffic that cannot be handled purely by the kernel, the entire packet must be copied into the memory space available to a userspace process, which means each packet incurs a performance cost, and the more packets you have to receive, make decisions on, and forward, the more this cost becomes apparent.

The attempt to use Linux as a full-blown networking platform, therefore, has resulted in three distinct approaches, each of which has some significant tradeoffs:

Traditional Approach - an application that sits in userspace, leverages syscalls, etc to work with the kernel. This is the “traditional” approach because you’re using each part of the system the way it was intended, but as we’ve discussed, for some use cases like network forwarding, there can be severe performance and loss-of-context penalties. A lot of higher-level network service applications like load balancers and intrusion prevention systems work this way.

Do Everything in Userspace - rely on the kernel for nothing, and reinvent all the wheels (aka “have fun writing your own TCP stack”). This is the approach taken by Intel’s DPDK.

Kernel Modules - add the functionality you need to the kernel by writing a module. There’s no userspace boundary crossing here, and you have access to everything you need, all the way down to the hardware. This is the approach taken by Juniper Contrail as an example. Unfortunately, when working purely in kernel space as you are with kernel modules, there’s no hard boundary or API guarantees, like there is with the userspace boundary. Also, the blast radius for when things go wrong is system-wide; you can cause security issues, or crash the entire system. Finally, each new Linux kernel version brings the very real possibility of breaking changes, so that a kernel module must be refactored to be compatible. So this approach is extremely fragile.

eBPF gives us a fourth option. But before we get there, we need to discuss a little history.

Berkeley Packet Filter

The origin story of eBPF lies in it’s first, more narrowly-focused implementation known at the time as Berkeley Packet Filter. This was a new architecture that allowed systems to filter packets well before they were further received by the kernel - or worse - copied into userspace. In addition, this made use of a new register-based virtual machine, with a very limited set of instructions, that could be provided by a userspace process. This meant that utilities like tcpdump could compile very simple filtering programs (influenced by more human-readable filter strings provided by the user via command-line) that ran entirely in kernel space, without the need for kernel modules.

The tradeoff here was that you can “program” the kernel to filter certain packets without having to consult a userspace process for these decisions - all without using kernel modules - but the tools you have to make decisions are fairly limited to the instructions available to you in the BPF virtual machine. This limitation is done to ensure the safety and stability of the kernel. You get the performance of running entirely in kernel space, but you have to play by the rules of the BPF compiler.

A fun exercise is to run tcpdump with the -d flag to see the resulting BPF program that is compiled on your behalf, and sent to the kernel for execution.

~$ tcpdump -i wlp2s0 -d 'tcp'

(000) ldh [12]

(001) jeq #0x86dd jt 2 jf 7

(002) ldb [20]

(003) jeq #0x6 jt 10 jf 4

(004) jeq #0x2c jt 5 jf 11

(005) ldb [54]

(006) jeq #0x6 jt 10 jf 11

(007) jeq #0x800 jt 8 jf 11

(008) ldb [23]

(009) jeq #0x6 jt 10 jf 11

(010) ret #262144

(011) ret #0I highly recommend reading the original BPF paper, as it discusses these ideas quite well.

Enter: “eBPF”

The “elevator pitch” you’ll hear about eBPF (“extended BPF”) is that it does to the kernel what Javascript did for HTML. The Linux kernel is mostly presented “as is” - in that you have a surface area you can interact with via syscalls, and that’s about it. This may be fine for some applications, but for others, this is a pretty significant constraint that warranted some of the workarounds we discussed in the sections above. eBPF expands on the original architecture behind classic BPF by providing a set of tools for writing fairly generic programs that are run purely in kernel space, safely, and with a suite of other tools to complete the picture.

eBPF is the result of many improvements and enhancements to BPF, stretching back to 2014, turning it into a much more capable and robust method of programming the kernel. There are still constraints in place to ensure the safety of the kernel, but it is far more robust than the classic BPF implementation. eBPF enables a much wider variety of use cases ranging from high-performance networking to system observability, storage troubleshooting, and more. It retains all of the advantages of the original idea behind BPF; it makes the kernel more programmable without the inherent performance penalties, instability, and insecurity of other approaches. However, it does so with a greatly expanded set of tools, resources, and instructions, which makes it applicable to a much wider set of use cases.

