Difference between 'iter()' and 'into_iter()' in Rust

February 6, 2026 in Rust3 minutes

In today’s edition of “things that really confused me when starting with Rust” - I struggled to understand the difference between these two methods I kept seeing:

into_iter()iter()

You can often find both methods on commonly used Rust types, like Vec, and in this case they appear to do the exact same thing.

What’s the difference? Why does Rust give us a choice here? In this post I aim to disambiguate the two so that this can be a bit clearer.

into_iter()

into_iter() comes from the IntoIterator trait, which allows you to define how your type returns an iterator.

This is what gives the ability to iterate natively over a type with Rust’s for syntax. You don’t need to invoke into_iter() explicitly - so:

is identical to:

The return type for into_iterator() is another trait: Iterator - the iterator itself

(has a next() method).

Both of these traits have an associated type Item which defines the type which is returned by every

iteration - in other words, the type contained by the collection we’re iterating over. For the above example, we’re iterating over Vec<i32> so the associated type Item would be i32.

As we discovered in a previous blog, not only the type, but the way in which you’re working with that type wrt Rust’s three ownership cases

determines the implementation used when invoking into_iter(). Iterating over a Vec<&T> may be very differerent from Vec<T>.

So in summary, into_iter() is the required method of the IntoIterator trait, the primary iteration trait used in Rust. The manner in which that iteration takes place is determined by

the type you’re calling it on, and which of the three ways described above

iter()

Even after reading the above, you’d be forgiven for believing that if into_iter() is the required method for IntoIterator, perhaps iter() is the primary method for the Iter trait.

Indeed this was a huge point of confusion for me early on.

In fact, the iter() method is actually not a trait method at all, but rather a convention established by the Rust API Guidelines, and used throughout the standard library. Generally it’s a way to

get access to an iterator over references for whatever type it’s defined on. This is in contrast to IntoIterator which can be implemented by T, &T, or &mut T at will.

So, the convention, simply put, is implemented on T in order to return an iterator that returns only &T.

Iterate over Mutable References

Similarly, the sibling method (also just an agreed-upon convention) iter_mut() does the same thing for only &mut T.

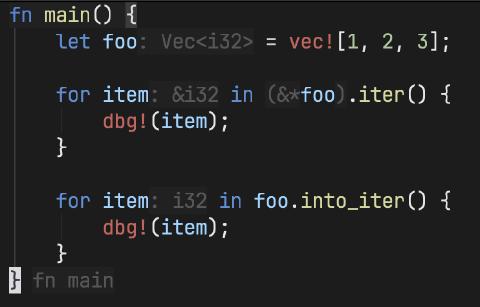

If you have an editor with LSP integration and inlay type hints turned on, we can compare the usage of iter() alongside into_iter() to see this is the case:

Even though the above code is iterating over the Vec by value, only references are being moved, so the following consuming iterator from into_iter() can still work.

This convention is used by many types in the standard library, including collections like Vec, maps like HashMap, arrays, slices, even String (though you’d probably use something like chars() or bytes() in this case).

In the case of a Vec, iter() simply returns Iter. You’ll notice this is defined

on std::slice, which gives away what Vec’s .iter() actually isn’t Vec’s; it belongs to the Vec’s underlying slice. This is because Vec implements

“deref coercion” so it automatically exposes all the underlying slice’s methods.