Polymorphism in Rust

June 22, 2021 in Programming15 minutes

In the previous post we explored the use of generic types in Rust and some of the common reasons for doing so. In this post, I’d like to take a step back and look at the full spectrum of options Rust makes available for accomplishing polymorphism, and get under the covers so we fully understand the tradeoffs of the decisions we make as Rust developers.

Rust’s Polymorphic Choice

If you’re reading this post, you’ve almost certainly heard of the term “polymorphism”. In my own words, polymorphism gives us the ability to present a single interface for potentially many different concrete types. This allows us to create more flexible APIs which give more control to the consumer and are easier to maintain.

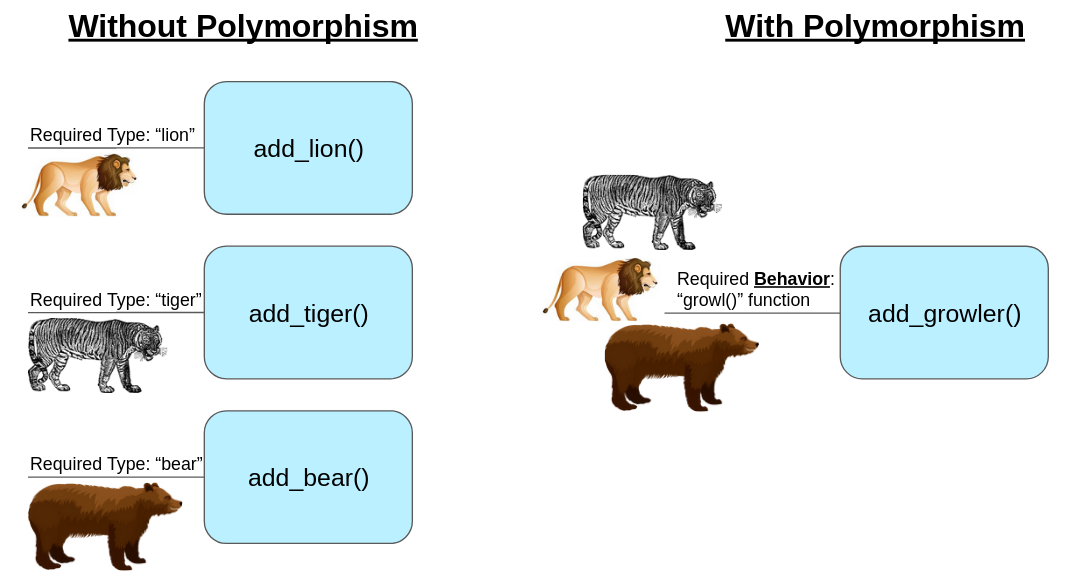

There are several practical advantages to using polymorphism, but one of the biggest is code re-use. If you design an API around specific, concrete types, then you’re committed to that approach, and so are your consumers.

As an example - if we wrote a function that requires a type - Lion as a parameter, we’re bound to that decision strictly. If we wanted to have similar functionality, but for other types, we’d have to create additional functions to accept those types. This results in a lot of unnecessarily duplicate code, which becomes difficult to maintain.

Instead, polymorphism allows us to create functions that accept any type, as long as those types exhibit certain behaviors or properties that we need them to have. In this example, we can accept any concrete type as long as they implement a growl() method.

In this case, that behavior is actually all we care about, so we can leverage polymorphism to be more flexible, but maintain a set of required functionality. Through this, we can do things like write a single function that accepts multiple types.

This is the general idea behind why we would want to use polymorphism in any language, but what options for polymorphism exist in Rust? There are two primary ways, and both of these have trade-offs to consider when it comes to performance as well as binary size:

Static Dispatch - this approach leverages generics (also called parametric polymorphism) and (usually) trait bounds to provide the flexibility we need while still maintaining full type safety, and without requiring a lot of duplicate code. This approach is extremely performant (in Rust this is known as a “zero-cost abstraction”) - however, due to monomorphization, this does create a larger binary size.