You’d be forgiven for being confused about the difference between eBPF and BPF when referring to the current state of the art. Indeed, eBPF’s most prominent advocates like Brendan Gregg have been trying hard to clarify this:

“It’s eBPF but really just BPF, which stands for Berkeley Packet Filter, although today it has little to do with Berkeley, packets, or filtering. Thus, BPF should be regarded now as a technology name rather than as an acronym.”

– “Footnote from ‘BPF Performance Tools’ on page 18 by Brendan Gregg

I’ve often seen eBPF and BPF used interchangeably, and in fact, when classic/legacy BPF is meant (which is rare), I’ve seen it described as “cBPF”. So I would recommend you use the same convention. These days, BPF and eBPF are the same; they both refer to BPF in the modern sense, with all of the aforementioned enhancements.

When I think about eBPF, I like to break it down to the following three topic areas. Together, these provide a really valuable set of tools for anyone looking to add functionality on top of an existing Linux kernel.

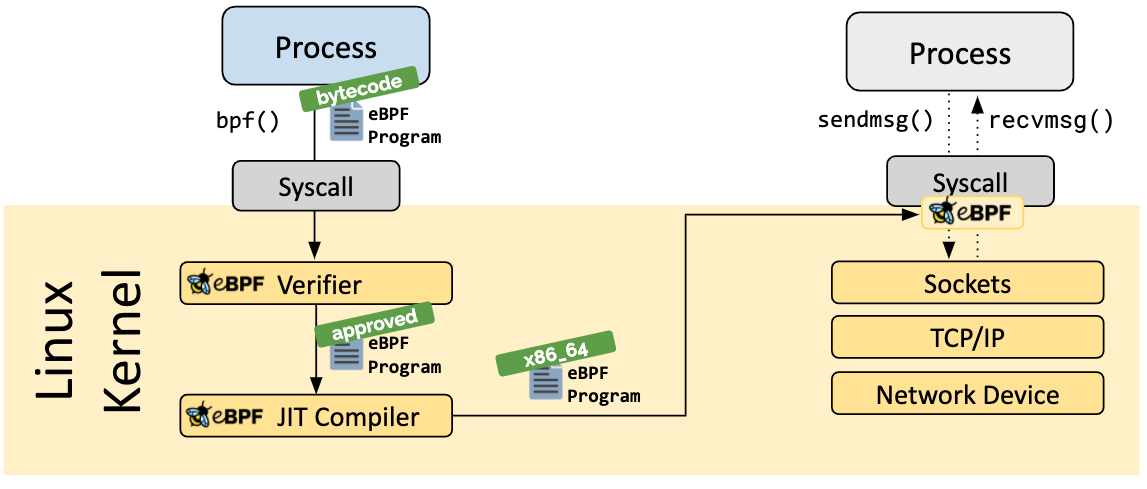

The eBPF Toolchain - these are a series of software utilities (many of which are open source) as well as existing in-kernel components that allow you to write, compile, and deploy eBPF programs that are guaranteed to be as safe and secure as possible.

Probes - specify event-driven rules for triggering a given eBPF program. Just like Javascript programs can react to things like a user clicking a button, eBPF can react to kernel events, and fire custom programs to respond to them quickly, and without involving a userspace process at all.

Maps - share data between kernel and user space safely. This provides a place for eBPF programs to store data and get on with the rest of their operations, while userspace programs can access this data in parallel. You can think of it as a sort of in-kernel key/value store that is accessible from both sides of the boundary.

There’s certainly more to talk about with eBPF, and each of these subjects probably warrants multiple blog posts on their own. However, I think this gives the best 10,000’ view of what eBPF allows you to do. Write safe, performant kernel-space programs, run those programs only when needed, and get the relevant data out into userspace so you can do something meaningful with it.

Diving a Bit Deeper

With the high-level out of the way, I’d like to dive a little deeper into exactly what’s going on with BPF programs themselves. I’m planning to address some of the other topics like the toolchain, and the various other resources available to a BPF program in other posts. These are crucial things to know to understand the full value of eBPF, but for now, let’s just focus on what exactly BPF programs are.

The number one link to bookmark when learning eBPF is ebpf.io. However, if you are interested in more of the “in the weeds” aspects of eBPF, you’ll quickly discover the link to the eBPF and XDP Reference within the documentation for Cilium.

Cilium is an open-source networking and security platform for Kubernetes that is powered by eBPF, and it just so happens I’m using this as the primary CNI in the cluster that powers NRE Labs. It’s one of the most prominent eBPF-powered platforms out there, so a lot of their documentation is also good reading for learning eBPF, and related technologies like XDP which I’ll cover in a future post.

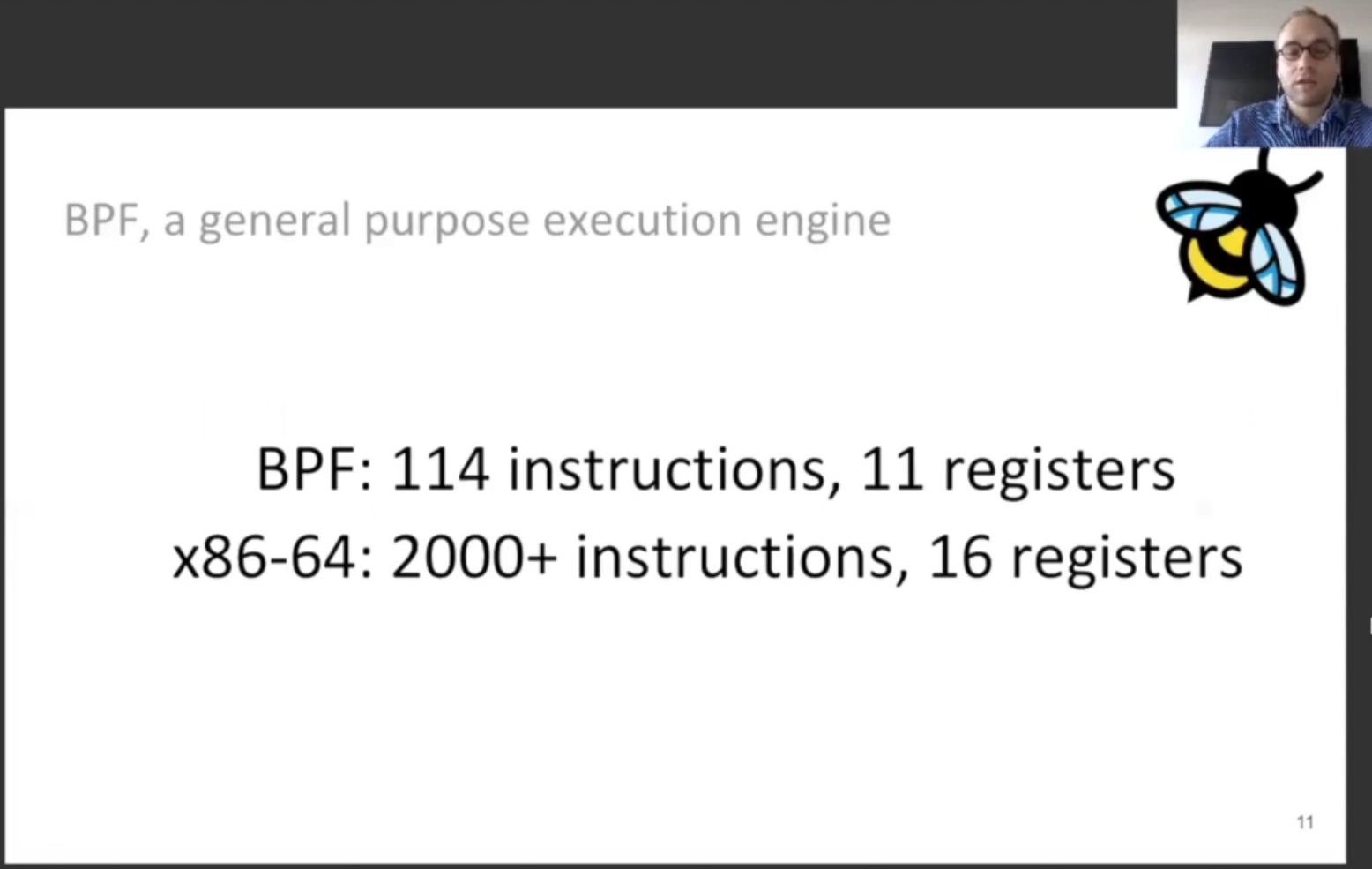

At its core, BPF can be thought of as a simplified general-purpose instruction set. It is similar to something like the x86 instruction set in that it is a series of instructions and registers that can be used to execute programs. However, it is highly simplified. How simplified, you ask?

So, BPF is sort of a “general-purpose execution engine”, but not quite a fully generic instruction set (when compared to something like x86_64). It is highly constrained and simplified to maintain the promise of safe and stable code within the kernel (this is in addition to a series of other verifications that take place at a higher level).

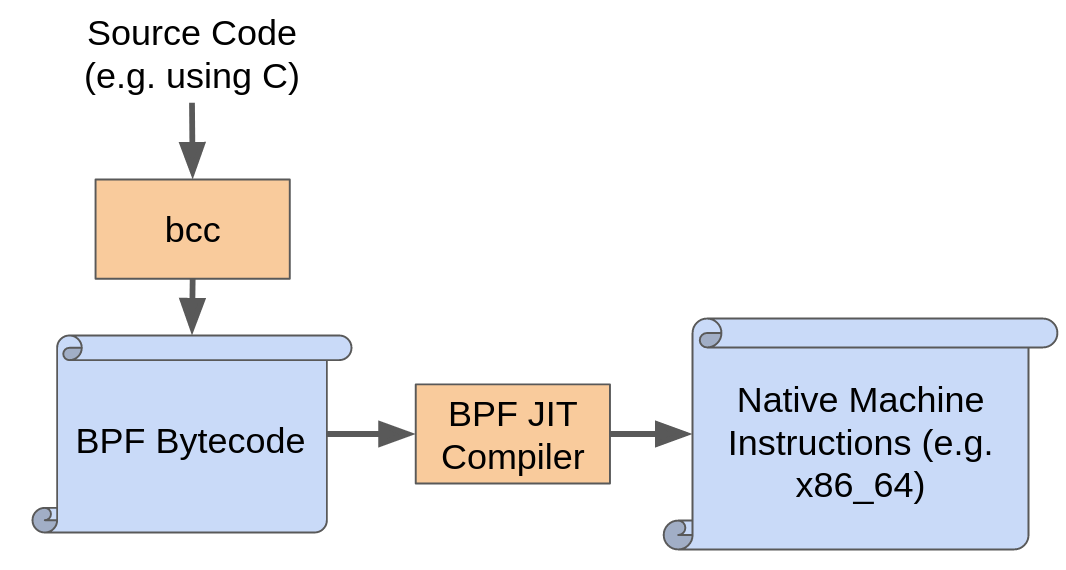

However, there are two other pieces to be aware of that makes this part of the BPF story really powerful. First, you are not required to write BPF programs from scratch by slinging opcodes yourself. There exist plenty of tools that can take higher-level languages, and compile them down into BPF bytecode. bcc allows you to write BPF programs in C, and even front-end those programs using high-level languages like Python. There are other libraries in Go and Rust (which we’ll explore in a future post) that give you a lot of flexibility in working with BPF. So, in terms of writing BPF programs, you have a lot of options.

The other thing to consider is that once a BPF program is compiled into BPF bytecode, it needs to be executed. Of course, the processor in your computer doesn’t know how to speak BPF, so at some point, this needs to be translated to native machine instructions. This is the purpose of the “JIT compiler”. Because of this, the BPF program can perform just as well as any other code running in the kernel (including modules), but with the added benefit of having gone through a pipeline of tools that ensure it is safe.

So, while there are a lot more components that play a role in getting a BPF program from inception to execution, it generally flows through these three states: source code, then BPF bytecode, and finally, native machine instructions.

Who Cares?