Dynamic Dispatch - this approach uses “trait objects” to punt the decision of which type is required to satisfy some kind of polymorphic interface to runtime. This cuts down on binary size (as no monomorphization is used here) but incurs a performance penalty due to the extra lookup at runtime. This approach also explicitly forbids the use of generics.

While there are other reasons to pick one approach or the other - such as readability - in general, you can think of this decision as a trade-off between binary size and performance. If you can tolerate a slightly larger binary size but performance is important, the static approach is probably your best bet. For others who don’t need maximum performance but binary size is critical (embedded systems would be a likely example), the dynamic approach is likely preferable.

What’s more interesting to me personally is that Rust is the first language I’ve used that gives this choice. Languages that don’t have generics force the developer to either write a bunch of duplicate code to get the benefits of the “static” approach, or take the performance hit caused by the “dynamic” approach. I know there are other languages that give this choice (C++ is one of them), but the way this is done in Rust is really nice.

It is this choice that I want to drill into more deeply.

EDIT: A very helpful redditor pointed out a few things to keep in mind when reading this blog post. The examples to follow were made by disabling inlining and building in “debug” mode, to make the learning experience a bit easier, but I didn’t do a good job of highlighting this choice. Building in release mode and allowing Rust to inline where needed will likely change the resulting program significantly.

The “Growler” Trait and Its Implementations

For this post, I’ve created a trait called Growler which enforces a single method implementation growl() which has no parameters or return types. I’ve also created three types Lion, Tiger, and Bear which have their own implementations of this trait. We will be using these three types to demonstrate the difference between static and dynamic dispatch:

trait Growler {

fn growl(&self);

}

struct Lion;

impl Growler for Lion {

#[inline(never)]

fn growl(&self) {

println!("Lion says GROWL!");

}

}

struct Tiger;

impl Growler for Tiger {

#[inline(never)]

fn growl(&self) {

println!("Tiger says GROWL!");

}

}

struct Bear;

impl Growler for Bear {

#[inline(never)]

fn growl(&self) {

println!("Bear says GROWL!");

}

}Regardless of the method we explore below (static and dynamic), this code will remain the same. The difference between static or dynamic dispatch isn’t found in the declaration of this trait, or the types and methods that implement it, but how we use them in our Rust code, and more importantly how the two approaches actually work under the hood in our compiled program.

Static Dispatch

As a refresher on generics in rust, we can leverage generics in a few places. When defining a function, we can define a generic type in the function signature, and then reference that type for one of the parameters:

fn static_dispatch<T: Growler>(t: T) {

t.growl();

}As we learned previously, by defining the Growler trait as a bound on the generic parameter T, whatever type that’s passed in must implement that trait. So, in our main() function we can pass in our three concrete types, which we know all implement this trait:

pub fn main() {

static_dispatch(Lion{});

static_dispatch(Tiger{});

static_dispatch(Bear{});

}This approach leverages the “static dispatch” approach, which makes use of “monomorphization” during compilation time to create multiple copies of our static_dispatch function - one for every type that’s ever passed into it. This is the more efficient approach, since we can essentially bake in all our execution paths into the resulting program, without having to calculate this at runtime.

We can immediately see the signs of monomorphization by using objdump to look at the instructions present in our compiled Rust program:

objdump --disassemble=polymorphism::main -S -C target/debug/polymorphism -EL -M intel --insn-width=8

target/debug/polymorphism: file format elf64-x86-64

0000000000005510 <polymorphism::main>:

5510: 48 83 ec 18 sub rsp,0x18

5514: e8 47 fe ff ff call 5360 <polymorphism::static_dispatch>

5519: e8 12 fe ff ff call 5330 <polymorphism::static_dispatch>

551e: e8 6d fe ff ff call 5390 <polymorphism::static_dispatch>Our static_dispatch function has no parameters, and calling it is the first thing we do in our main() function, so the very first thing we see are three calls to the location of this function in memory. However, you’ll note that all three locations are different - 5360, 5330, and 5390. This is because they are actually three different functions - one for each of our concrete types.

0000000000005330 <polymorphism::static_dispatch>:

5330: 48 83 ec 18 sub rsp,0x18

5334: 48 89 e7 mov rdi,rsp

5337: e8 34 01 00 00 call 5470 <<polymorphism::Tiger as polymorphism::Growler>::growl>

...

0000000000005360 <polymorphism::static_dispatch>:

5360: 48 83 ec 18 sub rsp,0x18

5364: 48 89 e7 mov rdi,rsp

5367: e8 b4 00 00 00 call 5420 <<polymorphism::Lion as polymorphism::Growler>::growl>

...

0000000000005390 <polymorphism::static_dispatch>:

5390: 48 83 ec 18 sub rsp,0x18

5394: 48 89 e7 mov rdi,rsp

5397: e8 24 01 00 00 call 54c0 <<polymorphism::Bear as polymorphism::Growler>::growl>

...The compiler took our single static_dispatch function in Rust, and during compilation, created one instance for every concrete type that’s ever passed to it. Then, within each of these functions, it bakes in the call to the relevant method implementation, which is why you see a call to the three different types’ growl() method in each.

It should now be obvious why the “static dispatch” approach results in a larger binary size - the compiler is able to perform all these pre-optimizations, but must store all the monomorphized code in the binary itself. However, our program is more efficient, since the decisions of which functions to call based on which types is all done at compile-time, not run-time. The Rust code we have to maintain is still as elegant and concise as we want.

By the way, this approach is not impacted at all performance-wise by the presence of a trait bound (in fact, the resulting compiled program is identical). This is still a zero-cost abstraction - the only difference is that the addition of trait bounds add compile-time checks for which concrete types can be used as a parameter to our function. If we were to pass in a type that didn’t implement the

Growlertrait, our code would simply not compile.

This is the core of what makes this “static” approach to polymorphism so powerful. We write concise code, and the compiler takes care of the rest to ensure that performance remains high.

Dynamic Dispatch

Dynamic dispatch can be characterized as the opposite of static dispatch. Where static dispatch choses to create copies of all functions that use generic parameters and store these in the binary, dynamic dispatch choses to store only a single copy, but then calculates the necessary concrete implementation at runtime.

In Rust, this approach leverages “Trait Objects” to achieve polymorphism. Unlike trait bounds, which is an optional constraint you can add to generic parameters, trait objects actually cannot be used with generics at all, and instead are the required method for performing dynamic dispatch in Rust.

The syntax for trait objects these days is characterized by the dyn keyword, followed by the name of a Trait:

fn dynamic_dispatch(t: &dyn Growler) {

t.growl();

}The dyn keyword was introduced in Rust 1.27 and is now the idiomatic way to explicitly specify that you wish to use dynamic dispatch through trait objects. While it is still possible to imply the use of trait objects without this keyword at the time of this writing, it is officially deprecated and eventually you will have no option but to use this keyword in a future version of Rust.

Even though we’re not using generic parameters, the compiler still needs a little help to know the size of our types at compile-time. This is why you’ll commonly see trait bounds passed in via reference, as in the example above - but this can also be accomplished by wrapping the trait object in containers like

Box<dyn Growler>,Rc<dyn Growler>orArc<dyn Growler>.

We can then call these from the main function by passing in references to each type:

dynamic_dispatch(&Lion{});

dynamic_dispatch(&Tiger{});

dynamic_dispatch(&Bear{});Let’s take a look under the hood and see what the Rust compiler produced for these calls:

0000000000005510 <polymorphism::main>:

...