If you’re not a kernel developer (statistically speaking, most of you), you may be asking why you should care about eBPF. This is a valid concern, but I’d like to raise a few important points.

I think a takeaway for the average infrastructure operator is that eBPF is one of those technologies that has significant trickle-down effects for your operations. You should care about the role eBPF plays in your infrastructure software in the same way you should care about where your food comes from. You don’t have to be a farmer to have a vested interest in knowing more about that supply chain and using that knowledge to drive decision-making.

Think about how bugs in Linux are fixed today, and the weeks, months, or sometimes years it takes for those fixes to make their way into your shop. Bugs like these have to get fixed in the kernel, which then has to get released, and then we have to wait for our operating system vendor to release a version of their own that uses this upgraded kernel (which for some vendors can take a long time). Once that’s all done, we then have to actually upgrade the thing, which has all kinds of operational considerations (2 AM Saturday maintenance windows anyone?).

This kind of operational pain is felt equally by sysadmins who are deeply familiar with the distribution running on their server cluster but also to network engineers or storage admins who aren’t aware that their switch or cluster is running Linux under the covers. With BPF, if there’s a bug, this can get fixed in the BPF program itself, and in most cases, upgraded live without bringing anything down, or waiting for a new kernel or operating system release. This is because BPF allows your vendors to insert their own kernel functionality without having to include it in the mainstream kernel, or maintain fragile kernel modules.

eBPF also enables a significant ability to simplify the software that’s running on our systems. Ivan Pepelnjak and Thomas Graf discussed eBPF on an episode of “Software Gone Wild”, and Thomas raised an interesting point:

“The nice thing about using eBPF for container networking is that since you’re creating the forwarding logic as a program on the fly, you can remove a whole lot of complexity because you’re only adding the code that you need. If a container doesn’t need v4, don’t include that logic.”

That said, I do think eBPF is more directly applicable to a software-savvy infrastructure professional when it comes to troubleshooting and observability. Clearly, some platforms like Cilium have been able to leverage eBPF to build full-blown networking solutions, but you don’t have to have that kind of big idea to get some value out of eBPF. You can use eBPF to add a little bit of instrumentation to your system to expose some metrics that are meaningful to you. See tcplife as an example. bpftrace allows you to write very simple BPF programs for tracing and observability very quickly. Having the ability to write some quick tooling for yourself is powerful, and the eBPF tool-chain makes the kernel more accessible for those that just want a quick solution to a problem they’re having.

So, while the vast majority of those reading this post may not need to dive into the deepest weeds of eBPF, I believe it’s important for everyone to be aware of it, understand the problems it solves, and consider this new architecture when making technology decisions going forward. I like to explain it like this: even network operators who have never designed an ASIC before are still expected to know at least a little bit about how they work; it only aids in their understanding of the networks they manage. Minimally, I view eBPF the same way. So, whether you’re rack-mounting switches or allocating memory on the heap, eBPF will be a part of your supply chain, and you owe it to yourself to be informed. This is really about making the kernel programmable - which is such a fundamental change, I think we’ll be experiencing the repercussions on this for years to come.

Conclusion

Honestly, I’m excited to dig into eBPF. The architecture is very pleasing to me, not only because of the speed and safety aspects but because event-driven architectures have been a part of my upbringing for a while and it’s the way my brain works. eBPF also happens to be spiritually aligned with what I’ve come to appreciate from other technologies like the Rust compiler, which goes a long way (sometimes painfully) to ensure your software is safe while still keeping performance as high as possible.

I’ll be following up with some posts focused on some specifics, but hopefully, this suffices as a high-level introduction to eBPF and the problems it aims to solve.

Additional Resources

Some other super useful resources I didn’t link to above:

- eBPF Summit Videos (I learned a LOT watching these videos)

- eBPF - a new type of software - Brendan Gregg

- BPF at Facebook - Alexei Starovoitov

- eBPF Superpowers - Liz Rice

- Github collection of awesome eBPF resources

- LWN - a thorough introduction to eBPF

- A Brief Introduction to XDP and eBPF

- BPF, eBPF, XDP and Bpfilter… What are These Things and What do They Mean for the Enterprise?