# "dynamic_dispatch" call with "Lion" type

#

# Populates "rax" with a pointer to 0x43558

5523: 48 8d 05 2e e0 03 00 lea rax,[rip+0x3e02e] # 43558

552a: 48 8b 0d ef df 03 00 mov rcx,QWORD PTR [rip+0x3dfef] # 43520

5531: 48 89 cf mov rdi,rcx

# Moves pointer in "rax" into "rsi" register

5534: 48 89 c6 mov rsi,rax

5537: e8 44 00 00 00 call 5580 <polymorphism::dynamic_dispatch>

# "dynamic_dispatch" call with "Tiger" type

553c: 48 8d 05 35 e0 03 00 lea rax,[rip+0x3e035] # 43578

5543: 48 8b 0d d6 df 03 00 mov rcx,QWORD PTR [rip+0x3dfd6] # 43520

554a: 48 89 cf mov rdi,rcx

554d: 48 89 c6 mov rsi,rax

5550: e8 2b 00 00 00 call 5580 <polymorphism::dynamic_dispatch>

# "dynamic_dispatch" call with "Bear" type

5555: 48 8d 05 3c e0 03 00 lea rax,[rip+0x3e03c] # 43598

555c: 48 8b 0d bd df 03 00 mov rcx,QWORD PTR [rip+0x3dfbd] # 43520

5563: 48 89 cf mov rdi,rcx

5566: 48 89 c6 mov rsi,rax

5569: e8 12 00 00 00 call 5580 <polymorphism::dynamic_dispatch>

...I’ve added some spacing above to make it easier to follow. In short, each section is responsible for making some calculations prior to calling the dynamic_dispatch function, which will ultimately be used to determine which underlying concrete type and method is used.

- The most important calculation is performed by the first instruction in each section, which loads a pointer (

leainstruction) into theraxregister. For example, the “Lion” section loads the location resulting from addingrip + 0x3e02e. Fortunately, the compiler gave us a helpful hint of what this results in -0x43558(shown as a comment to the right). The Tiger section loads0x43578, and the Bear section loads0x43598. We’ll get into what these values mean in a little bit. - Then, on the fourth line, the contents of the

raxregister (which contains the result of the first instruction) are copied intorsi. - Finally, on the final line of each section, you can see a call to the location 5580 - our

dynamic_dispatchfunction. All three sections call the same location - this is a stark contrast to what we saw in the static dispatch section, where each call was to a different memory location. This is a strong early clue that no monomorphization was used here!

Next, lets take a look at our dynamic_dispatch function. Unlike the section where we discussed static dispatch and “monomorphization”, we only find a single copy of this function in the compiled program:

0000000000005580 <polymorphism::dynamic_dispatch>:

fn dynamic_dispatch(t: &dyn Growler) {

5580: 48 83 ec 18 sub rsp,0x18

5584: 48 89 7c 24 08 mov QWORD PTR [rsp+0x8],rdi

5589: 48 89 74 24 10 mov QWORD PTR [rsp+0x10],rsi

# This is where the concrete type's method is called

558e: ff 56 18 call QWORD PTR [rsi+0x18]

...The reason our dynamic_dispatch function is able to appear once in the compiled program is because it’s designed to call a function at a calculated location, specifically an offset based on whatever value is in the rsi register. This is why our program does the hard work of calculating a pointer to the right location in memory, and placing it in rsi up front, before the dynamic_dispatch function is called.

So we know from the previous example that rsi will contain 0x43558 when our Lion type is used, 0x43578 for Tiger, and 0x43598 for Bear. But what do these values actually mean? And why is the program adding 0x18 to this value before calling the resulting memory location?

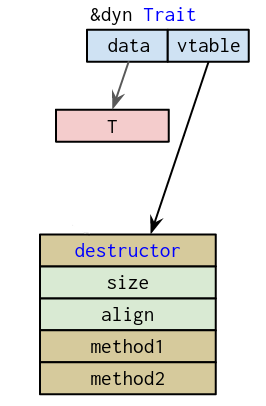

This gets us to the core of what a trait object actually is. In short, it’s a pointer. Specifically, it’s a pointer to portion of memory where a type’s bound methods can be found, as well as a few other things (like destructors). This is commonly referred to as a “virtual method table”, or “vtable”.

Each concrete type with methods has a vtable created and stored in memory that can be accessed by our program when it’s time to figure out where a given method is for a given type. You can think of it as a directory for all of the concrete types and their methods.

Each of the three memory locations loaded into rsi throughout the lifetime of our program is the location where a different type’s vtable is located:

Unfortunately I had some issues finding the vtable in

objdumpoutput - for some reason what I found at the referenced offset was totally different from what other tools were showing me, and I couldn’t figure out why. So, the text below is copied from a really cool visual disassembler called Cutter.

0x00043558 .qword 0x00000000000052b0 ; sym.core::ptr::drop_in_place::h1a84c45b0db95228 ; dbg.drop_in_place_polymorphism::Lion; RELOC 64

0x00043560 .qword 0x0000000000000000

0x00043568 .qword 0x0000000000000001

0x00043570 .qword 0x0000000000005420 ; sym._polymorphism::Lion_as_polymorphism::Growler_::growl::h9ba07c281cda2327; RELOC 64

0x00043578 .qword 0x00000000000052d0 ; sym.core::ptr::drop_in_place::hbe44f9f0e5cd7b58 ; dbg.drop_in_place_polymorphism::Tiger; RELOC 64

0x00043580 .qword 0x0000000000000000

0x00043588 .qword 0x0000000000000001

0x00043590 .qword 0x0000000000005470 ; sym._polymorphism::Tiger_as_polymorphism::Growler_::growl::hd8d4c2f459b86277; RELOC 64

0x00043598 .qword 0x00000000000052c0 ; sym.core::ptr::drop_in_place::h5b23dc3563c0609b ; dbg.drop_in_place_polymorphism::Bear; RELOC 64

0x000435a0 .qword 0x0000000000000000

0x000435a8 .qword 0x0000000000000001

0x000435b0 .qword 0x00000000000054c0 ; sym._polymorphism::Bear_as_polymorphism::Growler_::growl::h4af959d647eb2439 ; dbg.growl; RELOC 64 Again, I added some spacing to make it easier to follow. You’ll note that each of the three memory locations loaded into rsi mark the beginning of each type’s vtable in memory. However, the portion of the vtable that contains a pointer to the method we wish to call is actually located at an offset of 24 bytes from the beginning of each table. Incidentally, the hexidecimal equivalent for this is 0x18, which is why our dynamic_dispatch function adds this to rsi before the call instruction. rsi contains the location of the vtable for the type we want, and adding 0x18 to this gets us to the entry in this vtable that we want to access.

However, what’s located here is still not our method, but rather another pointer. For example, the memory location 0x43570 just contains a pointer to 0x5420. It is this location where we can find our method. This is why the dynamic_dispatch function uses the instruction call QWORD PTR [rsi+0x18] - it first loads the value located at rsi + 0x18 as a pointer, and then calls the memory location represented by that pointer.

If you look closely, each of these pointers should look familiar - 5420, 5470, 54c0. These are the same addresses where we saw the methods for each type back in the static dispatch section! Regardless of whether we’re using static or dynamic dispatch, these functions still need to exist in our program - the difference is how we access them.

As you can see, dynamic dispatch takes the opposite approach when compared to static dispatch. Instead of duplicating polymorphic functions based on the types that are used, a single implementation is created, but that implementation is designed to call different underlying types and methods based on a pointer that is calculated at runtime. Due to the lack of code duplication, the binary size is smaller, but because of the additional lookup that needs to take place, there’s a small performance hit. I’ll leave the analysis of this performance hit to others - there are plenty of blog posts out there that do a much better job of benchmarking dynamic dispatch than I ever will.

Conclusion

This was a fun blog post to write, and it gave me a much better understanding not only of Rust’s polymorphism options, but also a better understanding of how other languages offer similar tradeoffs. I hope it was useful for you as well.

I created a project in Compiler Explorer which contains the full program with both approaches. This is an excellent tool which makes it very easy to see how our program actually works under the hood, so if you don’t feel like using objdump or Cutter, this is a great learning tool as well.

Additional Links

Some additional links I found in my research that didn’t make it into the body of this post:

- Very useful and instructive Compiler Explorer example; was inspired to create my own from this.

- Helpful SO thread where trait object containers and vtables are discussed

- Another useful post on how this is done in Rust with some cool Cutter graph diagrams